This review of Laura Knight: A Life by Barbara C. Morden was published in the July/August 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

It’s hard to know how exactly to classify Laura Knight as an artist. Not avant-garde, and hardly modernist; figurative but not academic, and certainly not dull. ‘One of the most popular artists of the 20th century,’ according to Rosie Broadley, curator of an exhibition of Knight’s portraits at the National Portrait Gallery in 2013 – and if ‘popular’ is not itself a damning term, would ‘middlebrow’ be worse? Widely liked works such as Ruby Loftus Screwing a Breech-ring (1943) and Self Portrait (1913) are scorned by modish critics. And although Knight has a growing reputation – two surveys open this year, at Penlee House in Penzance (until 16 September) and MK Gallery in Milton Keynes (9 October–20 February 2022) – the scholarly literature is sparse.

It helps to place Knight alongside her coevals Augustus John, William Orpen and Vanessa Bell to see the in-between generation she belonged to. Trained in late Victorian certainties disrupted by Post-Impressionism and abstraction, the cohort also included Stanley Spencer and L.S. Lowry. Knight’s art belongs in this expressive, figurative, confident mode.

Basing her book (revised from its first publication in 2014) on Knight’s published autobiographies, Oil Paint and Grease Paint (1936) and The Magic of a Line (1965), Barbara Morden characterises the artist as exuberant and impetuous, rapidly moving through enthusiasms and painting at speed. The Green Feather, a plein-air figure study in full colour, was allegedly finished in two days, notwithstanding a complete change from cloud to sun when the sky brightened. Morden’s lively biography mimics Knight’s restless progress, but there is a lot to cover.

Laura Johnson was born ‘in-between’ classes to a sprawling family of skilled workers and petit bourgeois traders based in Nottingham, where lace production was a principal industry. Her father walked out soon after her birth, and she was brought up, the youngest of three daughters, in an impoverished, resourceful all-female household. To avoid dependence on feckless men, her artistically gifted mother ensured the girls were trained to teach, and promoted Laura’s abilities. After a spell with lace-making relatives in north-eastern France, in 1890 at the age of 13 she was enrolled at Nottingham School of Art. Here she met the socially more secure Harold Knight, whom she would marry in 1903. Laura had just had her first success and sale, at the RA, with a mother and child in sombre Sickertian tones.

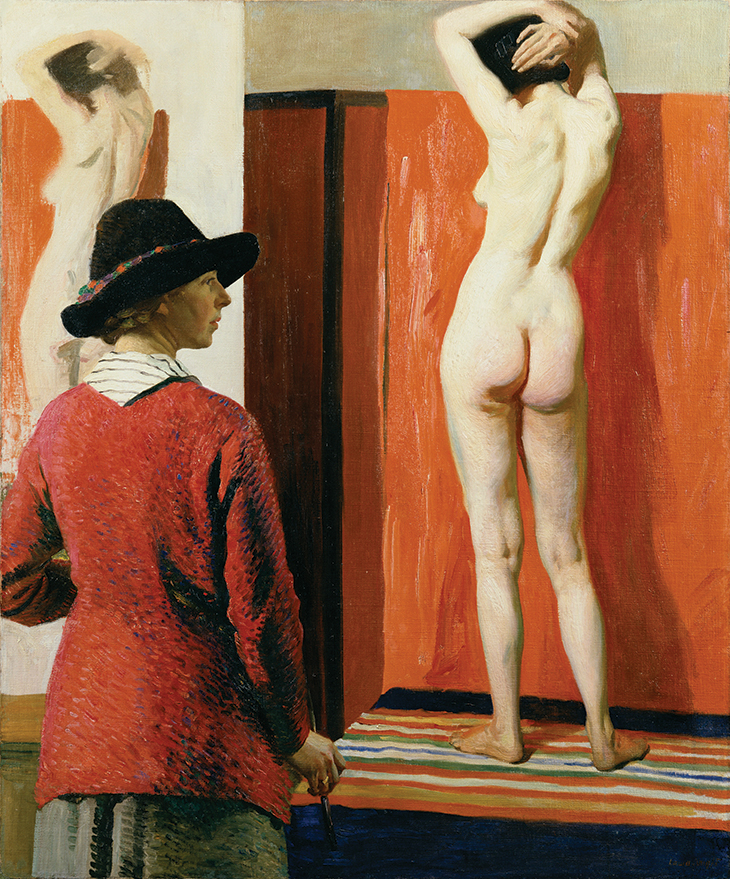

Self Portrait (1913), Laura Knight. National Portrait Gallery, London. © The Estate of Dame Laura Knight DBE RA 2021. All Rights Reserved/Bridgeman Images

