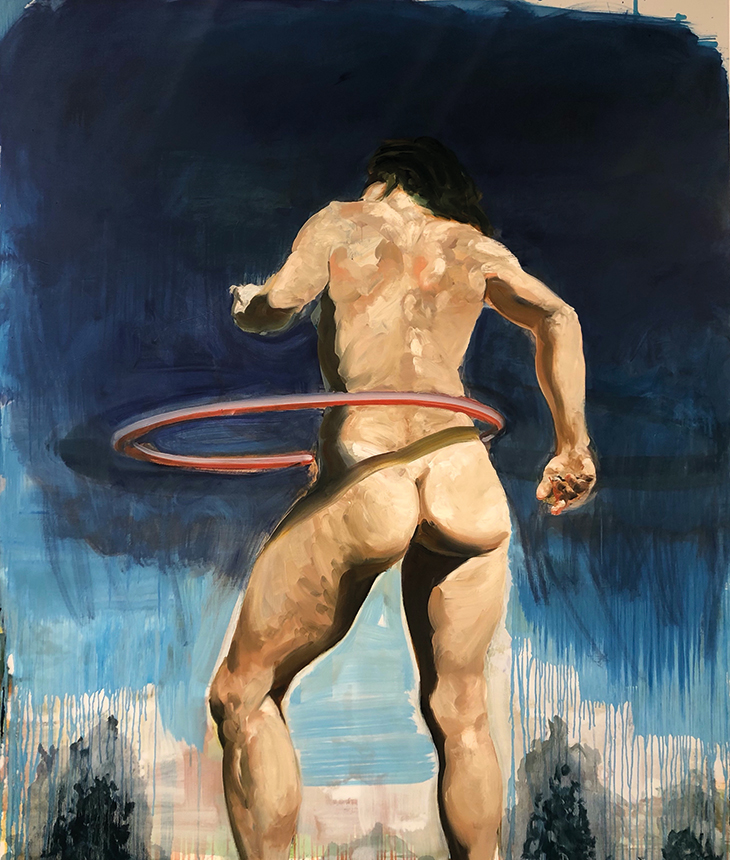

Behind Eric Fischl’s left shoulder, a young woman is twirling a red hula hoop around her bare waist. She is naked, her back and bum to the viewer, and frozen in a moment of athletic contrapposto, her balance affirmed by the clean horizontal of her hoop. This poise is precarious, though, as equilibrium in motion usually is, and the hoop also serves to emphasise movement. The image is made portentous by the dark skies that press on the figure’s leisure, as well as by our vantage point slightly below her, looking up. She is a colossus who might be on the cusp of tumbling over.

American Hula (2020), Eric Fischl. Courtesy the artist and Skarstedt, New York; © Eric Fischl/Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York

This is the protagonist of American Hula, a recent painting by Fischl that is still in his studio when we speak via video link in early June. ‘To be honest with you, it surprised me,’ he says of the work’s ominous timbre. ‘I came to accept it, and push it a little further in that direction. It was a painting that didn’t start out that way; it didn’t even start with that figure in it […] She comes from a photograph of a woman dancing.’ A second painting, also with a dark blue sky, stands on an easel beside Fischl. It depicts a young girl, naked on a vague shoreline, gesturing to a dog that seems undaunted by the vacancy of the scene (‘any painting that doesn’t have a dog in it is probably half a painting,’ he says jokingly). Fischl had been thinking about Lars Von Trier’s Melancholia (2011), he tells me, ‘the most apocalyptic movie you’ll ever see’, when he came to paint this scene of fading hopes and horizons. Its tragicomic title is Like Explaining the End of the World to a Dog.

For several months, Fischl has been sheltering in place at his home in Sag Harbor, Long Island, where he and his wife, the landscape painter April Gornik, have lived and worked since the 1990s. Perhaps it’s an effect of lockdown, but when Fischl appears on my screen he looks a little more rumpled than the suave, almost professorial figure familiar from portrait photographs; the video-call format gives prominence to his paint-streaked hands, while his silver hair has begun to light out at jaunty angles. But perhaps this is no more than the painter in his element, interrupted at work that right now feels obliquely attentive to the times. Recalling the events of 9/11 in his memoir, Bad Boy (2013), Fischl wrote that ‘it’s exactly in times of crisis that art is indispensable’; artists, he tells me, are ‘indispensable to society […] with their ability to organise chaotic stimulation into patterns of comprehensible meaningfulness’. Like Explaining the End of the World to a Dog, he explains, is a response to ‘where our trajectory is in terms of the environment,’ with ‘the facts, the science, set against the emotionalism, the stupidity or the greed of people – and also the fact that perhaps the most poignant message came from a 12-year-old [Greta Thunberg]’.

