Within minutes of entering R.H. Quaytman’s studio on the Lower East Side, New York, I am, at her invitation, putting my hands on one of the paintings on the wall to feel the strange, rough texture of the rabbit-skin glue gesso she’s been using for decades. ‘I wish I could let people touch it,’ she says of the works on public display. ‘Stroke it like a pet!’ She used to do that at Orchard, the Manhattan gallery space she ran with several other artists from 2005 until 2008, where she was given to such gestures of extreme intimacy or transparency – even the gallery’s finances became fodder for an artwork, in the form of a spreadsheet. ‘But now,’ she says, ‘the insurance is too intense’ to let anyone touch the works; the galleries ‘get so freaked out.’ She draws a much bigger crowd nowadays, for one thing.

Quaytman’s irreverence in the face of the artwork, and of the standard pieties of art criticism and the art market, has been earned over a lifetime. Born in 1961, she is the scion of writers and artists – her mother is the poet Susan Howe, her father was the abstract painter Harvey Quaytman, and her stepfather, the sculptor David von Schlegell – and has evidently had to shape a space for herself between the starry, larger-than-life 1960s and ’70s New York scene in which she grew up, and her own generation of visual artists, who often reacted in the other direction. She has described ‘the religion of my family’ as ‘minimalism with one foot stuck in modernism’, and she herself does not belong to that tradition, nor, quite, among those artists of the 1980s and ’90s who refused that quasi-religious attitude to abstraction and minimalism.

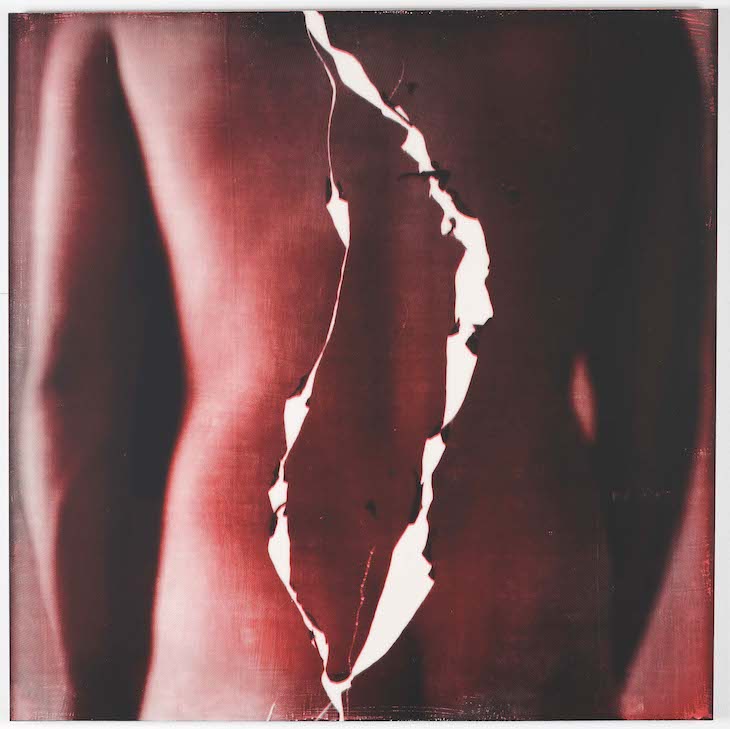

Beard, Chapter 19 (2010), R.H. Quaytman. Image courtesy the artist, Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York and Galerie Buchholz Berlin/Cologne/New York

Some of her contemporaries responded to the exhaustion of possibilities for authenticity and grand-narrative meaning with a retreat into melancholy and ironic prettiness. The young Quaytman, on the other hand, having intimately witnessed the way a rich artistic context could be reduced in retrospect to a few fetishised individuals, found the prospect of an apparent dead-end a bracing one: ‘It’s a good thing to be past the time of genius, the intuitive, and the heroic,’ she wrote in 2006 in an illuminating autobiographical essay (published in a 2008 book entitled Allegorical Decoys). If the death of the genius only excited her, so did the constantly threatened obsolescence of painting as a form (and later of photography, too). She studied painting as an undergraduate at Bard and spent a year at an art college in Dublin and later another in Paris, but she didn’t follow the MFA path. After working in the late ’80s as a curator and programme coordinator for the PS1 museum in Queens, where she began a long and passionate engagement with the work of the Swedish abstract painter Hilma af Klint, she undertook her formation as an artist in earnest during an intensely experimental 1991 fellowship year at the American Academy in Rome.