Laura and Harold painted together in Staithes in Yorkshire, at Laren in Holland and then Newlyn in Cornwall, Laura developing a bright open-air palette for beach scenes with infants in dappled smocks and girls sun-bathing or standing by turquoise waves. She loved the social life of the Newlyn artists, with their picnics, plays, camping and skinny dipping. The chief evidence of ambition and originality is her Self Portrait of 1913, a profile perdu view of Knight wearing her trademark red jacket and black fedora, painting a rear-view nude of a slim model, her friend Ella Naper, standing against bold blocks of scarlet and brown. It was, and remains, a challenge to painters presenting naked, reclining and implicitly submissive women. As Pamela Gerrish Nunn wrote in her catalogue for the exhibition ‘From Victorian to Modern’ at Djanogly Art Gallery in 2006, as ‘thoroughly new women’, Knight’s subjects ‘roam freely at the liminal meeting of land and sea, thoughtful and self-possessed in the natural world which Knight makes an arena for their liberty’.

Morden quotes commentators who discern covert lesbianism in these liberated images, painted with ‘masculine’ vigour and bravura, and sometimes criticised as ‘aggressive nudes’. She does not probe Knight’s sexuality, however, and assumes that childlessness was a choice. Although a successful portraitist who lived into his eighties, Harold Knight remains something of a cipher until quite late in the narrative. Laura, as the book has it, was very much the centre of her universe.

Morden insists hers is a biography, not a ‘picture book’, but it is a shame that among the illustrations here many are black-and-white, and illegibly murky. Making pictures was Knight’s life. She hailed each new work as her best, which is perhaps reflective of the pleasure she took in the process of handling brushes, pencils, pigments, rather than of a sober assessment. Surprisingly, Morden does not inquire as to who proposed Knight’s damehood in 1929 – surely in response to her 1928 silver medal for a painting of boxers when the Olympic Games had art sections. It must have boosted her self-esteem enormously.

The Ballet Girl and the Dressmaker (1930), Laura Knight. Photo courtesy Sotheby’s / © The Estate of Dame Laura Knight DBE RA 2021. All Rights Reserved/Bridgeman Images

Dancers succeeded Cornish coves and cliffs when the Ballets Russes visited Britain; Knight attached herself to Anna Pavlova (who had settled in London), sketching ballerina and corps from the wings and in dressing rooms. The aim was pictorial grace, movement and glamour, allied to physical exertion and backstage realism. The later Ballet Girl and the Dressmaker (1930) depicts a workplace moment, where the muscular legs of the former are set off by the precise action of the latter, hastily mending a tutu.

A brief interlude in Baltimore, where Harold had a portrait commission, produced a clutch of strong, respectful depictions of African-American hospital staff. Back in Britain, circuses and gypsies yielded colourful scenes and sitters: clowns, bareback riders, race meetings and fortune tellers (framed by the door of the Rolls-Royce Knight used as her own daily caravan). She applied vigorous brushwork to these very English subjects, unromanticised, yet hinting at a wildness shared by the artist, who linked her own adventurous spirit to travellers and itinerant performers. The works were ‘Jolly, fresh, hefty, commonplace,’ according to one critic in 1939.

The Nuremberg Trial (1946), Laura Knight. Imperial War Museum, London (on display in the museum’s new Second World War Galleries from 20 October 2021) © The Estate of Dame Laura Knight DBE RA 2021. All Rights Reserved/Bridgeman Images

Knight’s final flowering produced paintings of women workers in the Second World War, including Ruby Loftus at her lathe in the Royal Ordnance Factory in Newport, and the under-appreciated Nuremberg Trial. Hermann Göring and Nazi accomplices are shown in dizzying perspective with urban conflagration behind; in the words of Philippe Sands, ‘an image of once-powerful men reduced to fearful spectators of their own imminent demise’. Wrapping up this sympathetic book, it is a great history painting and a powerful example of Knight’s talent.

Laura Knight: A Life by Barbara C. Morden is published by McNidder & Grace.

From the July/August 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.