John Ruskin (1819–1900), the Victorian age’s foremost art critic, was born 200 years ago this February. In Ruskin and his Contemporaries (2018), a compilation of lectures and articles published to mark the occasion, Robert Hewison observes that ‘Anniversaries are arbitrary affairs’. But perhaps this arbitrariness is less revealing than the kinds of impetus and organisation that bring one anniversary to public attention over any other. Ruskin’s bicentenary has been in the planning for a long time: Ruskin To-Day, a body set up in 1995 to coordinate the centenary of his death, has circulated an impressively varied calendar of events, ranging from public lectures and symposia to exhibitions, student shows, and even a choral evensong. And this activity is not confined to the UK: there will be exhibitions at Harvard’s Houghton Library, at the Yale Center for British Art, and at the Mitsubishi Ichigokan Museum, Tokyo (which travels to Kurume and Osaka), as well as conferences in Venice, Pau, and San Marino. Hewison rightly suggests that anniversaries can bring ‘the past into the present; by making us revisit, and rethink, familiar material’. They also pose questions, as to the warrant for all this attention. Does Ruskin still deserve a place in the present? Is he in any sense our contemporary? And what, if so, is the appropriate balance between celebration and commemoration?

As with many Victorian figures, a pressing concern is what to do with those aspects of a legacy that might trouble or even appal us. Ruskin’s philanthropy was mixed up with the imperialist ferment of Oxford in the 1870s; and his attraction to childhood innocence places him in the company of Lewis Carroll and those ‘men in Wonderland’ whose ‘girlhood’ – to quote Catherine Robson – is hard and uncomfortable to categorise. In his politics and personal relations, he could be humane and kind-hearted, yet also high-handed and authoritarian. Ruskin’s legacy may not be precisely in tune with today’s attitudes, but he also caused a fair amount of outrage in his own time, through public spats with economists, the Anglican clergy, and, most famously, James McNeill Whistler. The more prurient and superficial responses of his contemporaries linger in our own time, as witnessed by the two-dimensional portraits of recent television and film: the BBC’s Desperate Romantics (2009), Emma Thompson’s Effie Gray (2014), and Mike Leigh’s otherwise sensitive Mr. Turner (2014).

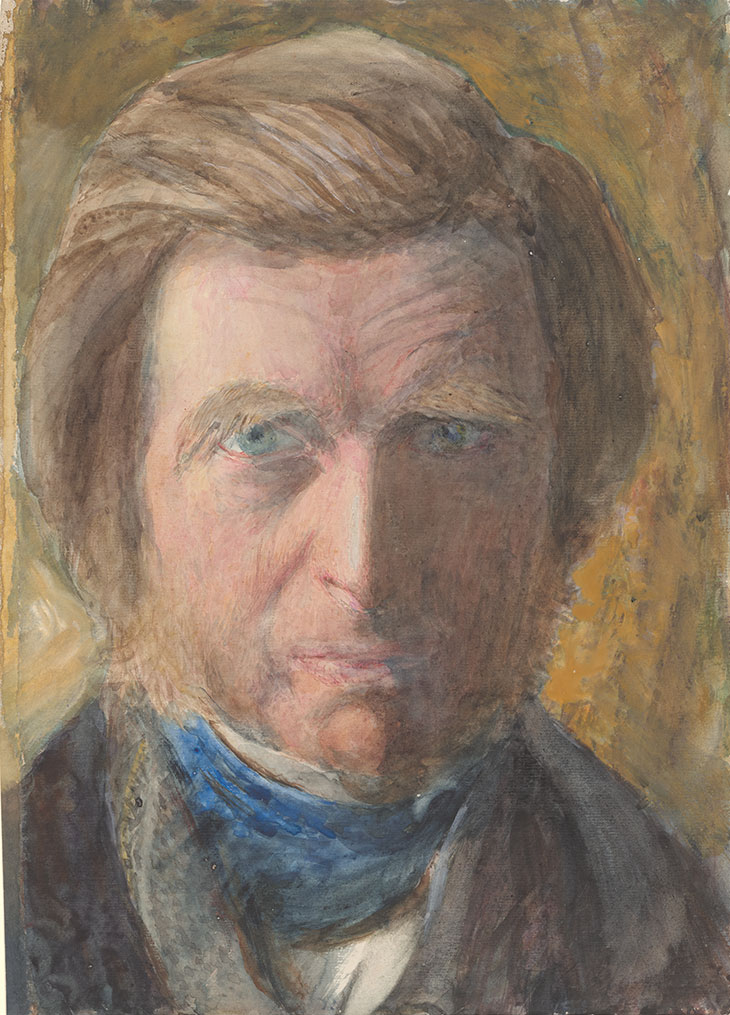

Self-Portrait, in Blue Neckcloth (1873), John Ruskin. Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Photo: Janny Chiu, 2018

