‘The Invention of Folk Art’ is the third and final exhibition in a series mounted by the Art of the Americas department at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, intended to shed light on ‘understudied works’ from the museum’s permanent collection. The exhibition is modestly scaled, housed in a single gallery in which curator Nonie Gadsden has presented thoughtful arrangements of two-dimensional works of art; a central vitrine for the display of books, sculptures, and archival video footage; and carefully crafted wall texts. ‘The Invention of Folk Art’ may occupy a small space, but it asks visitors to consider large questions about the structure of value in the art world, the mutual dependency between museums and collectors, and the role of museums in the 21st century.

The exhibition is anchored by works collected in the 1940s and ’50s by the opera singer Maxim Karolik, one of the museum’s benefactors. Karolik, along with his wife, Martha, was responsible for two other major collections that became the spine of the MFA’s holdings in American art: 18th- and 19th-century paintings, and furniture and decorative arts of the same period. The Karoliks’ acquisitions and philanthropy allowed the museum to compete with institutions such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York; the strategic partnership between the couple and the museum is revealed in the video of an interview with Maxim Karolik from 1962 that plays in the gallery. In addition to the conventionally prized works of American art – oil paintings by Thomas Sully (1783–1872) or Philadelphia furniture pieces by the mid 18th-century craftsman known as the Garvan carver – Karolik began seriously to collect what he referred to as ‘folk art’ in the 1940s.

At that point Karolik was, in fact, late to the game. Collectors, museums and artists had been studying, cataloguing and arguing over this ill-defined category of art for several decades. Holger Cahill curated an exhibition of American folk art at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1932–33 that consisted largely of the private collection of Abby Aldrich Rockefeller; and artists such as the painter and photographer Charles Sheeler and the sculptor Elie Nadelman were avid collectors throughout the 1920s and ’30s. If Karolik followed in the footsteps of this earlier coterie of American folk-art collectors, he was arguably path-breaking in bringing these works to the MFA and advocating for their inclusion in the permanent collection. At the time he did so, major institutions such as MoMA had formally declined gifts of folk art (Rockefeller’s collection ultimately became the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum in Williamsburg, Virginia).

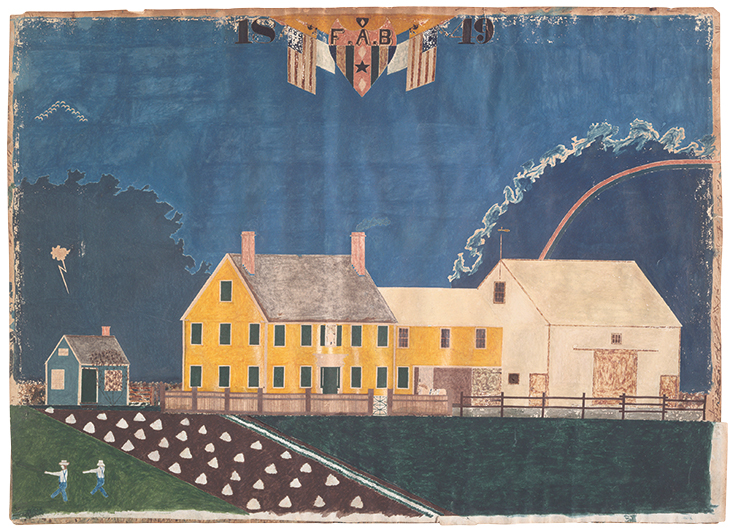

Farmstead in Passing Storm (1849), unidentified artist. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The Karolik folk art collection challenged the museum’s institutionalised writing of art history on multiple fronts. The work often had an untutored aesthetic sensibility, running counter to the standards of training and professionalisation that govern entry into the fine art canon. Often there was no record of the maker, which challenged the dominance of the brand-name artist. When Karolik did know the artist’s name, it was frequently a woman, or even a young girl – a fact that sat uneasily within the patriarchy of the acknowledged canon. Ultimately, much of this work embodied the visual culture of rural America, often working poor America, so did not harmonise with the vision of elite self-improvement represented in other parts of the museum’s collection. In ‘The Invention of Folk Art’, Gadsden suggests that Karolik’s folk art collection is notable for its ‘egalitarian’ embrace of visual art made in the United States in the 19th century.

At the same time, Karolik’s approach to what was called folk art in the early part of the 20th century is plagued by numerous biases, some of which the exhibition forthrightly calls out. The most notable bias is that, judging from what’s represented, Karolik collected objects made exclusively by white artists. ‘The Invention of Folk Art’ offers curatorial interventions that address the shortcomings of the collection, and the problematic nature of defining folk art overall. In a large section titled ‘Labels Matter’, Gadsden has included works by Latin American, Black, and Filipino-American artists from the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries that might be classified variously as ‘outsider’, ‘folk’, or ‘visionary’ art. In a separate section titled ‘So Many Stories’, the exhibition explores three works of art in the Karolik collection through their evolving reception history. The visitor is invited to flip through multiple pages of label text beneath each work and learn about why Karolik may have acquired the piece and how its meaning has changed in the 60 years since it entered the museum collection, and to read the views of scholars and contemporary artists about the work’s resonance today. While this section requires patience, the visitor is rewarded with a layered and complex view of the art.

Sarah Ann Drew (c. 1827), Ruth Whittier Shute. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The very concept of ‘folk art’ is, of course, fraught with difficulty. When it emerged as a collecting category about a century ago in the United States, it represented yet another pin on a mental map of alleged authenticity – alongside non-Western art and medieval art – constructed by modernists. In pursuit of expression that was somehow untainted by industrialisation and the commercial world, modernists celebrated the visual forms of cultures that they believed were ‘primitive’ and thus more truthful. In fact, the pieces on view in the exhibition include a fabulously detailed rendering of a world map made by a schoolgirl: the embodiment of education (as opposed to being ‘untutored’), and reflecting a curriculum that taught young minds the shape and scope of global reality. Folk art (or ‘outsider’ or ‘visionary’ art) has always been difficult to define in positive terms, and has been more readily understood as art in relation to to the canon of fine art (could we call the latter ‘insider’ art or ‘blind’ art?). ‘The Invention of Folk Art’ makes its boldest claim in a wall label that claims ‘all taste in art is a matter of opinion, and […] there are no right or wrong answers.’ This suggests that the spaces of the museum, governed as they are by the voices of collectors, history, and the canon, might begin to open up. When they do, we will see and hear more varied voices, whose modes of expression truly ask us to look differently and to learn more complex stories about the past.

‘Collecting Stories: The Invention of Folk Art’ is at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, until 9 January 2022.

From the June 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.