‘My early childhood was spent on the High Veld,’ Irma Stern wrote in ‘How I Began to Paint’ (1926). ‘Its vast largeness was one of my first impressions of this world so full of beauty – stretches of yellow plains with the blue, blue sky above and the dark figures of natives forming silhouettes against its transparency.’ In 1954, her acclaim in South Africa unassailable after a successful run of shows in London, Paris and Venice, Stern told a reporter that she had been born in a mud hut while her mother was on her way to the village hospital. Artistic identity is a complex thing, a compromise between public performance and private truth. In a diary entry from her late adolescence, referring to her early beginnings, Stern admitted, ‘I can’t remember it at all.’

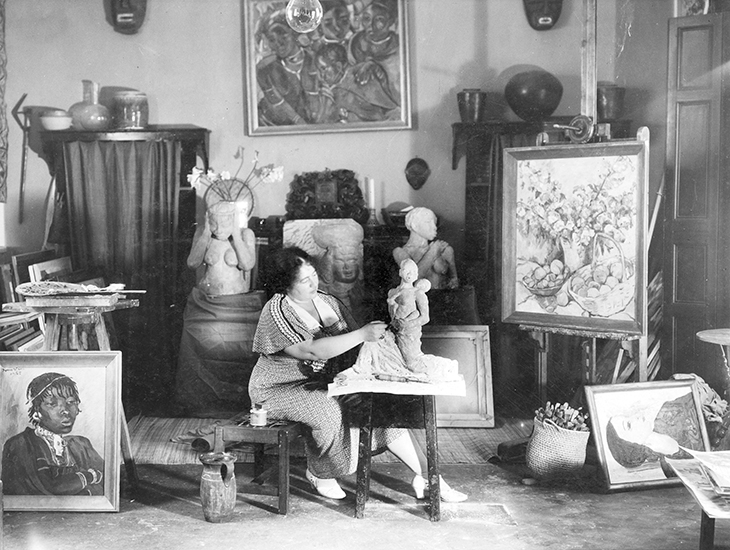

Irma Stern in Cape Town, circa early 1920s. National Library of South Africa

Stern was 27 when, in 1922, she was thrust into the spotlight with an exhibition in Cape Town that, in no small part, spelled the arrival of painterly modernism in South Africa. She sustained the public’s attention until her death in 1966. Along the way she developed from being a painter of genre scenes in the style of her mentor, the German expressionist painter Max Pechstein, into an assured colourist and adventurous travel painter. Throughout her life, she would recall her modest beginnings on a farm in a remote corner of the Transvaal Republic.

In 2015, curious to know more about the physical landscapes of Stern’s youth, I struck out north by car from Cape Town, where the artist lived from 1920 until her death in 1966. My destination was a dusty farming region bounded by the Vaal and Harts rivers in northwestern South Africa. Stern was born here, in the village of Schweizer-Reneke, in 1894, the first child of newly prosperous German-Jewish émigrés, Samuel and Hennie Stern. The Sterns owned a small trading business and a farm. Black farm labourers in the region, some of them likely sharecroppers, were important early companions for Irma.

A few months after the outbreak of the South African War (1899–1902), British forces occupied Schweizer-Reneke. Samuel was imprisoned for his Boer allegiances and the village razed. Stern’s rural youth lasted a mere six years. After a short stay in Cape Town, the Sterns moved to Germany. In 1909, the family briefly returned and settled in Wolmaransstad, a village neighbouring Schweizer-Reneke, but a year later they were back in Germany again. Irma settled in South Africa when she was 25. Her biographer Karel Schoeman described her in 1994 as a refugee; Stern frequently referred to herself as a ‘gypsy’. In an interview of 1931, she remarked that her upbringing had left her with ‘the feeling of belonging to nowhere’.

