From the January 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

The American sculptor Isamu Noguchi is today best known for two design pieces. The first is a glass-topped coffee table with a sculptural wooden base that became such a mainstay of well-heeled taste that there was an early 2010s blog about interior design clichés called ‘Fuck Your Noguchi Coffee Table’. The second is the Akari lamp, a spheroid of washi paper placed over a frame of bamboo and wire, which was ubiquitous in middle-class interiors in the 1970s and ’80s, although generally in the form of cheap imitations.

This penetration into the everyday was what Noguchi always wanted from his work, and what he believed sculpture should want. But it means that he is now seen more as a designer than an artist and this, in part, is what this retrospective currently at the Barbican (then travelling to the Museum Ludwig and the Zentrum Paul Klee) aims to correct.

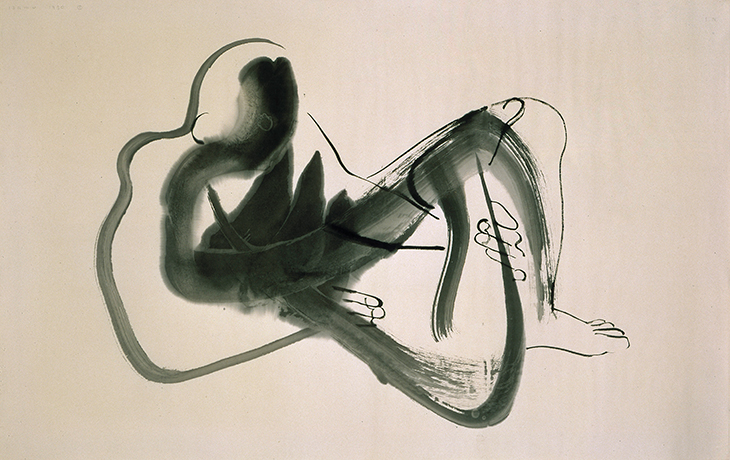

Peking Brush Drawing (1930), Isamu Noguchi. The Noguchi Museum Archives. Photo: Kevin Noble; © INFGM/ARS-DACS/ProLitteris/VG Bild-Kunst

Isamu Noguchi was born in Los Angeles in 1904 to an Irish-American mother and a Japanese father. He spent his early years in Japan, returning to the United States as a teenager. After working briefly for the sculptor Gutzon Borglum and taking evening classes in art, he abandoned a medical degree at Columbia University to devote himself to making portrait busts, before travelling to Paris to work in Constantin Brancusi’s studio. He emerged a committed modernist.

In 1929, Noguchi met the architect and industrial designer R. Buckminster Fuller in New York and the pair began to collaborate. Noguchi contributed to the form of Fuller’s ‘Dymaxion’ car, a streamlined, lightweight aluminium vehicle. ‘Dymaxion’ is a compound of ‘dynamic, maximum, tension’, and Fuller provided the young artist with an exciting, utopian direction for his energies. Noguchi’s bust of Fuller, from 1929, is of course plated with chrome; Bucky (1943) is a hanging tensile structure of string and wooden struts. Miss Expanding Universe (1932), a suspended female form in aluminium, is part aircraft, part benevolent angel.

R. Buckminster Fuller (1929), Isamu Noguchi. Private collection. Photo: F.S. Lincoln; © INGFM/ARS-DACS/ProLitteris/VG Bild Kunst/Penn State University Libraries

Noguchi’s enthusiasm for machine progress verges on the Futurist: ‘The new materials remake the world. We live in a tensile world of space. […] It is the world of the airplane, of speed – my world.’ But there’s none of the Futurist yearning for obliteration; as a socialist, Noguchi regarded the death instinct as capitalist, and war and bigotry as ‘smoke from that fire’. Humanity stayed firmly in sight, most clearly in a series of playgrounds Noguchi designed for New York, adventurous landscapes of steps and valleys, derived from observation of how children use the adult-scaled world around them. Unrealised, they exist as small bronze casts.

The Second World War delivered a series of harsh blows to Noguchi’s idealism. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, Japanese-Americans in the western United States were thought potentially unreliable and interned; though exempt, Noguchi volunteered to join them, and went into a camp at Poston, Arizona, where he tried to develop crafts programmes and playgrounds, without success. A series of blasted, lunar reliefs are the main legacy of that experience, influenced by the extremity of the Arizona landscape.

Poston and the war left Noguchi disillusioned, but his peak years as an artist were to follow. Monument to Heroes (1943) is a fragile, unsettling totem of string and bones, suggesting bodies blown apart. He began to experiment with slate and thin slabs of Georgia marble. These are smoothed into driftwoody shapes and hung together without fixings, as in traditional Japanese joinery. The tension and palpable physics of the Fuller years returns; not in taut, confident forms, but dangling, delicate and vulnerable. At the same time, Noguchi was designing set elements for Martha Graham, and the balance and poise of dance tells everywhere. These traumatised pieces are irresistibly more interesting than the sturdy, earthy, rocky works of later decades.

