‘Face to Face’ is an apt title for this comprehensive survey of the work of Lotte Laserstein (1889–1993). Throughout her life, Laserstein was preoccupied with the enigma and confrontation of the returned stare, her own emerging as the most constant and profound of all. It is the portraits, specifically the self-portraits in which Laserstein’s dark eyes look back at us under hooded lids, with an almost haughty upward tilt of her top lip, that make an indelible impression. A ‘face-to-face’ suggests a deeper level of communication and, with this on offer, we have an obligation to return the gaze squarely, with eyes and mind open.

The vivid portraits of the new women and modern men of the Weimar Era for which she is celebrated are carefully complemented in this show (which has travelled from the Städel Museum) with landscapes and later works made after Laserstein emigrated to Sweden in 1937. If these works lack the edge of those from the Berlin years, they reflect how, in enduring the mental schism of forced exile, her relationship to her talent became complicated. She took on commissions to earn a living, but in 1946 felt ‘wretched that after nine years in Sweden one is no further on than at the beginning’. Gothenburg Harbour (1943), a nocturne drawing inspiration from Old Masters as much as lens-based innovations of the age, enriches our understanding of what Laserstein could do with paint, but the later works also question the idea that suffering begets ‘great art’. Classified ‘three quarters Jewish’ under the Nazi dictatorship, Laserstein had been banned from participating in German cultural life after 1933. In 1943, she learned that her mother had been murdered at Ravensbrück concentration camp.

Evening over Potsdam (1930), Lotte Laserstein. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie. VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2019

Laserstein’s bravura skill as a draughtswoman reaches its peak in her masterpiece Evening Over Potsdam (1930). Here, the looming political nightmare seems to descend over a group of weary moderns engaged in a secular version of The Last Supper. This skill was, perhaps, a sort of albatross in the era of the ‘New Objectivity’, with contemporaries such as Christian Schad and Jeanne Mammen pursuing a more obviously avant-garde agenda. But how might she have warped her line to greater effect? What did it mean to possess such pure illustrative technique, when everything about your identity could be deemed ‘warped’?

The exhibition texts avoid comment on Laserstein’s sexuality, erring towards the idea that ‘if anything, it is painting itself that comes across as the erotic act for Laserstein’. As a queer viewer, it is not that you demand an absolute position on the artist’s sexuality, rather that the conversation shouldn’t always lean towards a heteronormative viewpoint; one that regularly assumes the potential sexual relationship between a male artist and his muse, but ignores or neutralises what is on display here. Laserstein’s portraits of her ‘friend’ Traute Rose are laced with same-sex intimacy. It is widely agreed that Laserstein’s great power is her ability to communicate psychological states between characters or, indeed, the characters and ourselves. It therefore seems odd, blind even, to turn away from Laserstein’s sexuality.

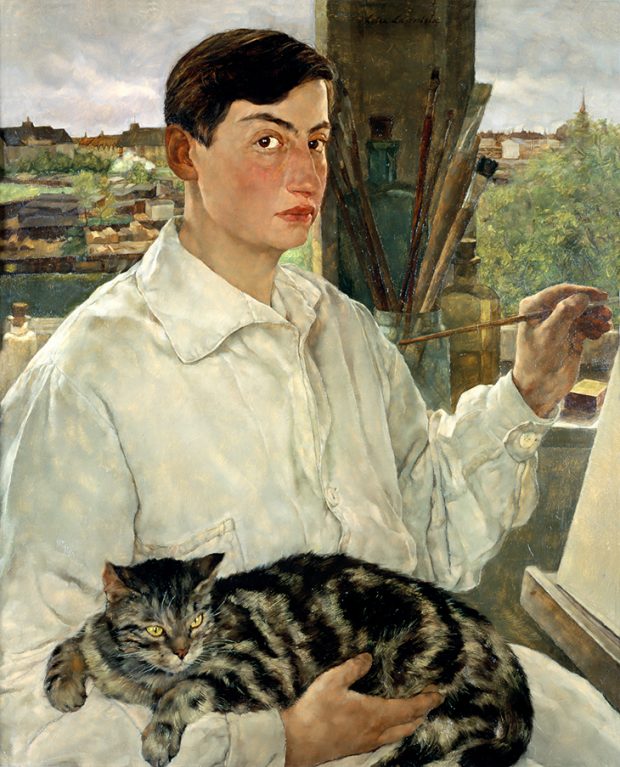

Self-Portrait with a Cat (1928), Lotte Laserstein. New Walk Museum and Art Gallery, Leicester. © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2019

In I and my Model (1929/30), the artist works at her easel, her face turned to confront the viewer, her eyebrows arched knowingly. Traute, not classically nude, but in a domestic state of undress, observes close behind, her hand on Laserstein’s shoulder where a patch of light beneath electrifies the gesture. It is a radical take on the gendered power-play of the artist and model, feminist in its depiction of care and interdependence, while glinting with delight and provocation. Its erotic charge is picked up in a series of quick, tender sketches of Traute sleeping naked in bed, executed on pages from a small sketchpad that might have been kept by the bedside and reached for upon waking. In the At the Mirror (1930/31), the naked Traute grapples with a mirror. Her back is to the viewer, so that her reflected stare is the only clearly visible face in a composition that hints at The Three Graces. Traute meets her own determined, sensual expression as Laserstein stands braced in front of her easel in a dingy workman’s coat, energetically squeezing paint on to her palette. Traute, the mirror, and the edge of Laserstein’s canvas as it slices back into the picture plane, are luminous elements in the painting, framing Laserstein, as she so often depicted herself, at work.

At the Mirror (1930/31), Lotte Laserstein. The Bute Collection, Mount Stuart.

‘Lotte Laserstein: Face to Face’ is at the Berlinische Galerie, Berlin, until 12 August.