This feeling might account for Stern’s strong attachment to her farm beginnings. In 1927, when the influential Berlin art critic Max Osborn wrote Stern’s first monograph for Leipzig publisher Klinkhardt & Biermann, he reiterated the folksy claims Stern had made in her 1926 essay: ‘The little girl grew up, close to nature, in a region which would seem like a fairy story to us Europeans,’ writes Osborn. Written a decade after Pechstein’s travels to Palau in the Pacific, then a German colony, and inflected by Paul Gauguin’s much mythologised account of his time in French Polynesia in the 1890s, Osborn’s book presents Schweizer-Reneke as a place of strange animals and floral abundance. ‘Red lilies and light yellow blossoms could be plucked from thorn bushes. Insects and butterflies of strange forms and colours could be seen.’

This was not the landscape I found. Schweizer-Reneke is embattled, in common with much of the impoverished hinterland. The railway that once connected this region’s maize and beef farms to the economic centres in Kimberley and Johannesburg has collapsed. The contest over land, which was provisionally won in the early 1890s when white farmers established Schweizer-Reneke on the ruins of a stronghold used by the Korana chieftain David Mossweu, endures. This drought-prone region nonetheless has the power to surprise.

South Africa’s first people roamed this territory. Their art, rock engravings depicting wild animals and abstract forms, lies untended on uncultivated hillocks across the savannah – Stern preferred the word ‘steppe’. The artist credited the origins of her globe-spanning collection of votive and decorative objects from Africa, Asia, Europe and the Americas to the petroglyphs she found on her family farm. Some of these objects even featured alongside flower studies in her energetic still lifes and can be seen in her former home, now a museum, in Cape Town.

Irma Stern in her studio at The Firs, Cape Town, in 1936. National Library of South Africa

For the most part, art historians have repeated Stern’s folkloric recollections of her rural beginnings as fact. In my new book on Stern, I argue that it is important to look again at her early life, in particular the complicated social history of the region of her birth. Challenging the unreliable ways in which Stern remembered and narrated her farm upbringing opens up new ways of reading not only her early work, which strategically exaggerated her rural origins, but also the mature works from her South Africa years, especially the confident oils and drawings produced during and after her travels to Belgian Congo and Zanzibar in the period 1939 to 1946.

