From the March 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Laure Prouvost has two modes of conducting interviews. One is to offer straight answers. The other is to recount fantastical stories about, say, her fictional grandmother’s fondness for naked skydiving. For better or worse, I get the former approach: I don’t know whether to be disappointed or relieved.

We’re sitting in the cafe of the De Pont Museum of Contemporary Art in Tilburg, the Netherlands, where Prouvost is installing her exhibition ‘In The Mist Of It All, Above Front Tears’ (until 18 August). When I ask about the show, I get a small taste of that surreality: ‘It’s just me standing on top of a French van singing to the cars and the modernist architecture of Tilburg.’ There could not be a greater contrast between De Pont’s cool, industrial white cube and Prouvost’s gloriously messy, inchoate work, which ranges across installation, sculpture and video.

Here, the visitor will enter through ‘a valley of the mess of human production’, walking past a pool of petrol – ‘consumerism spilling out, the leaking world we’ve created’ – then into a billowing cloud created by a smoke machine, where ‘the ceiling will melt down to the floor and birds are hanging around’. There will be sculptures of fish-bird hybrids and a large tent where you can ‘nest’, as she has it, in a pile of beanbags, the shadows of mobiles moving dream-like on the fabric ceiling.

Installation view of Laure Prouvost: Above Front Tears Oui Float at the Nasjonalmuseet, Oslo, in 2022. Photo: David Levene; courtesy Lisson Gallery; © Laure Prouvost

Elsewhere, manmade and natural objects have been bodged together to make hanging composite sculptures that fill several rooms: an ear of wheat conjoined with an iPhone charger; feathers spilling from a cassette tape; a teaspoon sprouting a leaf from its handle. Prouvost gathered this detritus in Molenbeek, the Brussels suburb where the French-born artist lives and works. There is a new focus on the natural world emerging in her practice: at Frieze London last year, Prouvost launched OUI GROW, a charitable initiative that aims to bring more plants to deprived parts of inner-city Brussels.

This nurturing impulse – to foster green spaces or to create places the museum-weary can rest – is a marked tendency in her recent work. Visitors to her website are greeted by a video of the artist whispering reassuring platitudes: ‘I will take care of you, you beautiful thing’; ‘I will hold you straight, make sure you’re in the best place, in the right temperature, next to the right people around, the right pieces around you.’ Though Prouvost is in part poking fun at the veneration of art (she tells me this video is ‘full of bullshit’), I found myself soothed by the hypnotic, ASMR-like qualities of the piece. Her hushed, heavily accented tones float across the mind, as much like thought as speech.

Language – its creation, its uses and its failures – is a subject of ongoing fascination for the polyglot artist. Born in 1978 in Lille, she moved to London as a teenager to study, first at Central Saint Martins and then at Goldsmiths. In her early twenties Prouvost became an assistant to the conceptual artist John Latham, a man she describes as ‘an eccentric grandfather to me’.

Latham’s work often questioned language and structures of knowledge. In 1966, he invited a group of his students to dinner, to ‘eat’ a copy of Clement Greenberg’s Art and Culture, bottling the masticated remnants. There’s something of a familial relationship between Prouvost’s and Latham’s work, with a shared habit of reshaping texts.

Prouvost relishes word play, punning across languages in the titles of artworks, in their content or in the names of her shows. Take her most recent exhibition ‘Oma-je’ at Remai Modern in Saskatoon, which celebrated the artists she considers her forebears, including Latham, Louise Bourgeois, Agnès Varda and Niki de Saint Phalle. That title, ‘Oma-je’, combines the Dutch word for ‘grandmother’ (oma), the French for ‘I’ (je) and the shared Anglo-French ‘homage’.

Though Prouvost shares the preoccupation with language common to Latham’s generation of conceptualists, her approach is lighter at heart. A book accompanying her 2019 exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art Antwerp titled AM-BIG-YOU-US LEGSICON (get it?) is a glossary of Prouvost’s preoccupations: there are entries on boobs, bums, digging, dreams, love, petrol and performance, among others. On language, she writes: ‘Hard to use well […] Helps communication between humans but also misunderstanding.’ On misunderstanding: ‘Feels muddy, opens doors to the imagination.’