Over the following years, while omnivorous in terms of technique – making mirrored boxes and architectural models, photographing and silkscreening them, designing books – Quaytman developed an increasingly rigorous system for her work. She uses frameless wood panels with beveled edges, on which she paints the absorbent gesso of chalk and rabbit-skin glue, then unevenly sands it down and silkscreens photographic and other images on top. ‘I guess I do feel iconoclastic when it comes to the photograph,’ she tells me. ‘I want to take it down. And flatten it. And take its little magic thing out.’ (These silkscreened works are often interspersed with smaller handpainted ones, which sometimes depict arrows or other exhibition signage.) The rules she adheres to are strict: individual works come in a range of 10 specific sizes, either square or a golden-section rectangle, to be hung in relation to one another according to a precise and complex geometry. The pieces are made for particular sites where they will be exhibited, and they encompass a palimpsest of meanings and references (many rooted in the location), while also constantly denying their own depth – using the low-res effect of the silkscreening to deflect attention back to the picture surface, dazzling the eye with Op patterns or diamond dust, and implicating the viewer by formal tricks that often draw her imagined perspective and elements of the gallery space around her into the world of the painting itself.

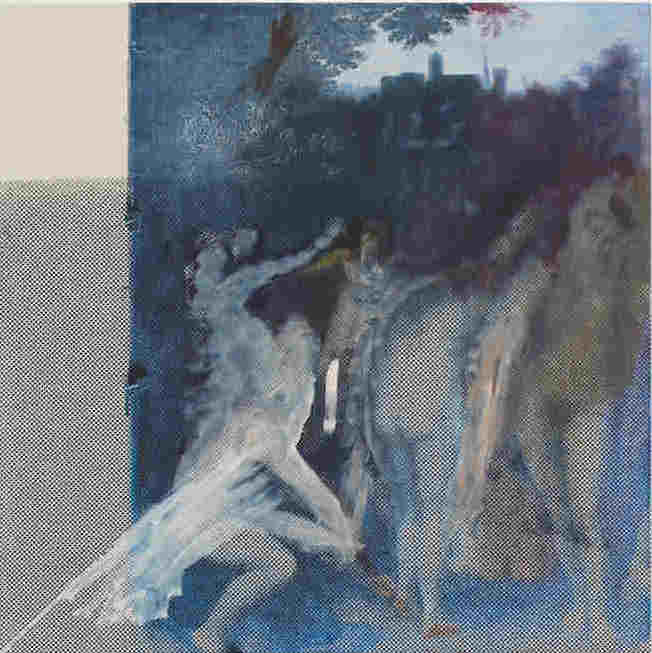

Ark, Chapter 10 (2008), R.H. Quaytman. Image courtesy the artist, Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York and Galerie Buchholz Berlin/Cologne/New York

In person, Quaytman is a disarming combination of seriousness and play. Her work seems driven by an earthy love of material and an urgent determination to solve a series of intellectual problems: first the question of how to make an abstract painting, then a knot of ideas about perspective she had to work through. ‘Usually there’d be just little things like putting the picture into perspective itself, thereby flattening it. You break your way out slowly. Or finding what information is hidden by the perspective of the photograph, and then trying to somehow emphasise that.’ Her influences are varied, from obvious pioneers of photography-based work such as Lichtenstein, Warhol, and Rauschenberg, to Hilma af Klint and less known figures like Anne Tyng or Dorothy Norman, or the Polish sculptor Katarzyna Kobro – an early inspiration whose Spatial Compositions were intended to burst their formal and physical bounds in a way similar to the effect Quaytman was striving for with her paintings.