Trinity (Triple) (1945), Isamu Noguchi. Isamu Noguchi Foundation Garden and Museum, New York. Photo: Kevin Noble; © INFGM/ARS-DACS/ProLitteris/VG Bild-Kunst

It’s not all delicacy and lightness, though. In 1952 Noguchi designed a memorial for the dead of Hiroshima, although it was not selected. It was an arch, but far from triumphal; instead, a squat, swollen half-doughnut of polished black granite. The cyclopean interlocking sections of its armoured surface suggest both the assembly of aircraft and the bomb itself, or the split-second photographs of the Trinity nuclear tests, fearful domes roiling with uncontainable power. (Noguchi directly referred to those tests in Trinity (Triple) [1945], surely one of the earliest artistic responses to the Bomb.)

Akara 25N (1968), Isamu Noguchi. Isamu Noguchi Foundation Museum and Garden, New York. Photo: Kevin Noble; © INFGM/ARS-DACS/ProLitteris/VG Bild-Kunst

The memorial is appropriately ominous, even on a small scale. The Barbican displays it in close proximity to an Akari of a much later date, as if to show the poles of Noguchi’s post-war work, or promising a sunrise after that midnight. Noguchi continued to experiment with heavyweight stone monuments such as Walking Void #2 (1970) and the drilled, rough-hewn form of The Inner Stone (1973). He hankered to make land art and massive earthworks. He did, at least, get to create a few playgrounds, although they had to masquerade as ‘gardens’ and ‘plazas’: the Sunken Garden at Chase Manhattan Bank Plaza, New York (1961–64), fountains for Expo ’70 in Osaka, Piedmont Park in Atlanta and others. These are exhibited in the form of contemporary films. The darkened niche in which we view them feels like a footnote against the warm washi-diffuse glow of the main gallery, but it’s one of the more affecting parts of the exhibition, where a lifelong dream of sculpture, landscape and joy was finally realised. But after 1950 it was the Akari – cheerful, innocent, trooping like Minions – to which Noguchi returned and to which the visitor is repeatedly drawn. The utility of the Akari, and their great familiarity as a form and a fixture, has led to a persistent underestimation of Noguchi. Both in his lifetime, and in recent days, his exhibitions have been compared to lighting showrooms.

Is that fair? Florence Ostende, curator of the Barbican exhibition, stops short of an assertion of greatness and instead calls Noguchi ‘one of the quintessential sculptors of the twentieth century’. This is a subtle claim to make, more intelligent than a dubious superlative. A pure essence of the 20th century, yes. Not only did Noguchi live across its span, he faced up to its extremes of promise and horror, and embodied that confrontation in his fascinating, fallible work.

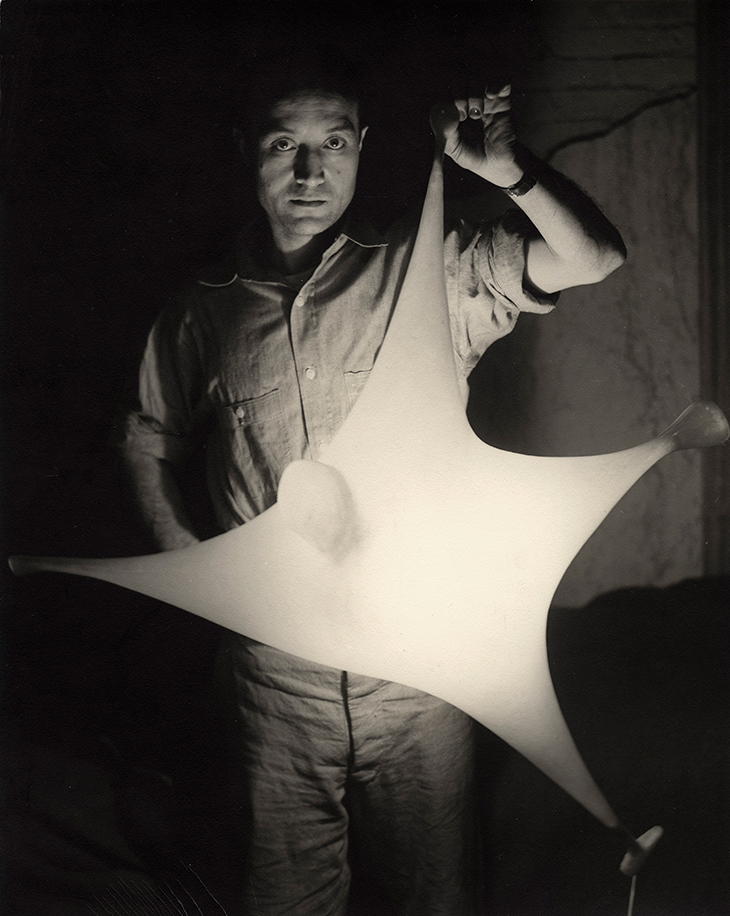

Isamu Noguchi photographed with study for ’Luminous Plastic Sculpture’ in 1943 (detail). The Noguchi Museum Archives. Photo: Eliot Elisofon; © INFGM/ARS–DACS/Eliot Elisofon

Will Wiles is the author of three novels: Plume, The Way Inn and Care of Wooden Floors (all published by 4th Estate).

‘Isamu Noguchi’ is at the Barbican Art Gallery, London, until 30 January.

From the January 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.