Self-Portrait: An Unfinished Work (2011), Eric Fischl Courtesy the artist and Skarstedt, New York; © Eric Fischl/Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York

More than any painter I’ve spoken to, perhaps, Fischl has an unwavering faith in his chosen medium and its possibilities; the process of painting, he says, is how painters ‘actually organise their feelings, thoughts, relationships to others’. This was not a belief inculcated in him as a young artist, but one that he had to discover for himself. Born in New York City in 1948, Fischl grew up in a suburban household on Long Island, studying at Arizona State University and then, after a speculative application was met by the offer of a full scholarship, enrolling at CalArts in Southern California. At the time, especially at the more radical art schools, painting was not so much taught as dismantled, a context in which Fischl presented abstract paintings that tended to dissatisfy him; all the same, contemporaries such as David Salle and Ross Bleckner would become lasting friends. Two years after graduating, and after a spell as a museum guard at the MCA Chicago, he took a teaching job at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design (NSCAD), Halifax, another school that was high on ideas and conceptual art. Was he was making a visual pun a few years later when, in Barbecue (1982), he painted two hapless fish in a bowl in front of a fire-breathing teenager? At the often anarchic art schools of the ’70s, he had felt, well, like a Fischl out of water. ‘When I started to paint the figure, I had to teach myself how to do it,’ he says. ‘I had to go back to the 19th century because that’s where we left it, back to the birth of modernism when artists had different strategies for breaking down the academic and reasserting certain things.’

It was in Canada, however, that Fischl hit on a technique that nudged open the door towards the narrative painting with which he would make his name. He began to paint figures and objects on sheets of glassine, a translucent paper that allowed him to layer multiple sheets, testing out the relationships between the elements he had depicted on each sheet and exploring how different arrangements might incubate tension or suspense. It was a method that was instrumental, albeit now as a preparatory technique, when he painted Sleepwalker (1979), the work that earned him instant notoriety when it was shown at the Edward Thorp Gallery, New York, in 1980. A study for the canvas, which shows an adolescent boy standing in a paddling pool at night while he masturbates, suggests how Fischl built up the image and its conundrums; two empty pool chairs perpendicular to one another on a first glassine sheet, then the pool on the next, placed in a quasi-filial relationship to the chairs, and finally the boy, shoulders hunched in concentration, on a third.

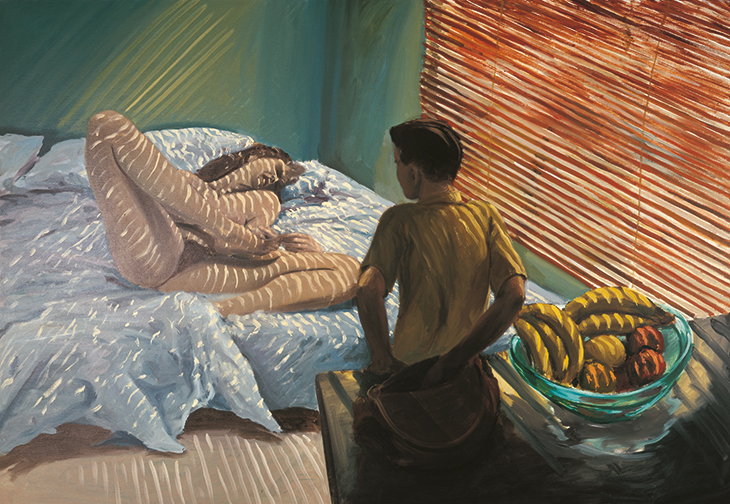

Bad Boy (1981), Eric Fischl. Courtesy the artist and Skarstedt, New York; © Eric Fischl/Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York

Sleepwalker was also one of the first large-scale oil paintings in which Fischl would find his natural idiom. Its provocative content, and that of works such as Bad Boy (1981) and Squirt (1982), was amplified by the artist’s brassy, even confrontational, embrace of figurative painting at a time when the traditional hierarchies of art had well and truly fractured. It was a period, Fischl recalls, in which the exploration and expression of personal identity across an array of media had become a type of orthodoxy: ‘One of the ironic things was the identity quest of a white, privileged, male painter,’ he says. ‘It’s a place where I found myself and thought, well, at least talk about what you know.’ By this time he had moved to New York, where Julian Schnabel, Salle and others had started to push painting back into fashion. Fischl’s reputation – and his prices – rose quickly; by 1986 he had an exhibition at the Whitney.