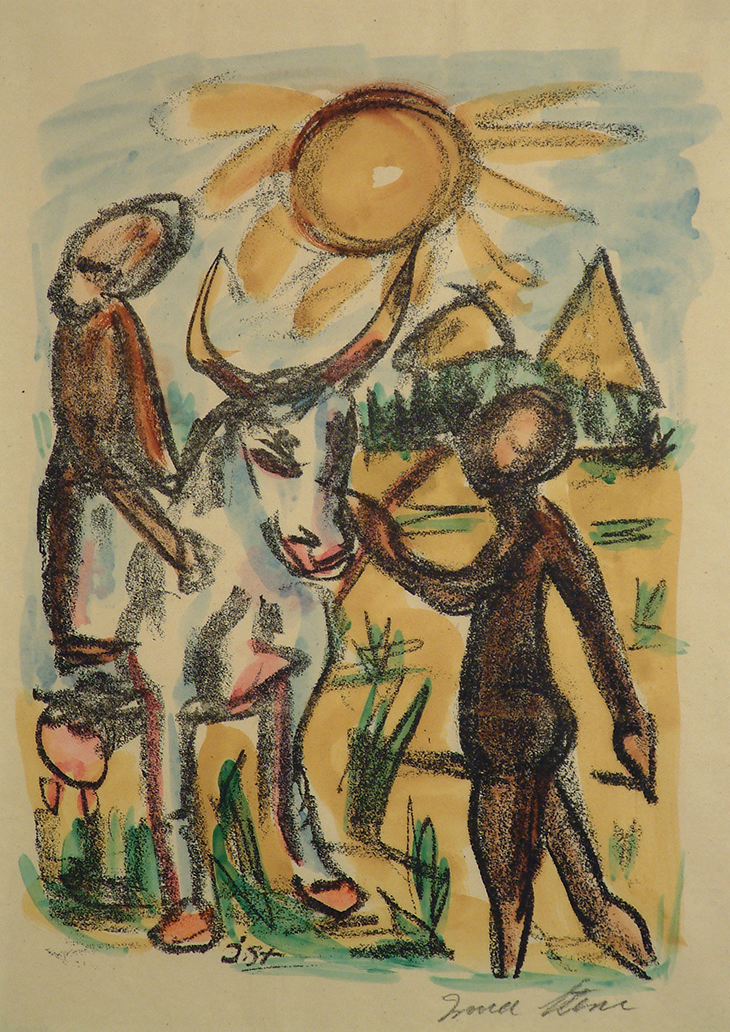

From Dumela Morena: Bilder aus Africa von Irma Stern (1920), Irma Stern

In 1920, the Berlin art dealer Wolfgang Gurlitt published Stern’s portfolio Dumela Morena: Bilder aus Africa von Irma Stern (the title translates from Tswana and German as ‘Hello Sir: Pictures Out of Africa by Irma Stern’). The portfolio comprises 11 prints depicting alternatively naked or loin-clothed black figures tending cattle, hunting, bearing wood, caring for children, dancing and relaxing in tropical landscapes. Stern’s near pagan worship of the sun is palpable in her naively ecstatic portrayal of her youthful home, as is Pechstein’s influence – but so too is the kind of racial stereotyping one finds in Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852), which Stern read in German translation.

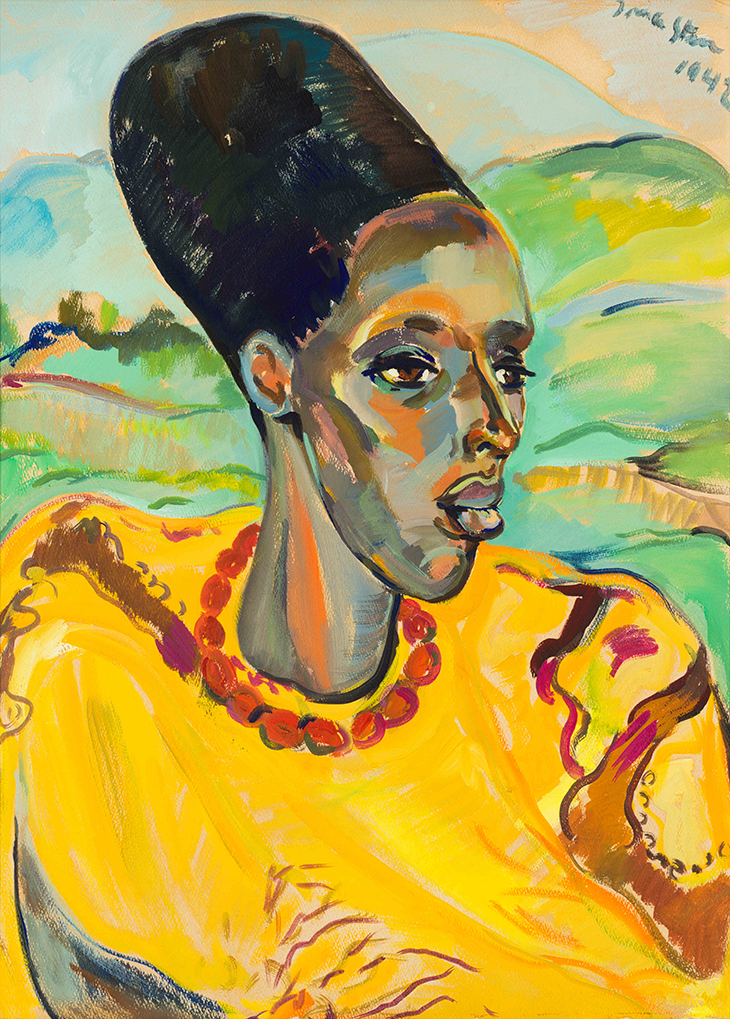

By 1942, when Stern made her first trip to the Belgian Congo, she had established herself as an audacious colourist working in descriptive expressionist style. Where her two Zanzibar journeys (1939 and 1945) enabled Stern to fully manifest her incipient orientalist inclinations as a painter, her Congo trip was, in certain respects, an attempt to reclaim the primitivist fantasies recorded in her earlier southern African work. Stern travelled by train with her car to Elizabethville (now Lubumbashi), in southern Congo, where she hired a local man, Pierre, as her chauffeur. Together they circumnavigated the entire Belgian colony, including present-day Rwanda.