The structure Quaytman has set for herself evolved in semi-private, although she had exhibitions from the late ’90s onward, becoming more visible after 2008, when major institutions such as the Whitney, MoMA, the Guggenheim, and Tate began acquiring her pieces. Long before that she had established a method of archiving and curating her own work, which since 2001 she has conceived as a series of interrelated ‘chapters’ in a partly imaginary book. We meet as she is ‘in the thick of it’ with the very latest instalment, ‘An Evening: Chapter 32’, which opens at the Secession in Vienna this month. The chapters are a characteristic gesture: modest and defiant at once. By shifting the emphasis from the individual painting to its neighbours and the surrounding environment, it pops the painting bubble, the aura of total self-sufficiency such art objects tend to project. ‘Haven’t you noticed paintings are very egotistical?’ she asks me. ‘I always felt that paintings had a lot of ego, not my paintings, necessarily, but paintings in general. Look at the rooms they’re in, the walls they’re on, the money they cost, the whole thing. The way they’re saved like nothing is saved. Really, they come through history in an amazing way.’ Her concern with how one painting in a space affects another is an attempt to ‘displace that ego, by making the painting be influenced somehow by what’s next to it’.

At the same time, the gesture insists that Quaytman’s entire body of work will retain its conceptual value and coherence regardless of the vagaries of the market or critical fashion. The notion of all of her work forming a continuous whole is one she took from Hilma af Klint, whose insistence on it (which extended to a refusal to sell any of her paintings) went so far as to help guarantee her own obscurity. Each exhibition Quaytman makes is a new chapter, recapitulating all of the previous pieces at least implicitly, and sometimes more literally, so that there is a sense both of permanence and constant reinterpretation. Unsold works are kept on special shelves, like books, and quite a few of them have a representation of their own bottom edge, the stripes of the wooden panel, included on the pictorial surface, a reference to their coming horizontal fate.

While we talk, Quaytman sits on her desk and smokes a cigarette, rifles through hand-altered books and polaroids and laughs her deep bubbling laugh. She is highly practical about everything from the reasons for her success to her own underlying motivations. She matter-of-factly recalls suffering ‘so much anxiety and sadness and depression over being unable to succeed, to make it or sell my work or get a show. I couldn’t even get a gallery. I couldn’t even get anybody over to my studio until finally Miguel [Abreu] agreed to come over one day.’ Her use of the chapter conceit she attributes both to a defence mechanism, a fighting back against the fear of failure – wanting to make it less ‘shameful’ not to sell and to end up, perforce, collecting a lot of her own old work – and to a desire to push back against the ‘egotism of my own paintings’. It is a philosophical experiment that also functions as a way to manage more worldly anxieties: ‘a way to sort of take charge of time’. She refers to it as a way of ‘keeping the power’, as she felt Hilma af Klint likewise did by treating all her work as part of a larger unit. Though it wasn’t her intention, Quaytman even suspects that the use of this system has been key to her increasing success over the last decade or so, ‘because you can fetishise it’ and there are ‘sub-categories that collectors can engage with’. Whatever the social or professional benefits of her system, it has also and much more importantly proved a generative artistic constraint.

One idea that subtly emerges over the course of our conversation is that of power struggle – including that which may take place between artist and viewer, artist and critic, artist and artist, and prior to all that, between artist and medium. Her use of the initials in place of her first names (Rebecca Howe) was an early attempt to deflect the tendency of both galleries and critics to emphasise the person over the paintings (especially in the case of a woman artist). She enjoyed how the genderless signage accompanying her work forced an avoidance of any concentration on the artist’s persona. She also liked getting early reviews in Europe that misgendered her: ‘It was fun that they assumed it was a he.’ Her choice of painting as a form is a bold and potentially fraught one, and that in itself provides the questions that guide her as a painter. She says she has tended to avoid the brush, since when you pick one up ‘you have to bring everybody with you…all the brushes start appearing.’ At this point in history, ‘I do believe it’s next to impossible to make a new mark.’

