From the November 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Despite the trip back in time promised by this massive survey of Jasper Johns’s work now on view at two venues at once, ‘Jasper Johns: Mind/Mirror’ instead repositions the painter as a poet laureate of our altogether less confident present. The brash American Flag of 1954–55 that announced – with almost comic heraldry – Johns’s arrival on a scene still dominated by Abstract Expressionism, and which introduces the Philadelphia portion of the survey, is here a bait promptly switched. Not that Johns abjured further flags. Nor have the exhibition’s two curators, Carlos Basualdo at the PMA and Scott Rothkopf at the Whitney, but they do show Johns, now 91, to be most comfortable in shadowy zones where ‘things the mind already knows’ – his famous term for ordinary objects and images – cleave and multiply, circle back on themselves, put their faces to the wall, and are turned upside down and inside out.

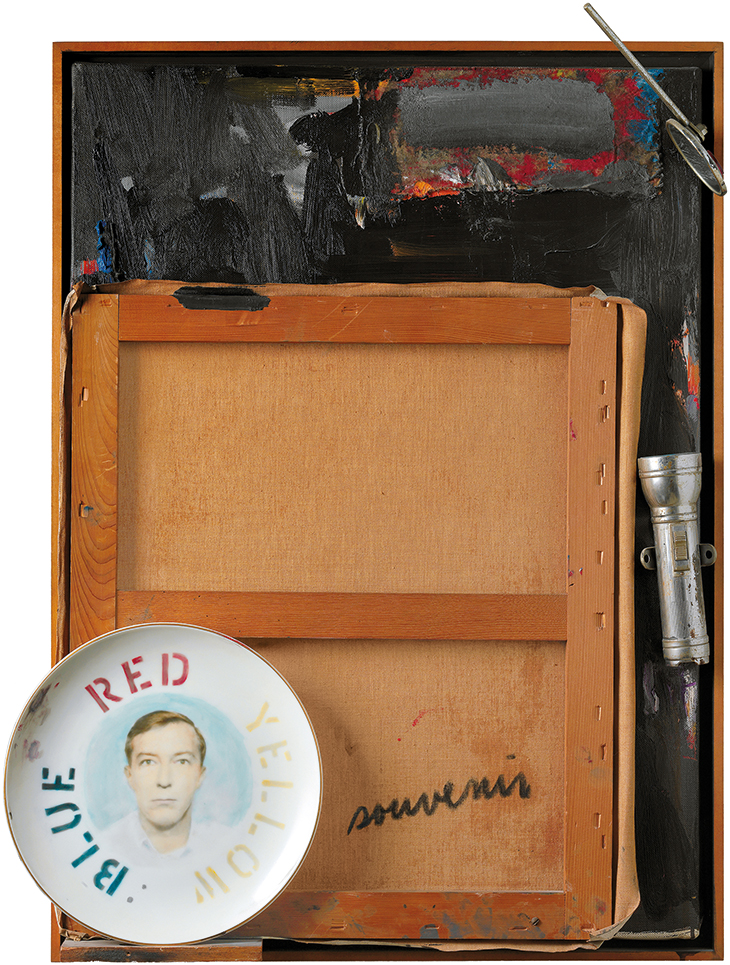

Johns began, Wittgenstein-style, with visual signs defined by their use, specifically those that carve up the physical world: maps, targets, numbers, letters, but also thermometers, flashlights, cutlery. Field Painting (1963–64) has a switch on its surface for turning on the neon R of Red; the three-dimensional letters of the other primary colours, named below it, are magnets to which studio objects are interchangeably attached (a knife, a coffee can, a brush with a metal band).

0 through 9 (1960), Jasper Johns. Private collection. © 2021 Jasper Johns/Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, NY

But it is not Johns the semiotician who now beckons. Hindsight allows us to see more clearly the context in which his work was formed, when Cold War surveillance coincided with relentless attacks on gay men for whom concealing and detecting coded behaviours became imperative. Writing at unwonted length about Watchman (1964), a grimly compelling painting with an inverted chair at the top that tips out a sallow bare leg, Johns once explained that the titular figure falls into a ‘trap of looking’ and ‘takes away no information’, while a spy ‘must remember’, and is at pains to make himself obscure. As so often with Johns, the formulation describes a confoundingly unmatched pair.

