The first display in ‘Fashion City: How Jewish Londoners Shaped Global Style’, an exhibition at the Museum of London Docklands, is perhaps the simplest. Unlike the riches that come later – natty shoes, elaborate beading, feathered hats, brocade that’s seen better days – this glass cabinet holds three unflashy items, their worn leather surfaces gently lit. There is Trude Tausinger’s handbag, used to store her documents and treasured photographs when she fled Vienna in September 1938. There is the Seelig family’s trunk – the only one they managed to take with them when they escaped Dresden in April 1939 – containing photos, a prayer book, and some fur coats and a microscope they later managed to sell. And there is Judith (Juci) Laszlo’s suitcase, carried by the five year old when she was brought to Britain from Czechoslovakia as part of the Kindertransport rescue effort from Nazi-controlled territories in the late 1930s.

Evening gown by Rahvis (1952). © Museum of London

It is a powerful beginning to a show that tells a story of persecution and ingenuity, of lives upended and rebuilt over the past 150 or so years, via that most intimate – and in this case, fitting – of objects: the garment. Of some 200,000 Jewish immigrants who arrived in Britain in the late 19th and early 20th century up until the Second World War, many of them fleeing pogroms and anti-Semitic sentiment, more than half worked in some capacity in the textile and garments trade. Tailors and dressmakers’ workshops proliferated in the East End, joined by shoemakers, silversmiths, leatherworkers, embroiderers and, in the case of the Polish couple J.H. and M. Fischer who had a shop on Hanbury Street, umbrella makers. Offering a compelling tour through Jewish contributions to British fashion, ‘Fashion City’ draws a connecting thread between these businesses and later generations of designers who embraced the swinging ’60s with boutiques on Carnaby Street and ateliers in Mayfair.

J.H. & M. Fischer outside their umbrella shop, Spitalfields (1919). © Museum of London

Arranged geographically rather than chronologically, the show walks the viewer from east to west London. In the first half of the exhibition one can explore a replica of a tailoring workshop (sales slogans include ‘GOOD CLOTHES give prestage [sic], poise & dignity to your appearance!’ and ‘The man who maintains his smartness is always in demand!’) and enjoy the many photos, oral histories and objects that bring to life an ever-evolving hub of trade and manufacture. This is a story not only of Jewish history, but also of different waves of migration that later brought communities from the Indian subcontinent to East London – many of whom also entered the clothing business. A beautiful photo taken by Margaret Macdonald in 1974 shows a building in Spitalfields that has variously been used as a Protestant chapel, synagogue and mosque.

Bellville Sassoon coat worn by Princess Diana. Fashion Museum Bath

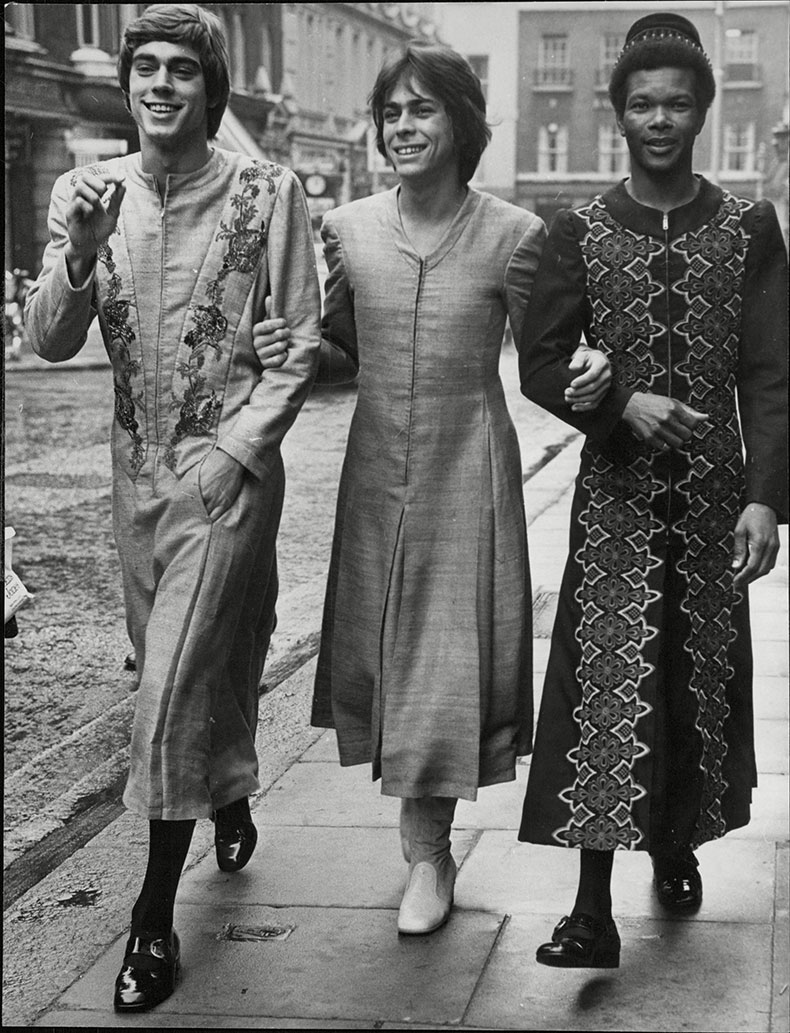

The second half of the show is accessed by a mock-up Central line tube tunnel, transporting us to the heart of London’s retail district in the ’60s and ’70s. It’s a clever touch – compelling without being gimmicky, complemented by the shop windows and boutique interiors on the other side. Here one enters an era of glitz and glamour, where the nascent rise of the high street vies with the more established allure of high-end designers. Flight-of-fancy hats by Otto Lucas (his designs graced the cover of British Vogue countless times) are joined by some fabulous pieces by Cecil Gee, the Rahvis sisters and Mr Fish, who dressed celebrities including David Bowie, Mick Jagger, Muhammad Ali and Jimi Hendrix in his trippy, free-flowing designs. David Sassoon’s sketches for Princess Diana are a highlight, annotated in pencil by Di herself, who apparently liked her shirt dresses sans extra bows.

Men’s Fashions by Mr Fish. Photo: Jimmy James/ANL/Shutterstock

So often a fashion exhibition can just feel like dresses in glass boxes. It’s a curatorial conundrum: how do you bring alive that which is usually animated by the human body? What can be done – beyond bringing in videos or interactive dressing up corners (this show has a fun wedding photo studio) – to make the viewer feel that what they are looking at and learning about is a lived history, rather than something perfectly preserved and ultimately static? ‘Fashion City’, however, is immersive and brilliantly assembled at every turn, with the curator Lucie Whitmore ensuring that this is not just an account of industry and innovation but the shifting fabric of a city. The exhibition unlocks a store of memories, legacies, tragedies, triumphs and everyday jobs. Every battered handbag and flouncy wedding dress reveals its own, intimate account of its makers and wearers.

‘Fashion City: How Jewish Londoners Shaped Global Style’ is at the Museum of London Docklands until 14 April 2024.