Congo Woman (1942), Irma Stern. Private collection

The cultural rituals of Congo’s northeastern Mangbetu people, notably their head-binding practices, were of particular interest to Stern. First described by German botanist Georg Schweinfurth in 1870, these and other indigenous customs drew a steady stream of wealthy white tourists – among them painters, photographers and filmmakers – to the territory. Locals responded by making a show of their identities for visitors; Stern, for instance, stayed in a village whose leader, Chief Ekibondo, had transformed his settlement into a tourist attraction. She does not mention this experience in Congo (1943), a collectable artists’ book that juxtaposes travel vignettes with illustrations of her drawings and paintings.

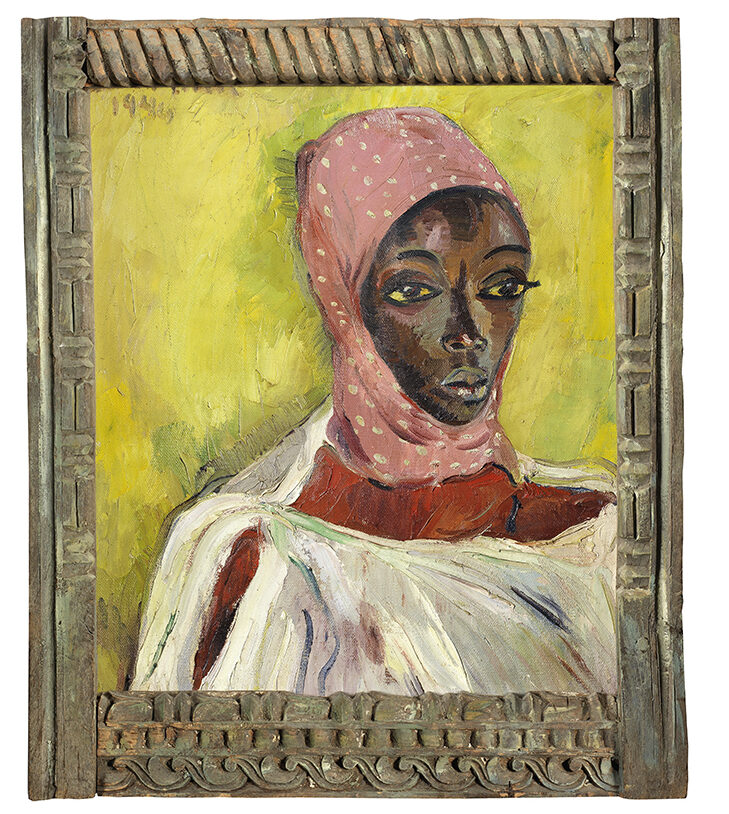

Watussi Chief’s Wife (1946), Irma Stern

Dispossession is a recurring and unsolved dilemma of African life. Stern’s realism, an important hallmark of her middle period, did not engage with this fact; her realism was purely formal, not social. Her work is largely silent about the context of colonisation, as well as its unravelling, which gained pace during her lifetime. Stern’s second visit to Belgian Congo in 1946 marked a turning point in her African adventurism. The trip was cut short by her contracting malaria. In correspondence with a friend she bemoaned the colony’s faltering colour bar and recounted being ‘surrounded by natives goggling at me’ when her car broke down. Stern the looker did not enjoy being looked at.

For her admirers, of which there are still many, as her recent auction prices attest to, this historical reckoning might be a source of discomfort. The unease is needed. The decorous formalism that has long been the focus of writing on Stern threatens to render her art a relic. Yet her life and work, mired as they are in complication, speak loudly to our contemporary moment.

Sean O’Toole’s Irma Stern: African in Europe – European in Africa is published by Prestel.