Ruskin has remained a figure to reckon with all the same. He was J.M.W. Turner’s earliest and most fervent defender; he inspired aestheticism and the Arts and Crafts movement; he influenced the labour ethics of Tolstoy and Gandhi, and he was a source for the principles of the welfare state. His appeal has been strikingly ecumenical: a self-confessed ‘violent Tory of the old school’, he nevertheless topped a survey of the books most admired by Keir Hardie’s intake of MPs in 1906. Recent years have added new, or renewed, forms of influence. Ruskin’s dark premonition of atmospheric pollution – his Storm-cloud of the Nineteenth Century (1884) – has been largely vindicated. Concerns about plastic pollution in our oceans likewise echo his fretful attention to the cleanliness of rivers and the purity of springs. With the financial crisis of 2008, Ruskin’s much-derided political economy returned to view. Andrew Hill, then city editor of the Financial Times, explored Ruskin’s concept of the ‘honest merchant’, and this month publishes Ruskinland: How John Ruskin Shapes Our World. Others have pondered the relevance of a Latin inscription photographed and favoured by Ruskin, on the exterior of San Giacomo di Rialto, Venice: ‘Around this temple, let the merchant’s law be just – his weights true, and his agreements guileless.’

Binding all these legacies is Ruskin’s appeal to the importance of vision, understood not as passive experience, but as a trainable agent of personal and social transformation. ‘To see clearly,’ he observed, ‘is poetry, prophecy, and religion, – all in one.’ This last association is the focus of ‘Ruskin, Turner and the Storm Cloud: Watercolours and Drawings’ (29 March–23 June), an exhibition at York Art Gallery that explores the connection between Ruskin’s admiration of Turner and his close visual attention to buildings, mountains, and the weather (the exhibition travels to Abbot Hall Art Gallery, Kendal, from 11 July–5 October).

The View from My Window, Mornex (1862), John Ruskin. Lakeland Arts

The idea of a sustaining and sustainable attentiveness runs through an accompanying essay collection, edited by Suzanne Fagence Cooper and Richard Johns. A chapter by Howard Hull compares modern conceptions of climate change to Ruskin’s account of ‘a very particular type of “plague wind”’ that ‘brought symptoms of sickness, not vitality’. This perspective was informed not only by Romanticism, but by science. Since his youth, explains Hull, Ruskin ‘recorded his observations of the weather methodically, especially the blueness of the sky (of which he took measure with a cyanometer, a device created by the French alpinist Horace-Bénédict de Saussure)’. But the disciplines of Ruskin’s ‘close looking’ could also tip him out of mental balance, so that he found it hard to disentangle change from moral judgement, and environment from menace. Modern history became the record of a fall into faithlessness, while the polluted skies of Ruskin’s maturity warned not just of social malaise, but of a coming brain storm. His most serious mental collapse occurred in 1878. On the night in question he filled his diary with delirious reflections on Venetian history, and imagined himself summoned to combat the devil ‘in a naked condition’. These tribulations took a heavy toll on health and happiness; and yet Ruskin never lost his original sense of wonder in contemplating the created world. Writing as the director of Brantwood, Ruskin’s Lakeland home, Hull rightly returns us to the pictures on the wall of the author’s bedroom, to a set of ‘sun drenched Turners, alive with affection, cheerfulness and honesty: glowing with the warmth of a humanity at one with an earth they both loved’.

John Ruskin, Joan Severn, Peter Baxter and other members of Ruskin’s household photographed by John McClelland on Coniston Water, Cumbria, in 1895. National Portrait Gallery, London

A photograph from February 1895, showing Ruskin and his household on the frozen surface of Coniston Water, emits a similar kind of hope. The master appears here in his silent dotage, the torment and struggle over, and the mental powers stilled. And yet the mixture of activity and calm in this image feels consolatory: from the deeply scored ice the eye moves to a boy on skates, and then a gentleman on a primitive tricycle, and finally to Ruskin himself, miraculously seated in the middle of the lake. Commending the same scene in a previous year, Ruskin imagined ‘a marble field, as strong as the floor of Milan Cathedral, half a mile across and four miles down’. Ice had been a preoccupation ever since he pioneered the photography of mountain environments as a young man. A chapter by Robert Macfarlane applauds this aspect of his legacy: Ruskin’s portrait of the Glacier des Bois, he observes, is a ‘paradox of stasis and dramatic force’. Another piece, by the artist Emma Stibbon, presents a daguerreotype, Mer de Glace, Chamonix (1854) – taken by Ruskin and his manservant, Frederick Crawley – alongside her own image of the same spot, captured from the Montenvers observation hut at the same time of year. She finds the valley bare, ‘a dark moraine covered floor, almost completely devoid of ice’. Apart from alerting us to the remarkable extent of glacier melt, Ruskin’s original exposure reveals a photographic eye moving beyond simple landscapes into the abstraction of landscape detail, a kind of fractal awareness. Its subject, an ice field, has peaks and troughs resembling the solid, but slowly ‘perishing’, mountain range through which it passes.