What Fischl knew, and what his paintings talked about, were the middle-class suburbs, with their social taboos, family secrets and fragile dreams of permanence. Fischl drew on difficult memories of his mother’s alcoholism and on the trauma of her suicide in 1970, confronting that event directly in A Funeral (1980), a grisaille panorama of his family gathered around the grave. Other works from the time explore suburban America through compositions as inscrutable as the milieu that inspired them. In Bad Boy, for example, a woman lies naked on an unmade bed in a shuttered room, her legs splayed; she surely cannot be asleep in that position, but she seems oblivious to the boy with his back to us, who watches her while he dips his hand into her purse. The painting includes many of the pictorial strategies that Fischl has frequently employed since in devising his finely balanced ambiguities: the suspended motion or gesture; the figure with its back turned, gaze and intention unknowable; the foregrounded objects, here the loaded fruit bowl, which may or may not be symbolic; the strong contrast of light and shade; the sharp crop; and the vulnerable naked body. The critic Martin Herbert, discussing a more recent body of paintings by Fischl, writes of the artist’s ‘complications of seeing’.

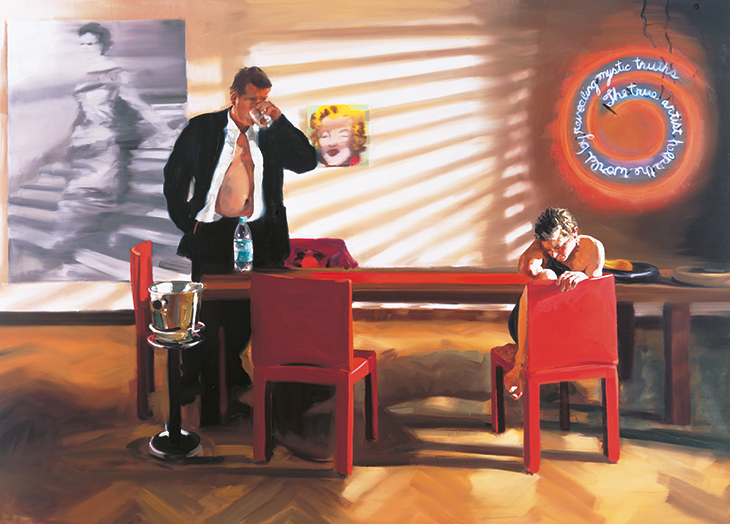

Krefeld Project; Dining Room, Scene #2 (2003), Eric Fischl. Courtesy the artist and Skarstedt, New York; © Eric Fischl/Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York

To this day, the process of painting for Fischl involves working towards such moments; his paintings are finished, paradoxically, when they convince him of the irresolvable mysteries of their content. He speaks of his process in terms of a conversation, of ‘questions’ and ‘intuitions’, that starts with him ‘talking to the painting’ which gives way, ‘hopefully’, to a point when ‘the painting begins to talk to you’ (he paints only one work at a time). ‘There’s a point at which you’re looking at a painting,’ he says, ‘and you’re no longer looking at it as the artist who made it, you’re no longer sitting there going, is that yellow too saturated, is this scale right. You’re looking at it thinking, what the fuck is going on here? Who are these people and what do they want? […] You’re now the viewer.’ The consummate expression of such enigmas, perhaps, is the Krefeld Project (2002–03), a suite of paintings that resulted from an invitation to make site-specific work for the Haus Esters, a villa designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe in Krefeld, Germany. Fischl installed two actors in the house, a man and a woman, photographing them in scenarios that imagined a fractious relationship between them; the resulting paintings, junctures in the life of a troubled marriage, are all the more evocative for eschewing sequential narrative – and yet they play on how far we rely on it to make sense of the world. For Fischl, as he has frequently said, ‘ambiguity is the essential quality of art’.

