The London-based artist Raqib Shaw uses enamel paints and a needle-sharp porcupine quill to create richly textured surfaces that glint with gold, rhinestones and glitter. Born in Calcutta into a family of merchants and raised in Kashmir, his work is influenced by his early memories of living with an eclectic collection of antiques, jewellery and fabrics. Shaw often draws inspiration from Eastern and Western mythologies, as well as Old Masters paintings. For his upcoming solo show at Ca’Pesaro in Venice, the artist has turned his eye to the Venetian masters, fashioning a new suite of vivid, opulent scenes that bring together biography and history.

Where is your studio?

My studio is in a former sausage factory in Peckham, South London.

What do you like most about the space?

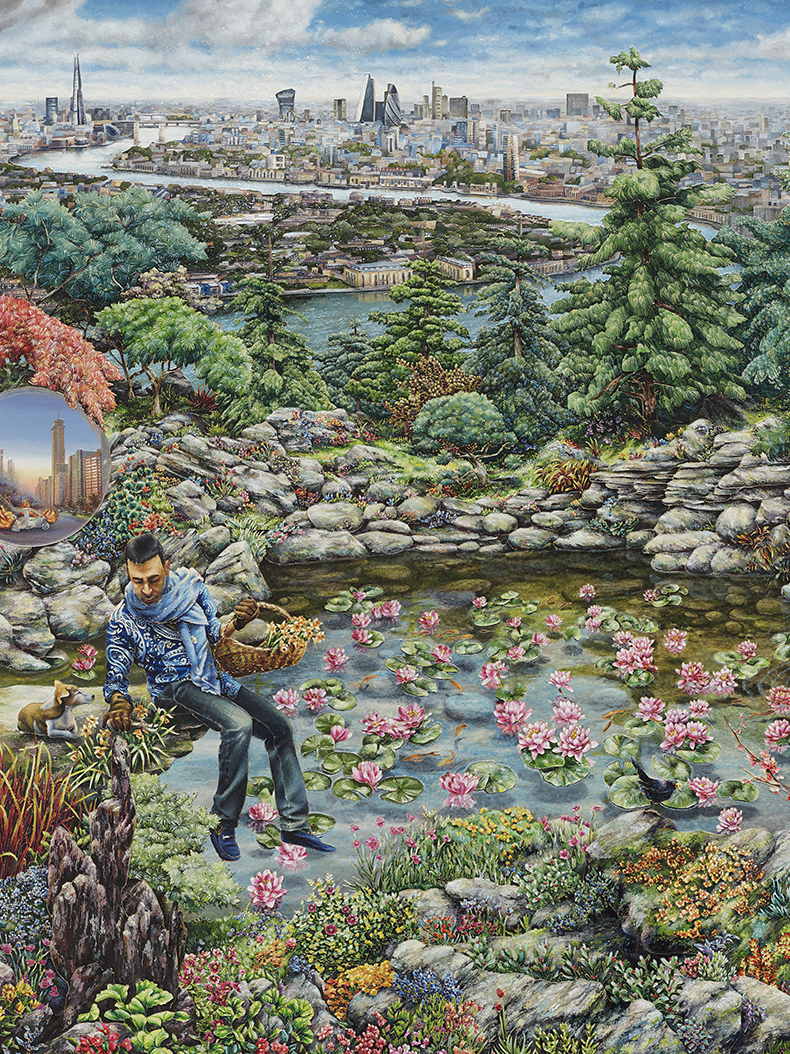

I like the fact that it is a bubble of peace, tranquility, nature and aesthetics in the middle of the busting metropolis.

What frustrates you about it?

I’m not frustrated about anything in life.

Do you work alone?

No, I have a wonderful team of assistants, most of whom have been with me for over a decade and a half now.

Photo: Joseph Sinclair

How messy is your studio?

Some areas are particularly neat and organised, but it tends to get messy when we are in the midst of an exhibition, and there’s usually an abundance of gardening tools lying around. I’m actually just about to start my next spring clean, I’m hoping to get rid of some old office files and accumulated furniture from days gone by — are you interested in an old Regency style porter’s chair by any chance?

What’s the weirdest object in there?

The ‘weirdest’ object in the studio has to be the small, rather realistic maquette of the Adam sculpture, depicting a sapphire encrusted lobster having sex with a bird-headed man, dribbling saliva — that or the coffin I used as a prop for a painting back in 2015.

Your work draws on a wide range of iconography – do you pin up images of other artist’s works on your walls?

Usually, there are images of Old Masters paintings pinned on the wall depending on who I am looking at. The image of Annibale Carracci’s Dead Christ Mourned from the National Gallery is always up — I simply love the composition, colour and emotion this masterwork.

Agony in the Garden (after Tintoretto) II (2020–2021), Raqib Shaw. Photo: White Cube (Ollie Hammick); courtesy the artist and White Cube

What’s the most well-thumbed book in your studio?

The most well-thumbed publication — to the extent that it is now almost in tatters — is my very first illustrated story book, Grimm’s Fairytales by Hamlyn, that I have had since the age of seven or eight.

Which artistic tool could you least do without?

Strangely enough, a porcupine quill.

Do you have several paintings on the go at once or do you tend to focus on one at a time?

That depends on the size — if the painting is large then there is no scope of working on others, but with smaller scale works, I usually work on compositions simultaneously.

Do you cook in the studio?

Nobody cooks in the working part of the studio. The smell of food would simply kill the mindset generated by the delicate fragrance of jasmine, gardenia and other seasonal blooms wafting gently through the windows.

The studio garden

What do you listen to while you’re working?

Lately, I have been enjoying silence and birdsong in the garden.

Do you ever sleep in your studio?

I live in my studio.

Who’s the most interesting visitor you’ve had to your studio?

Over the years, we have had some incredibly fascinating visitors. The most memorable in recent history, however, was when Reneé Fleming came for tea and I asked the resident pianist to start playing the opening notes to Dvorák’s Song to the Moon from Rusalka as she was leaving. She stopped and sang the beginning of what I consider her signature aria leaving me teary-eyed. It was simply unforgettable.

Is anything (or anyone) banned?

The studio seems to have its own mystic centrifugal system that spins out negativity of all kinds so there is no need to ban anything or anyone.

La Tempesta (after Giorgione) (2019–21), Raqib Shaw. Photo: White Cube (Ollie Hammick); courtesy the artist and White Cube

‘Raqib Shaw: Palazzo della Memoria’ is at Ca’Pesaro, Venice from 22 April until 25 September 2022.