Mer de Glace, Chamonix (1854), John Ruskin with Frederick Crawley. Ruskin Foundation (Ruskin Library and Research Centre, Lancaster University)

The major exhibition of the year is at Two Temple Place, a late Victorian mansion on the Embankment in London. ‘John Ruskin: The Power of Seeing’ (26 January–22 April) has been conceived by Louise Pullen of Museums Sheffield (the exhibition travels to their Millennium Gallery in May), and by the Guild of St George, which owns many of the works on display. Like the York show, it emphasises an active development of the eyes. But it also moves beyond things seen in the world to encompass Ruskin’s curatorial and museological philosophy, according to which museums were devoted to public access and visual study, not just preservation. At the core of the exhibition is a group of objects that Ruskin lodged in Sheffield, in a small, experimental gallery, perched on a hill within sight of the Peak District. Named St George’s Museum in honour of England’s patron saint, and of the same saint’s veneration in Venice, it announced his ambition for a ‘working man’s Bodleian library’, a treasury of books, minerals, medieval manuscripts, plaster casts and paintings, aimed at the local population of cutlers. Ruskin even designed the museum furniture, ingeniously combining the imperatives of preservation and display to create cases that anticipated modern curatorial methods. His mineral cabinets were lined with baize and topped with angled inspection glass. Straps were attached to wooden fittings for easy lifting, and the frames of paintings were designed ‘to slide into portable boxes’ for safe and efficient loan to other institutions.

The rear extension of St George’s Museum, Walkley, South Yorkshire, captured by an unknown photographer in c. 1885. © Collection of the Guild of St George/Museums Sheffield

The exhibition signals the backdrop of the museum in various ways: Stanley Royle’s Sheffield from Wincobank Wood (1923) visualises the city’s open vistas of chimney and furnace, while a sterling-silver and silver-gilt bracelet (c. 1940) by Joyce Rosemary Himsworth marks Sheffield’s metal-working heritage. Artisanal processes are the subject of The Putter (2014), a film by Shaun Bloodworth whose title (meaning ‘a putter-togetherer of scissors’) evokes the surviving metallurgical vernacular of Sheffield’s ‘little mesters’ (independent masters). Ruskin, crucially, did not want to turn cutlers into gentlemen. He wished instead to make them better craftsmen, by giving them access to art. He kept this connection in mind even when he showed them Old Masters. ‘The Ruskin Madonna’ (c. 1470) – a work unfortunately not travelling to the exhibition – was sold in 1975 to the National Gallery of Scotland. When Ruskin acquired the painting it was attributed to Verrocchio, an artist whose first training as a goldsmith evoked the museum’s founding purpose as a place where artists and artisans could rediscover common ground.

The Virgin Adoring the Christ Child (‘The Ruskin Madonna’) (c. 1470–75), attributed to Andrea del Verrocchio. National Galleries Scotland

In practice, social roles proved more mobile than Ruskin might have intended. One day a knife grinder named Benjamin Creswick stepped inside the museum. The experience was transformative: he became a sculptor, and finally master of modelling at the Birmingham School of Art. Major commissions included friezes for the façades of the Cutlers’ Hall, City of London, and at the Bloomsbury Library, Birmingham. Creswick’s story hints at gentrification, but became talismanic for Ruskin all the same, suggesting as it did sudden conversion and a mingling of art and craft at the level of biography. His contribution is aptly evoked in the exhibition by a terracotta bust he made of Ruskin, from 1887, and a terracotta relief entitled The Blacksmith’s Forge (1886). Leading in the opposite direction, a fine edition of Ruskin’s Unto this Last (1860) suggests the possibility of brainworkers becoming handworkers, bound as it was in the 1880s by T.J. Cobden-Sanderson, a barrister who turned his attention to bookmaking at the suggestion of William Morris’s wife, Jane.