Nonetheless she has never once considered abandoning painting, ‘because I think it’s really the best problem in art. The plane, the picture, is the best, deepest problem.’ Photographs on the other hand strike her as almost too easy. ‘That’s sort of in a lockdown. Like, to me, every photograph is good. Every photograph does this incredible thing. Just by being a photograph.’ She prefers to paint on to a photography-based image – this is where new and strange formal challenges are still to be found. ‘It just seems open, as a way to rethink what to paint or how to paint.’ There appears to be a kind of loving aggression involved in the impulse: ‘I like the idea of painting on to a painting, or on to a photograph of a painting, being a way of looking at and thinking about it and digesting it, literally, taking it. I like that. It’s similar to touching a painting – a similar feeling.’

Installation view, ‘R.H. Quaytman, Morning: Chapter 30’, at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, 2016 Photo: Brian Forest; Courtesy the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles

The rules governing the dimensions of each piece and the spaces between them started out, like the chapters, in part as a self-protective measure: ‘My father’s work was often big canvases, these huge unruly things wrapped in plastic and bubble wrap and covered in dust and God knows what, and who will ever open it.’ Such fears have become less compelling over time, and not only about her own work – she’s excited about an upcoming show of her father’s paintings in Berkeley. But the commitment to making works whose ‘modularity’ makes them easier to store if not wanted has been freeing in other ways. You don’t have to make certain decisions or reinvent the wheel each time, and there’s a thematic or conceptual advantage too. ‘The internal geometry enables me to put very different images, very different pictorial ideas together. There’s another relationship between them that doesn’t have to depend on the logic of what the image is on the surface.’ What’s more, the move has always served to ‘take the pressure off the single image or the single event of the painting and displace it. In doing that, it questions all single paintings.’ A large survey show at MOCA in LA, which ran from last October until earlier this year, included a vast panorama of works referring to Michael Heizer’s land piece Double Negative, a progression of paintings placed in an unbroken horizontal line, whose shades gently shift.

This focus on relations between paintings over the individual works is reflected throughout Quaytman’s practice, which makes the curation of paintings into a form of sculpture or installation in its own right. ‘Oftentimes I’ll just come to a place with a pile of paintings I’ve made for that place, but I don’t know how I’m going to hang them.’ This will be true of her new chapter this November, and lends the prospect of that upcoming show an inherent anxiety that is familiar for Quaytman. Since her works are always to a greater or lesser degree developed with a particular environment in mind, approaching that environment with the works intended for it is always ‘really a scary moment’. She frequently makes changes to the paintings once they are in the space ‘to make them work in that way that I want them to’. With her paintings, she says, ‘the most fragile part of them is their combination’. The notion that this time the pieces may simply not hang together as she’d hoped is ‘the terror every time, that’s really the fucking thing that keeps me up at night. It’s terrifying. But I guess that it’s good to be a little bit worried. A lot worried!’

Amazons and Scythians (c. 1600), Otto van Veen (1556–1629). Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

On the walls of her studio are a series of works destined for the upcoming show at the Secession. The paintings are spurred by two late 16th-century panels by the Dutch artist Otto van Veen, best known as Rubens’ teacher, ‘and they love Rubens. They really do love him there.’ Quaytman is less keen (‘It’s just always so overt’) and prefers the teacher. Both paintings were found, badly damaged, in a stash of ‘weird leftover art’ on a ‘forgotten floor’ of Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum, which Quaytman describes as one of the world’s most amazing institutions, ‘like the Louvre without the crowds’. In exchange for helping fund the restoration, she was allowed to photograph the process and has been making works from that raw material. She shows me a lot of Polaroids (they’re ‘old now so you never know what the film is going to do, which I kind of like actually’), including one of the rugged-looking chief restorer, whose portrait she’s thinking of painting, and a range of other images that she then scans and silkscreens and paints on, or plays with by laying textiles on the exposure unit. There are pink infrared versions of the van Veen paintings, and works using only the marked backs of them. At the Secession, there are to be nine pictures on one wall and 13 on another, meeting in a narrow corner. ‘I have the two paintings coming together at this 45-degree vortex angle.’