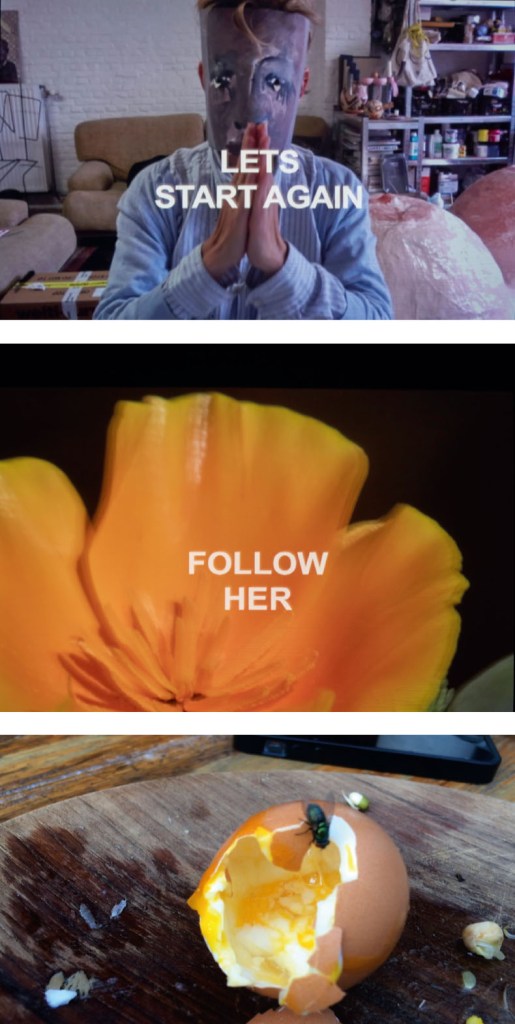

Stills from DIT LEARN (2017), Laure Prouvost. Courtesy Lisson Gallery; © Laure Prouvost

Her film DIT LEARN (2017) – its name a riff on the French dit (‘said’) and the English prefix de-, to undo – feels like a fast-paced language game. The artist plays the part of a teacher, instructing viewers on correct and incorrect terminology. White text on a black ground states: ‘YOU NEED TO LEARN AND REMEMBER THE MEANING OF THINGS.’ A fence post being hammered means ‘no’ and an iguana means ‘yes’; a tangerine means both ‘love’, according to the on-screen text, and ‘press the button’, according to her voiceover. The sequence becomes faster, more frenetic, impossible to ingest.

Prouvost reprised this work in 2020 with the exhibition ‘Re-dit-en-un-in-learning CENTER’, in which Lisson Gallery in London became a mock educational facility, aping the structures that surround formalised learning. (When I ask about the education of her own children, I’m unsurprised to hear that they attend alternative schools.) The films and the exhibition ‘were really about unlearning, playing a kind of a game of reinventing ways of perception’, she says. ‘The exhibition was during Covid times – I wanted us to de-learn to re-learn, to re-imagine the future.’

Her next film took a step further back into childhood development, regressing from the linguistic to the preverbal. Four For See Beauties (2022) was filmed in a sauna in Finland, which was traditionally the place where Finnish women would give birth. A group of naked young women stroke Prouvost’s own baby, crooning semi-nonsensical messages of love and care. They are interspersed and overlaid with footage of sea life – passing fish, the waving arms of starfish, an octopus; everything fleshy, nurturing, intimate. It is a sense-picture of tender infancy.

Stills from Four For See Beauties (2022), Laure Prouvost. Courtesy Lisson Gallery; © Laure Prouvost

‘The focus was to almost delete language […] to go into the depth of the subconscious. The hands are like animals, just feeling,’ she says. ‘Now in the show here [at Tilburg] it’s much more connected to animal life […] how to have empathy with other beings. It’s from de-learning, to pre-language, to becoming other.’

For Prouvost, the bridge between the worlds of language and of bodies is the octopus. Her Legsicon defines ‘Octopus (feminine; noun)’ as a creature that ‘Feels through its leg (brain in the leg)’ and as ‘Brain on the plate’. The cephalopod recurs throughout her work, whether in real, dead form – as in Four For See Beauties, in which a soft corpse is made to caress every surface it touches – or in imaginative hybrid sculptures. In The Scrawling Octopus (2022), she riffs on the octopus’s capacity for making ink, a material with obvious writerly connotations: the glass limbs of a harried-looking octopus are tangled among a scribble of chargers, lamps and smartphones. Another glass sculpture, This Means (2019), sees the octopus in maternal mood, its face a pink pair of breasts, its limbs comically proffering snacks, a nailbrush and a bottle.

