A sculpture’s presence can’t be measured by its weight. Down in the darkened basement gallery of Sprüth Magers in London, Anthony McCall has installed Meeting You Halfway II, a recent example of his ‘solid light works’. It consists of two partial ellipses, projected onto a wall; they expand and contract slowly, at different rates and in different proportions, and they occasionally, but rarely, meet. The basement is filled with haze, artificially produced, and this makes the projected light visible in the air, drifting silently up and down over the ambient thrum of the room. The wide, curving sheets of light – McCall calls them ‘membranes’ – remind me of Richard Serra’s work, those heavy slabs of steel that bend around the space they circumscribe. On the other hand, Meeting You Halfway II isn’t tangible at all. The difference between Serra’s work and his own, McCall suggests wryly, is ‘about 40 tonnes’.

Study for Meeting You Halfway (II) (2016), Anthony McCall. © Anthony McCall; courtesy Sprüth Magers

McCall’s materials have never been solid; since he began in the 1970s, he’s worked in light, fire and smoke. Their ‘three-dimensional form’, as he calls it, derives not from their weight but from ours. Even a sculpture of light ‘requires the human body to move around it in order to understand it’. It takes our presence to give that work a presence of its own. Not that McCall expects any one thing, or several things, from his spectators; they’re free to walk through the membranes, move about, turn from wall to wall, watch the projection from inside. Nor does he give them the hook of a plot. His earliest projects had basic narratives, in contrast to the bulk of his ‘light works’ since then. Line Describing a Cone (1973), for instance, was his first major piece. It began with a single dot on a black wall, which moved through an arc, then a semi-circle, into a full circle; when it was finished, the ‘volumetric form’ of a light-cone was complete. It was, says McCall, ‘in a way, a narrative film – it announced its intention at the beginning, and it realised it by the end’.

This neatness began to frustrate him, though his audience wasn’t helping. At the same time (between 1972 and 1974) he produced the ‘fire works’; these were installations in rural fields, comprised of small fires arranged in grids, which were lit and extinguished at intervals according to a pre-planned ‘score’. They’re represented not at Sprüth Magers, but in McCall’s larger exhibition at the Hepworth Wakefield. Landscape for Fire II (1972) is a 16mm film, made with a handheld camera, capturing a one-off performance; it has the shaky, excited quality of someone present at a twilight ritual. The problem, for McCall, was that excitement and anticipation were closely twinned. ‘People would come with an expectation that could never be met. Some people came expecting something like a firework display.’ He adds, again a little wryly: ‘they could only be disappointed.’

Landscape for Fire II (film still; 1972), Anthony McCall.

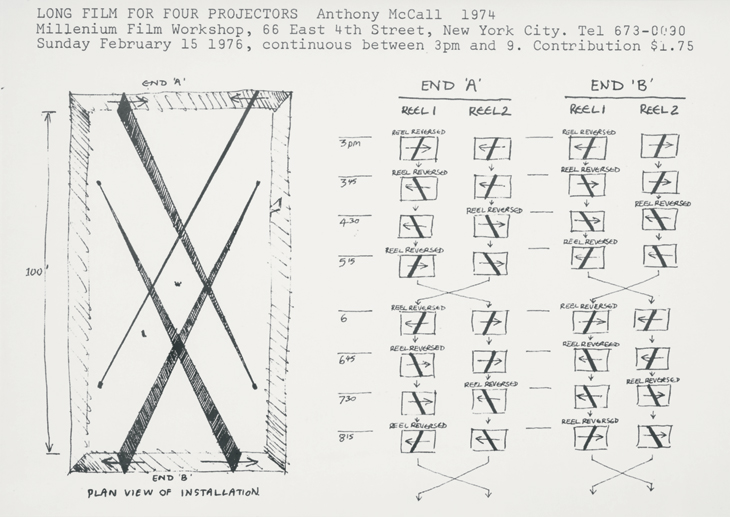

McCall began to think of an audience, considered as a unified entity, as something entropic: ‘a construct that doesn’t last very long’. So, abandoning the linear narrative of Line Describing a Cone, he began to extend the duration of his pieces, and pick apart that frustrating ‘construct’. His next work was Long Film for Four Projectors (1974). As the studies on display at the Hepworth show, it was implausible that a uniform group of people might stick around to experience the work together; the film was five-and-a-half hours long, and while its four planes of light swept slowly through each other, moving at different speeds and angles from opposite sides of the room, all the sculptural relationships between them were continually transformed into new configurations. The sculpture became a process. ‘What I had in mind’, McCall explains, ‘was the removal of that entity called the “audience”, and the introduction of a new entity called the “visitor”’. The scheduled film became a distended ‘installation’. ‘They come, and they go.’

Announcement for Long Film for Four Projectors (1974), at Millennium Film Workshop, 1976. Courtesy Anthony McCall

The trouble with people, though, is the way they worry about each other. McCall admits that there’s a ‘social’ element to his light works. Their space is never entirely dark, even outside the membranes, because those sheets give off a silvery glow; as the visitors come and go, one thing they’ll consistently notice is the other visitors going and coming. My pleasures in Meeting You Halfway II may not be yours, but we see each other taste them – whether it’s looking serious and critical, or dabbing a finger through the light, or crouching down for the childishly satisfying point at which the projected ellipses meet and their projections come together. (I saw people at the Sprüth Magers opening do all of these things, and always with a frisson of self-consciousness about them.)

Smoke Screen II (2017), Anthony McCall. © Anthony McCall; courtesy Sprüth Magers

The ‘social’ question is the open-ended one hanging around McCall’s work and your attempts to get lost in its beauty. The most intricate part of a solid light work isn’t its sculptural form, but its surface detail: the whorls and curls of the haze, spinning slowly as it bears up the beams. At both the Hepworth and Sprüth Magers, McCall has photographed these effects, producing gorgeous silver gelatin prints. They reward close inspection, like gazing at a Hubble image of Jupiter’s atmosphere. Their rolling haze was, in McCall’s 1970s light works, produced by his fellow artists’ cigarettes, but now it’s something finer and more manipulable, allowing him to craft imaginary meteorologies. The prints can be contemplated at length, but down in the basement, you can’t fix their protean shape in quite the same way. You see a gently twisting loop, and you follow its motion, then you catch someone watching behind; you’re dragged out of reverie, back to the room everyone shares. What’s the purpose of that return? Do we learn something from it? McCall pauses, for a long moment, then laughs. ‘I think you learn something about being in installations.’

‘Anthony McCall: Solid Light Works’ is at Hepworth Wakefield, until 3 June; ‘Anthony McCall’ is at Sprüth Magers, London, until 31 March.