The van Veen works are tableaux concerned with female power, one of them showing ‘the Amazons getting together with the Scythians’, whom they will eventually persuade to form a more equal society (travelling to Greece recently brought home to Quaytman that ‘the story of the Amazons is completely integral to the founding of democracy’). The other shows a group of Persian women as described in Plutarch, who refuse to let their men, in the midst of losing a battle, take refuge at home for the night – they fend them off with skirts lifted, exposing themselves, prompting the central male figure to fling his hands before his face and turn away along with his horse (‘the horse can’t even take it, the sight of that,’ Quaytman laughs). It’s a somewhat odd, jarring image – the composition of the landscape seeming to echo the V-shapes between the women’s thighs – but Quaytman diagnoses a fixation on female genitals that has a long history. ‘All the fabric and the cloth is always vaginal. The folds. They’re so focused on it throughout all Western art history. It’s one of the main focuses of accuracy and this weird sense of reality…When you think about it, it’s always a very, very important part of most pictures that have humans in them. The folds of what they’re wearing, the textiles.’ The fear of the vagina that’s dramatised in the van Veen painting comes along with the misogyny that she sees as a primary and fundamental problem structuring all our other problems. It’s also ‘crazy’: ‘I mean, the really hard thing to look at is a penis.’

An Evening, Chapter 32 (2017), R.H. Quaytman. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne/New York

An essay by the Austrian writer Elfriede Jelinek will accompany the works. Quaytman, though, is wary of ‘righteousness’ when dealing with the theme of the female warrior. ‘I’m concerned about a kind of shutdown if that becomes the main focus. I’m concerned that it becomes a licence for self-justification, for the painting’s ego.’ She even suggests that ‘the idea of one painting not being the painting is feminine. My idea of meaning being contingent on the neighbour, or the context, is a kind of feminine concept.’ In the sense that it’s associative? I ask. ‘Or boundless,’ she corrects me, ‘let’s put it that way.’ Hers is a feminism that encompasses Hilma af Klint and the ‘bafflement and terror of curators’ in the face of her work, ‘its being relegated always to mysticism, but not male artists that were doing exactly the same thing.’

‘Thinking about feminism has something to do with that picture for me,’ she continues, showing me an odd print thought to be from a lost Titian, with the same format as the Judgement of Paris. It shows Hecuba, mother of Paris, ‘who apparently had a dream before giving birth to him that she would give birth to a torch and it would set fire to Troy’. If feminism has something to do with the setting of fires, it’s no wonder Quaytman gleefully cites one of Terry Eagleton’s insights about Charlotte Brontë, whose novels she has loved since childhood – that ‘Charlotte in Jane Eyre, from being an unattractive, poor, powerless woman, is able to burn down the house, blind the man, and marry him.’ We agree that ‘that’s the dream!’ and she adds that with art, ‘that’s what in effect you can do.’ Perhaps, she says, ‘I’m just in my Amazon frame of mind lately. Working with these Amazons is making me think of battle. But also, our political reality.’

Morning, Chapter 30 (2016), R. H. Quaytman. Courtesy the artist, Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York and Galerie Buchholz Berlin/Cologne/New York

Quaytman has for a long time taken charge of the reading of her own work by means of her system and by publishing her own accounts of it. ‘The only control you have with interpretation is by writing. That’s so important.’ Here she gives me a mischievous look. ‘So you tell them what to say. And they say it.’ If anything, she says, critics will ‘get annoyed, often, by me over-explaining’. She’s always threatening to pre-empt their role altogether.

She has no interest in undermining the coherence of her project by ever giving up on the chapter structure. And yet, ‘I would like to get back to just the idea of painting one painting. Not groups. It could be one painting a chapter, or two. Ah, what a dream, that’d be so good! I really want to do that! I always thought the goal of the whole book thing would be to figure out how to make one painting.’ She’s laughing again: ‘In theory, the last chapter.’ The notion sounds like a lot of pressure, but she assures me that that’s always the very best way to keep herself engaged – ‘it’s drama, it’s good, it’s suspense.’

‘R.H. Quaytman: An Evening, Chapter 32’ is at the Secession, Vienna, from 17 November to 21 January 2018.

From the November 2018 issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here