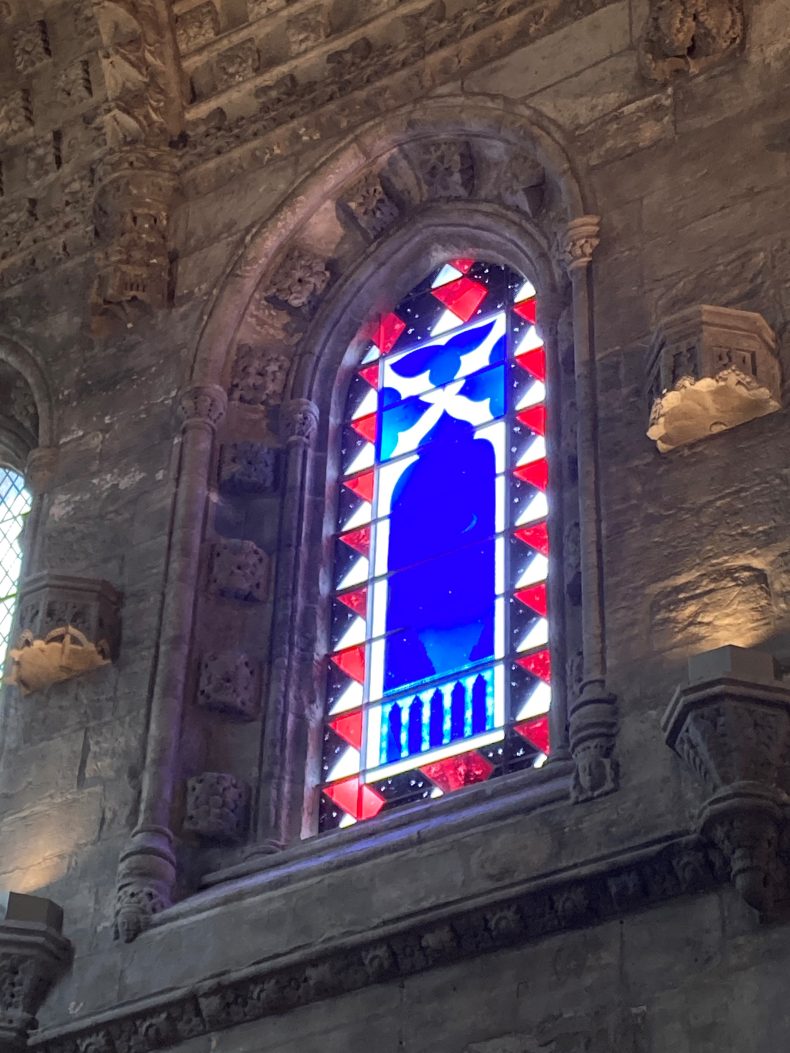

One of the final works made by the Pop artist Joe Tilson, who died last year at the age of 95, was a stained-glass window for the Rosslyn Chapel in Midlothian, just south of Edinburgh. Tilson’s distinctive vibrant colours now play – red or violet-blue and cobalt, depending on the season and the strength of the northern light – upon the sandstone carvings and the chapel floor.

It’s a powerful late work, especially because, at first, it seems so unexpected. How did a member of the grooviest generation, a contemporary and friend of Peter Blake, Richard Smith, Frank Auerbach and Richard Hamilton, come to make this lasting glow inside a Scottish gothic marvel from 1446? Even more mysterious, why does it work so well?

The stained-glass window in Rosslyn Chapel, designed by Joe Tilson. Photo courtesy Rosslyn Chapel

‘Perhaps it’s because it recalls the intense colours of medieval stained glass,’ suggests Helen Rosslyn, who commissioned the window with her husband, Peter St Clair-Erskine. The window replaced clear glass and sits alongside several muted, intricate Victorian stained-glass panes. ‘It’s very nice to add something that doesn’t compete with what’s gone before. We’re delighted the congregation like it so much; I was able to share with Joe before he died a photobook one of our chapel guides made of patterns the light makes through it, which was lovely.’

