London

In 2019 Kudzanai-Violet Hwami was selected as one of four artists to represent Zimbabwe at the 58th Venice Biennale. In the same year the young painter mounted her first institutional show, at Gasworks in London. Titled ‘(15,952km) via Trans-Sahara Hwy N1’ after the route from her birthplace in Zimbabwe, via her former home in South Africa, to her current home in the United Kingdom, the exhibition presented a series of vividly coloured, palimpsestic paintings that draw on family history and the specific details of these different locations. ‘I do like this idea that geography has been collapsed,’ Hwami tells me. Hwami and her family left Zimbabwe due to political unrest when she was nine, spending several years in South Africa before eventually moving to London more than a decade ago. ‘With the collapsing of geography and time and space, no longer am I confined in a singular society but simultaneously I am experiencing Zimbabwe and South Africa and the UK, in my mind. I’m in the UK, but I carry those places with me everywhere I go.’

In contrast to her busy 2019, this has been a year of quiet reflection for Hwami. ‘During Covid I was simply watching and waiting and seeing and wondering,’ she explains. We discuss the various cataclysms the world has witnessed this year, from the pandemic to police violence against Black people, climate disasters and political corruption. In the wake of so many catastrophes on such a large scale, it’s easy to feel defeatist. For Hwami, it’s important to focus on the smaller things that can be changed. ‘I think it begins at home,’ she says. ‘Water the garden that’s close to you.’

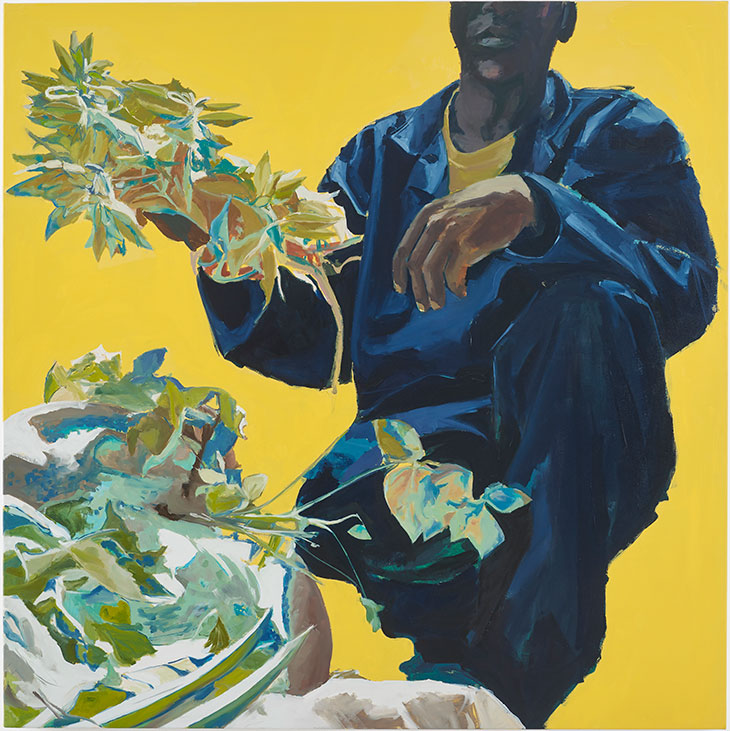

Medicine man (2019), Kudzanai-Violet Hwami. Courtesy the artist

To generate her work’s own sense of intimate proximity, Hwami often uses family photographs as a source for her paintings. Other works draw on photographs taken by Hwami as well as online images, including the scrolling squares of Instagram and Tumblr. Her subjects recline and pose comfortably, often in domestic settings, though Hwami’s dense layering of figures and cacophonous patterns – initially composed using digital collages before being transferred to canvas – suggest that family relations, and the idea of home, can be fraught. Rendered in molten reds, oceanic blues and other intense shades, her works hum with a sense of inheritance and deep untold histories.