Portrait Bust of John Ruskin (1887), Benjamin Creswick. © Collection of the Guild of St George/Museums Sheffield

Many of the museum’s objects were purchased or donated as aids to drawing. Ruskin’s studies of flowers and foliage advance a method of teaching pioneered years earlier in The Elements of Drawing (1857), a work whose observational exercises were developed at London’s Working Men’s College. Laws of perspective receded in favour of a resolve to ‘draw everything by the eye’, a practical instruction that evinced a combination of self-trust and responsibility in faithfully representing the world. Ruskin explained that he ‘would rather teach drawing that my pupils may learn to love Nature, than teach the looking at Nature that they may learn to draw’. It followed that the process of observation was as important as its end-product, indeed a faculty worth engaging for its own sake. The exhibition includes his Study of Spray of Dead Oak Leaves and Fast Sketch of Seaweed (Hornwrack) (both 1879), both from the early years of the museum. Each discovers a vitality beyond the usual limits of life: the first, in the delicate rhythm of autumnal oak leaves, and the second in the marine foliage of a ‘seaweed’ actually composed of small organisms, or zooids. Ruskin’s Snake’s-Head Fritillary, from the Ashmolean, and other individual flower portraits isolate a more fleeting beauty. A lack of background wash could suggest a clinical ‘study’, or a merely botanical record; but for Ruskin flowers were never just a means to the end of pollination. He viewed them, rather, as a kind of art, an offering to the human eye requiring no other purpose than beauty. A similar principle of gratuitous display – of tail feather, plumage and beak – emerges from the exhibition’s bird drawings, among them Ruskin’s Sulphur-Crested Cockatoo Sketched at Zoo (1877) and Turner’s Head of a Peacock (c. 1815), with its exemplary poise and detail. Ruskin especially valued the skill and decisiveness required for the ‘fast study’ of a shy creature. His eye was drawn to parts otherwise hidden by the whole, as one sees in his sketches of tracery and rock. The same principle applies in Ruskin’s Study of a Peacock’s Breast Feather (1873), and his study of a bird’s foot, a limb floating in white space, but somehow firmly planted.

Snake’s-Head Fritillary (c. 1870), John Ruskin. Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Ruskin’s education of the eye anticipated later visual practices in important ways. He was the father of classroom ‘observational drawing’; and in recent decades his understanding of drawing as a source of personal wellbeing has inspired the Campaign for Drawing (‘The Big Draw: Drawing Changes Lives’). His methods chime similarly with the meditative simplicity and visual focus encouraged by today’s ‘mindfulness’ movement. Ruskin, equally, did not confine himself to educational or rehabilitative aims: St George’s Museum was also entrusted with work of architectural preservation, and in this arena his reverence for the object also prevailed. Ruskin deposited casts taken from relief carvings on the Doge’s Palace, Venice, alongside detailed drawings of architectural features. They were executed by a trusted team of copyists, sent by him to Italy to produce ‘memorial studies’ of surfaces threatened by insensitive restoration. Works by J.W. Bunney stand out: his Palazzo Manzoni on the Grand Canal, Venice (1871), and Western Façade of the Basilica of San Marco, Venice (1877–82), a large-scale oil that formed the centrepiece of the museum’s rear extension. This part of the museum’s work influenced modern conceptions of buildings’ conservation as a matter of limited intervention, and careful record keeping. More locally, Sheffield became an unlikely resting place for the remains of a slowly vanishing Italian city, a site at which copies acquired something of the aura once reserved for their damaged originals.

Study of a Peacock’s Breast Feather (1873), John Ruskin. © Collection of the Guild of St George/Museums Sheffield

Several successful exhibitions have been devoted to Ruskin in recent years. In 2014, ‘Artist and Observer’, a revelatory show at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, demonstrated his underrated significance as a watercolourist. ‘John Ruskin: Le Pietre di Venezia’, a major exhibition at the Doge’s Palace last year, explored his contribution to the myth of Venice. As with Ruskin’s draughtsmanship, we can learn much from detailed views of a single attribute. But 2019 promises something much closer to a total view – to an encounter with the startling range and depth of the Ruskinian artistic and social intelligence. Once contemplated in all its variety, Ruskin’s vision crystallises as an undeniable cultural fact. He speaks to us of the past, and from the past, but also of the ways in which past things can be refashioned and recuperated. We may rightly question claims that he persists as a contemporary. Commemoration, at its best, avoids unthinking absorption or blind celebration. Whether or not we endorse his personal vision, Ruskin places a revealing pressure on vision itself. Seeing becomes an ethical faculty, a function as interested in the process as in its end-product. As such it recovers a form of vision hospitable to broader kinds of knowledge and self-awareness. His attention to the world favours innocence over scepticism, and intuition over learned principle; but it also contains its own rigours, privileging as it does what is seen above what we merely think or assume to be there.

To find out more about Ruskin bicentenary events worldwide, visit the Ruskin To-Day website.

From the February 2019 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.