Dream logic is a continuous thread. Choices made to enhance facticity – the use of encaustic, which solidifies each brush stroke, and of casts that objectify body parts – are combined with a sense of reverie that this survey emphasises. Johns’s association with Duchamp is standard critical fare; less so, the kinship of his early assemblages with the work of Joseph Cornell. The many paintings of numbers on view in Philadelphia, some overlaid to the point of illegibility, others sorted into grids, or framed one by one, are often cloudy grey or ghostly white, though some spin deliriously through the spectrum. One tiny example of gridded digits daubed in warm colours (it is in the artist’s collection) could have been painted by Vuillard.

The first Flag appeared to Johns literally in a dream. The white, red and black flagstones that became a recurring motif were spotted on the facade of a store in Harlem. He glimpsed the crosshatch pattern on the side of a car, while he was driving. Flags, maps, targets, letters and numbers are irredeemably drifty; lacking the fixed scale of physical objects, they are familiar to the point of invisibility. Colour-reversed American flags invite the long stare that restores the flag’s true colours as afterimages. If Johns at first favoured the kinds of indexical procedures that produce body casts and even bite marks, he came to prefer photographs and shadows.

Corpse and Mirror II (1974–75), Jasper Johns. Collection of the artist. © 2021 Jasper Johns/Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, NY

Melancholy abounds. The first gallery in the Whitney show, titled ‘Disappearance and Negation’, presents the harrowing, thunderous charcoal and pastel Diver (1962–63), which pictures one pair of hands raised in alarm and another pair plunging down, sweeping a futilely graceful semicircle on the way. On the other hand, the Corpse and Mirror series – its title nods to Exquisite Corpse, the Surrealist game of random composition – is among Johns’s most vibrant and playful, featuring big crosshatch patterns in bright primary colours that mirror each other kaleidoscopically, sometimes aligning at the painting’s edges as if reaching around its nether parts.

Between the mid 1960s and early ’70s Johns made several grand, encyclopaedic paintings laying out his visual propositions about perception and representation; like other epic conceptual (and minimalist) exercises of the time, they turned out to be neither exhaustive nor conclusive. In the 1980s, he turned towards autobiography and a paradoxical hermeticism. The Seasons (1985–86), his most sentimental paintings, are also his most airless – jigsaw puzzles of variably decipherable images, including the outlined shadow of a boy, photos of the gallerist Leo Castelli and the Mona Lisa, and a few optical tricks reshuffled from one work to the next.

Souvenir 2 (1964), Jasper Johns. Collection of Barbara and Richard S. Lane. © 2021 Jasper Johns/Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, NY

Better by far are the Catenaries that began in the late 1990s. Among Johns’s most abstract works, they involve lengths of ordinary string slung from inclined wooden slats, like cables from the piers of very fragile bridges. Most are grey, although there is a whitish one that suggests, rather hauntingly, laundry on the line.

Quiet nostalgia will not be Johns’s final mood. His most recent works, some in ink and others in Sculp-metal, depict jaunty little skeletons grinning maniacally. Many sport a tiny fedora, several a walking stick. A few skip rope, transforming the catenary curve into an accessory for a quick jig with death. In the ink drawing Six Artists at Work (2020), stick figures busy themselves along the bottom, a skeleton sits above on a giant skull, and – the central image – a big, delicately rendered cock, dripping ejaculate, aims at a ripe orifice. Who would have thought? Looking mortality in the face, Johns seems to be having a very good time.

The catalogue, like the exhibition, is loosely chronological and otherwise organised by oddly assorted categories. Contributing writers range from the novelist Colm Tóibín to painters Carroll Dunham and R. H. Quaytman, and from curator Drew Sawyer (on ‘Queer Art Histories’) to artist, choreographer and writer Ralph Lemon (on the Jim Crow-era South Carolina in which Lemon’s mother, like Johns, was raised, and on the racism to which Lemon says Johns paid ‘emphatic cultural inattention’). There have been reports of the two host institutions jockeying for important works, but both book and exhibition suggest a deep and thoughtful curatorial exchange.

Delayed for a year by Covid, ‘Mind/Mirror’ should have followed, in New York, the career survey at the Met Breuer in 2020 of Gerhard Richter, two years younger than Johns and his main rival for obstinate silences, for making figuration a conceptual project, and for the enduring nature of his influence. Other artists with whom Johns invites comparison include Roni Horn, for her serial presentations of not-quite-identical photographs or sculptural objects; Jean-Michel Basquiat (were he and Johns looking at each other’s renderings of skulls in the 1980s?); and Bruce Nauman, whose work in nearly every mode seems more indebted to Johns than ever. In their work as in his own, Johns lives on, surely a painter for our time.

‘Jasper Johns: Mind/Mirror’ is at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and Whitney Museum of American Art, New York until 13 February 2022.

From the November 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.