Fischl had turned increasingly to photography by the mid ’80s, no longer drawing primarily from memory for his source material, and having set aside his ‘received prejudice’ about the camera as a mechanical aid. He had been worried that the mediation of the photograph would undermine his conviction, inherited from the gestural credos of the Abstract Expressionists, ‘that execution and intention should happen simultaneously on the canvas’ (few painters have written, as Fischl does in Bad Boy, so frankly about the relationship between the artist and their brushstrokes). What he found, instead, was that photographs heightened his sense of the vulnerability of the human body in motion, that people were always ‘off balance […] starting to droop, starting to sit up, starting to turn’; when those isolated movements were transposed to the canvas, the body language of the figures seemed more indeterminable – or more open to interpretation – than ever. It’s in this context that Fischl justifies his attention on the naked figure, and particularly the female figure, which he has painted and sculpted persistently – sometimes in the face of criticism – throughout his career: ‘“Naked” to me is an emotional and psychological condition that manifests itself in exposure,’ he says, ‘and not the nude, which is something that is aesthetic, primarily an aesthetic appreciation of otherness.’

Bayonne (1985), Eric Fischl. Courtesy the artist and Skarstedt, New York; © Eric Fischl/Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York

The embrace of photography furthered an artistic approach that was already richly alert to the associative qualities of images. For all that Fischl is a determinedly gestural painter, an adherent of the brushstroke and its contingencies, since the glassine paintings of the late ’70s his work has also often moved forwards through collage-like techniques that have to differing degrees disclosed the constructed nature of narrative. ‘I look at it oftentimes embarrassingly,’ he says, ‘because I can see that I’m pushing [my work] into an overtly deconstructed painting form, and then pulling it back into a holistic format.’ In the mid ’80s he made a number of paintings on multiple canvases, some of which were cantilevered from the wall, denying the integrity that we usually anticipate in figurative scenes. His works on paper, including recent paintings shown this spring in ‘Figures’ at Skarstedt Gallery, London, frequently employ cut-outs in oil of men, women and children that have been fixed on a painted background, the conspicuous pinholes recapitulating the process of testing the relationships between figures in space.

Untitled (2019), Eric Fischl. Courtesy the artist and Skarstedt, New York; © Eric Fischl/Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York

Similarly, for his large-scale oil paintings, he experiments with figures and other elements using Photoshop, tweezering them in and, more often, out of place before he further transforms the composition on the canvas. ‘I can go through hundreds of ideas in a very short time,’ he says, ‘I can move figures in and out of a bedroom, I can enlarge them, shrink them, change what they’re looking at.’ Photoshop studies of Late America (2016), for instance, show how the central figure of the boy, and later his Stars and Stripes towel, were introduced into the arrangement while other figures and objects were excised.

Late America (2016), Eric Fischl. Courtesy the artist and Skarstedt, New York; © Eric Fischl/Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York

Late America, like Fischl’s other recent paintings set beside private pools or in luxury residences, makes few excuses for focusing on a world of privilege; the pair of faceless gardeners at work in the distance act like staffage in a 17th-century landscape painting, picturesque figures arranged symmetrically on the canvas as if to admit that, within the world of the painting, they have become no more than part of the scenery. But there is a scrutiny of American decadence here that has characterised much of Fischl’s work during the past decade, as he has explored the relentless assertion of privilege and how it contaminates the relationship between self and other. That includes his art fair paintings, in which the rarefied disarray of the art market is the subject of what are his most knowingly satirical works to date. Fischl has often spoken of his disaffection with the art world since the 1980s, with its shift towards speculation and the attendant compromise of artistic values, often while reflecting frankly on how his work fell out of fashion during the ’90s. ‘It became less about what the content was of the work and more about the look of the work,’ he says.

False Gods (2015), Eric Fischl. Courtesy the artist and Skarstedt, New York; © Eric Fischl/Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York

And that, perhaps, is why Fischl remains such an engaging outlier, with his feeling for narrative and the disruptions that can be exacted on it by paint, and with his enduring conviction that paintings might open up a space for us to better understand our relationship with the world. He is still making paintings that make demands of him, that talk back at him in the way that American Hula did: ‘They’re fundamental questions about my existence,’ he says, ‘that I keep trying to figure out answers to.’

From the July/August 2020 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.