For Prouvost, the octopus is both a uniquely embodied intellect – famously, most of an octopus’s neurons are in its arms – and a symbol for the primordial stuff of life. ‘I call her “she”, but in French it’s un pieuvre [masculine]. She’s so malleable. I think of that ability to transform as a very feminine quality,’ she says. ‘The octopus is in all of us,’ Prouvost told the press during a video tour of her commission for the French pavilion at the 2019 Venice Biennale. ‘For me it’s the beginning of humanity, it’s the beginning of the world and its subconscious. We all have her, but in our belly.’

There’s also the mind-boggling fact that the octopus tastes – as well as thinks – with its eight limbs. Prouvost tells me: ‘I struggle with the idea of the authority of sight. Why not smell, or touch or licking? From early in my life, I wanted all my senses to have equal power.’

Landed Here To See You With All Our Very Breasts (2023), Laure Prouvost. Courtesy Lisson Gallery; © Laure Prouvost

For Venice, she littered a watery blue floor with flotsam and jetsam – shells, seaweed, mobile phones, CDs, nets – alongside an octopus and other marine creatures, hand-made in glass by the maestros of Murano. In an accompanying film, Deep See Blue Surrounding You (2019), a merry band of dancers, musicians and magicians journeying from Paris to Venice describe their group as ‘an octopus’. Beneath the gallery was a tunnel, dug between the neighbouring French and British pavilions in a symbolic act of reconciliation.

Digging is another of Prouvost’s fixations. In 2013, she won the Turner Prize against stiff odds, ahead of Tino Sehgal, David Shrigley and Lynette Yiadom-Boakye. The winning work was Wantee: a film and installation commissioned by Grizedale Arts and the Tate for a Kurt Schwitters retrospective at Tate Britain. Prouvost created a grimy shack in the Lake District, which she filled with the furniture and knick-knacks that she imagined her fictional grandfather, a friend of Schwitters and an obsessive digger of tunnels, would have in his soil-speckled home. The story: that this art-world Wally has been lost down one of his own holes.

As a metaphor Wantee was not especially subtle, but its irreverence clearly struck a chord. Prouvost has that rarest of qualities in an artist: she can be properly, laughout-loud funny. In Grandma’s Dream, the film that formed part of Wantee, she wistfully intones: ‘In Grandma’s dream, Grandpa would finally admit that he loves painting bottoms – he’s just interested in painting bottoms, and not conceptual art.’ As off-the-cuff silly as it seems, there are theoretical underpinnings to all this: Freud, the grandfather of psychoanalysis, used metaphors of digging and excavation extensively in his writing. Like the archaeologist in search of artefacts, the psychoanalyst must dig through layer after layer of the patient’s psyche to reach the deepest treasure. Prouvost, though, is more likely to discuss the Mole Man of Hackney, who hit the headlines in 2006 when a court ordered an end to 40 years of burrowing under the homes of his neighbours, than she is to overtly refer to Freud.

Breasts appear throughout the artist’s work to a degree that would have given the great man cause to pull a little harder on his cigar. Prouvost’s boobs – she prefers that term – are alternately sensual, sexy, caring, enveloping and comical. In her Legsicon, she describes them drily: ‘Change with time, often painted by Grandad.’ There’s no mention anywhere, either in her work or in our conversation, of the writings of Melanie Klein and her object relations theory, though critics have certainly picked up on the connection.

Klein’s idea is of ‘the good breast’: how the earliest objects an infant interacts with will shape their development. As I watch Prouvost suckling her baby daughter in Four For See Beauties or look into the goggling nipple-eyes of her octopus mother in This Means, my thoughts range widely – from Klein to that Twitter meme parodying the writing of female characters by male authors: ‘She breasted boobily down the stairs.’ That her work provokes both thoughts simultaneously, the highbrow and the (extremely) low, is entirely characteristic. Entering Prouvost’s world can feel both like listening to a giddy toddler and to a drunken wit; alternately petulant, playful and profound.

As we wander through the ordered mess of cables, packing crates and artworks that will become her next exhibition, I ask her what her children make of her work, boobs and all. ‘They’ve had enough […] they’re a bit embarrassed,’ she tells me, laughing. It doesn’t sound like she minds too much. Whatever direction Prouvost goes in next, it’s impossible to imagine the artist losing this teasing combination of thoughtfulness and absurdity.

‘In the Mist Of It All, Above Front Tears’ is at the De Pont Museum, Tilburg, until 18 August.

From the March 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.