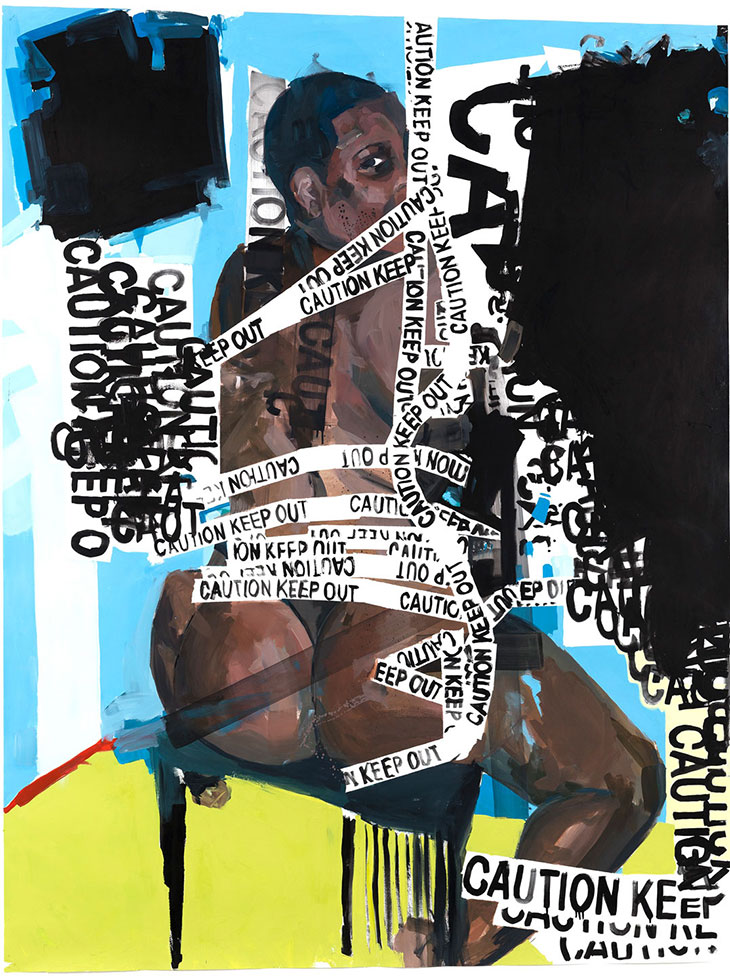

Through their exploration of personal identity, Hwami’s works touch on themes of gender, sexuality, race and violence, and they also display a wit and defiance that Hwami associates with Zimbabwean culture. Political satire and humour are the primary ways in which Zimbabweans can critique their government, Hwami explains. In her earlier works – such as Eve on an apple bottom (2016), which portrays an edenically naked Black woman plastered in caution tape – Hwami employs the techniques of satire. More recently, however, she sees herself moving away from overt political commentary and opening her work up to other interpretations. The subjects depicted in the exhibition ‘(15,952km) via Trans-Sahara Hwy N1’ included an array of family, friends and strangers that Hwami hoped would challenge the assumptions of audiences. Medicine man (2019), for instance, is the portrait of a healer with whom Hwami lived in Zimbabwe for a month, but in addition to conveying the animated beauty of his work, the painting also evokes the estrangement Hwami felt from her former home during this time. The healer’s face is only partly visible, cut off by the edges of the canvas.

Eve on an apple bottom (2016), Kudzanai-Violet Hwami. Courtesy the artist

Central to Hwami’s artistic project is the Black body, which she notes has in the Western tradition not always been an acceptable subject for portraiture. In the second half of the 20th century portraiture somewhat fell out of favour as a serious genre, yet Hwami is one of many artists around the world who are reviving the genre and reformulating it around the Black body. She mentions the American artists Henry Taylor and Kerry James Marshall and the British artist Lynette Yiadom-Boakye as major examples of this trend, and as inspirations for her own work. Eventually this resurgence of figuration ‘will go beyond the Black body,’ she says. ‘It will lift up portraiture as a genre for everyone. And that’s the beautiful thing about it.’

After her period of introspection earlier in the year, Hwami is back in the studio now and is set to complete an MFA at the University of Oxford’s Ruskin School of Art next year. At 27, she says that she cannot think of her already impressive career in terms of major themes or movements, except that her own family histories and personal narratives remain at the heart of everything she creates. ‘I’m still trying to discover it all,’ she tells me. ‘And it’s a journey; I want to see it as such. I don’t want to pin my work down.’