It can be suggested without much cause for bloodshed that there were at least three geniuses at work in the Bloomsbury Group. There was the modernist author Virginia Woolf, the brilliant economist John Maynard Keynes, and the curator and critic Roger Fry – Paul Nash’s ‘shark in aesthetic waters’ – the man who did so much, rightly or wrongly, to shape British approaches to modern art in the first decades of the 20th century. One might even argue the case for Lytton Strachey, who found fame and wealth with his satirical biographical collection, Eminent Victorians in 1918; or (at the fringes of the group) another significant novelist, E.M. Forster. What an extraordinary crop of talents.

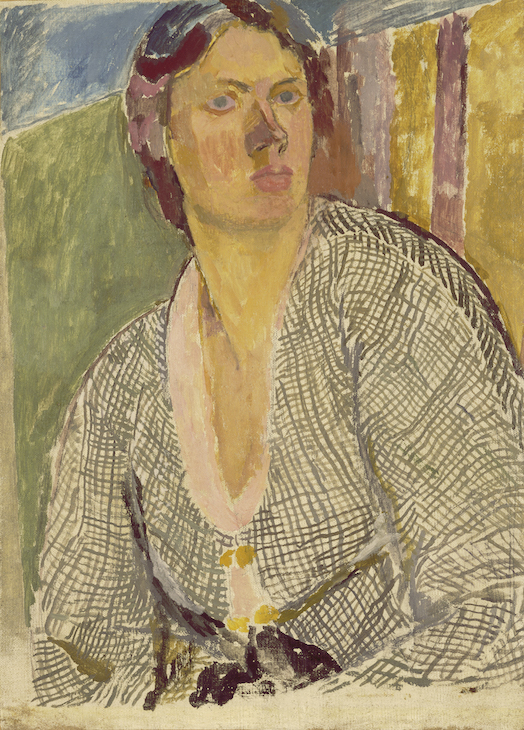

Self-Portrait (c. 1915), Vanessa Bell. Yale Center for British Art, New Haven. © The Estate of Vanessa Bell, courtesy of Henrietta Garnett

To think of Bloomsbury, however, is to think simultaneously of art and literature. (Yes, of course, we think of sex, too – as well as a wholehearted rejection of the mores and conventions of late Victorian and Edwardian society – but there’s been plenty written about that already.) I first visited Charleston, Bloomsbury’s East Sussex country outpost, in 1994, and was instantly fixated by this astonishing relic of lives lived in devotion to aesthetics. Like Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge, Charleston spoke of taste, sophistication, culture, and rustic unconventionality. Everything, from the curtains to the carpets, the pots to the paintings, reflected an ideal of art and home that rejected Victoriana and embraced Bohemia. But still, despite this, something about Bloomsbury left me cold. I think this derived as much from the paintings made by the Bloomsbury artists themselves as it did from the sense of discomfort one got from the wider group’s sometimes snobbish and highbrow sense of its own importance.

Since the art of Bloomsbury is the life of Bloomsbury it is hard to divorce one from the other; up until now it has been hard to separate Vanessa Bell from both Charleston or from her friend, partner, erstwhile lover, collaborator and lesser talent, Duncan Grant. Dulwich Picture Gallery, in another of its fantastic line of exhibitions devoted to modern British artists, has given Bell a major show – featuring more than 100 works – and catalogue entirely of her own. It is the first time she has been seen independently from the rest of Bloomsbury, and it’s long overdue. As the show’s co-curator, Ian Dejardin, observes, ‘Bloomsbury attracts extremes of opinion – it is the Marmite of British art.’ Bell deserves to be assessed on her own merits.

Iceland Poppies (c. 1908–09), Vanessa Bell. Charleston Trust, East Sussex. Photo: Matthew Hollow; © The Estate of Vanessa Bell, courtesy of Henrietta Garnett

I must admit that I find much of Bell’s work hard to appreciate. Studland Beach (c. 1912) is undoubtedly a great work, and certainly one of the very best early responses to Post-Impressionism’s assault on English sensibilities. But her portraits (which are the focus of the exhibition’s opening gallery) are far less attractive. One would be hard-pressed to deduce from her painting of Iris Tree that here was one of the great beauties of the age; it has none of the sensuality of the famous portraits by Man Ray, for example. To the exhibition’s co-curator, Sarah Milroy, however, Bell’s portrait of Tree abandons ‘conventional beauty’ in favour of ‘honesty and depth over ingratiation’, giving us ‘an image of female force’ possibly unrivalled in the previous history of British art. I find it difficult to see the painting in this way; it lacks the subtle power of Bell’s earlier works, such as the haunting beauty of Iceland Poppies (c. 1908–09), or the gentle simplicity of the coeval portrait of her friend Saxon Sydney-Turner at the piano. In both these paintings we glimpse the possibility of Bell as another Gwen John: sensitive in her approach to the subject, subtle in her palette and brushwork; works oddly urgent in their stillness.

Design for Omega Workshops Fabric (1913), Vanessa Bell. Yale Center for British Art, New Haven. © The Estate of Vanessa Bell, courtesy of Henrietta Garnett

Progressing through the galleries at Dulwich, it becomes clear that the sum of Bell’s art is much greater than its parts; as Charleston works as a whole, so the paintings, fabric designs and book jackets here combine to create a cacophony of colour – particularly in the room devoted to her Omega Workshop designs (often made in collaboration with Grant). While up-close some works appear rushed – she often seems to have a ‘that will do’ attitude to her brushstrokes – en masse they charm and intrigue. Some of the still lifes and interiors, where the colour really breaks out – Tea Things or The Other Room, for example – are simply marvellous. Too often, though, the earth tones have a tendency towards monotony.

The Other Room (late 1930s), Vanessa Bell. Private Collection. Photo: Matthew Hollow; © The Estate of Vanessa Bell, courtesy of Henrietta Garnett

Was Vanessa a genius with paint like her sister Virginia was with words? No. Does that matter? Not really. As she herself wrote early in her career, ‘I believe all painting is worthwhile so long as one honestly expresses one’s own ideas. One needn’t be a great genius – all the second-rate people are worth having so long as they’re genuine, because of course one always must have something of one’s own to say that no one else has been able to say – and that’s always interesting – but the moment one imitates other people one’s done for.’

Though Bell clearly found great joy in the Post-Impressionist message of artists such as Henri Matisse, it was ultimately a wrong turn for her. She is never ‘second-rate’, but she often comes too close to imitation, and one sometimes wonders whether she would enjoy such stature if it were not for her famous friends and famous sister. This is not intended to demean Bell as ‘just’ another woman artist. She was certainly the best artist in her immediate circle, superior to Fry or Grant. Studland Beach deservedly stands shoulder to shoulder with anything painted by Augustus John, Spencer Gore, Stanley Spencer, or any of the other British artists contending with the new modern movements immediately before the First World War. But despite moments of joy, one is still left with the lingering taste of Marmite.

‘Vanessa Bell’ is the Dulwich Picture Gallery, London, until 4 June.

From the April issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here