St Clair-Erskine is the 7th Earl of Rosslyn; his ancestors built the abundantly decorated, esoteric chapel in the 15th century. Any medieval stained glass that might have been in situ disappeared in the Reformation. The chapel became famous when Walter Scott’s bestseller The Lay of the Last Minstrel (1805) dramatised the myth that when a St Clair-Erskine died, the chapel would burst into flames. (‘Not a prophecy we set any store by,’ Helen says.) Visitors from Edinburgh came by coach and horse. But by the time the current Earl inherited the chapel in 1977 it was ‘rather niche, dark and damp, with algae beginning to grow inside,’ remembers Helen. ‘We really wanted to bring it back to what it should be.’ They set up a trust and started a process of conservation by covering the roof with a canopy in 1995 to prevent further rain damage, but £10 million was needed.

Light is reflected from Tilson’s stained-glass window on to one of the chapel walls. Photo courtesy Rosslyn Chapel

Then a certain Dan Brown visited, and the chapel’s history began another cycle. His thriller The Da Vinci Code (2003), in which some vital symbolism is discovered in the chapel, reignited worldwide interest; the coaches of visitors from Edinburgh were back. Tom Hanks and Audrey Tautou filmed part of the big-screen adaptation on location there, and Helen, whose background is in art history (she wrote and presented the BBC series Bought with Love: The Secret History of British Art Collections in 2013), embarked on a fundraising lecture tour in the United States. With support from the Heritage Lottery Fund, as well as many paying visitors, a marvellous restoration of the chapel was completed. Warm (or warmer), watertight and well lit, it resounded with the songs of a choir of local children at its official opening in 2012, in the presence of Camilla, then Duchess of Cornwall.

The window was a celebration of this achievement, and of 25 years of the Rosslyn Chapel Trust. Helen Rosslyn, who is currently director of the London Original Print Fair, liked Tilson and admires his work, and felt instinctively there was a fit. ‘He was a wonderful printmaker, and a great maker, with such a range of different skills.’

Tilson trained in joinery and carpentry at the Brixton School of Building at the age of 13. After national service, he went on to be at the heart of the so-called youthquake, studying at St Martins and the Royal College and representing Britain at the Venice Biennale in 1964. He had a lifelong love of Italy, living as a newlywed in Sicily, then establishing homes and studios in Tuscany and Venice, developing techniques like impasto in sand and wood – as seen in his Le Crete Senesi series (1995), inspired by the chalk hills around Siena – and spending time in the factories of Murano. His prints meld ancient patterns of marquetry and tilework with his bright ’60s geometry in a fusion that seems utterly natural.

Joe Tilson’s watercolour design for the Rosslyn Chapel window, 2020. Courtesy Cristea Roberts

In 2019 he contributed a 36-panel stained-glass work to the Royal Academy summer exhibition, Finestra Venezia, which won the top prize: the Charles Wollaston award. The simplicity of Tilson’s style had reached a kind of apex in his print series The Stones of Venice (2014–23). Working remotely with the conservator Mark Bambrough and his Scottish Glass Studios in Glasgow, Tilson finished the window in 2021. A range of his prints, which ‘speak the same language’ as the window, will be on display and for sale by Cristea Roberts Gallery at the London Original Print Fair this month.

‘Some see a Saltire in the window, others a Venetian ogee,’ says Helen. ‘It’s rather fitting because the chapel is full of so many stories in the stonework, but you’re never quite sure what they are, angels playing the bagpipes and elephants and camels, and so on.’ It’s fitting that a respected 20th-century artist has added a new abstraction. ‘The first rule with a 15th-century chapel, of course, is: don’t mess it up,’ says Helen. ‘We love the window’s timeless quality. And I think, although Joe wasn’t conventionally religious, there is a spirituality to it as well.’

The 39th London Original Print Fair is at Somerset House from 21–24 March; Helen Rosslyn will be in conversation with Sophie Lindo, talking about the window and Joe Tilson, on Sunday 24 March at 2pm.