This is a preview of Apollo Art Travel: Switzerland, published with the September issue of Apollo and the 24 September issue of the Spectator

Wandering around the brand new wing of Basel’s Kunstmuseum, it is easy to see why Switzerland’s art galleries are so renowned. The Kunstmuseum’s stately building now has a sleek extension – a serene and airy space, flooded with natural light. However this new wing, which opened in April 2016, is more than a superb example of sympathetic modern architecture. For Basel, and for Switzerland, it feels like a statement of intent. During the last century, Switzerland’s museums amassed wonderful arrays of modern art, but the galleries which housed them used to feel a little old-fashioned. That feeling is now firmly in the past. Now a host of new buildings, in cities all across the country, are giving these collections the stunning settings they deserve.

The architects of this extension, Emanuel Christ and Christoph Gantenbein, are based in Basel, a short stroll from the offices of Herzog & de Meuron, Switzerland’s most internationally renowned architects. Christ and Gantenbein are still only in their mid-40s (they are a generation younger than the architects of the Tate Modern conversion and its extension), and their work can be found all across Europe, yet most of their major buildings have been realised in Switzerland – most notably their bold, yet elegant extension to the Swiss National Museum in Zurich, which opened in July this year.

The Kunstmuseum Basel’s new extension, designed by the Swiss architects Christ & Gantenbein Photo: Julian Salinas/Kunstmuseum Basel

The Swiss National Museum isn’t the only museum in Zurich with ambitious expansion plans. In 2020, the Kunsthaus Zürich will unveil a spectacular new extension designed by the British architect David Chipperfield, who is best known for his sensitive rebuilding of the Neues Museum in Berlin. Zurich and Basel lead the way, but there are also important building projects in progress in Chur, Lausanne, and Bern. All across the country, Swiss museums are booming. Jaded business travellers may think of Switzerland as safe and sedate, but for artists and curators, indeed for anyone interested in art and culture, it has always been a hotbed of creativity. And now it has a range of museums to match.

Works by Alfred Böcklin (left and right) displayed in the Kunstmuseum Bern. Courtesy Kunstmuseum Bern

The building that began this recent architectural renaissance is the Fondation Beyeler, a tram ride from Basel’s Kunstmuseum, in a sleepy suburb near the German border. Within a tranquil garden concealed by a high wall is a sunlit pavilion designed by the architect Renzo Piano. This stark structure is an artwork in its own right, as well as an arcadia of modern art.

The Fondation Beyeler was the inspired creation of Ernst Beyeler, arguably the greatest art dealer of modern times and one of the co-founders of Art Basel. He started his career in the 1940s, in a small shop in Basel’s medieval old town, and over the next 50 years he acquired an amazing haul of modern art. In 1997 he opened the gallery to house his favourite paintings (there were a great many works he could never bear to sell), and during the last 20 years his suburban hideaway has become the most visited art museum in Switzerland. As soon as you step inside, you realise why. Beyeler didn’t buy in bulk, and he generally bought only established artists, but the paintings he bought were the very best. From the Monets and Cézannes to the Bacons and Warhols, every artwork you see here is a masterpiece. This focus on quality is reflected in every Swiss collection I’ve visited, but never more so than here.

The Zentrum Paul Klee in Bern, designed by Renzo Piano and opened in 2005 Switzerland Tourism/swiss-image.ch/Stephan Schacher

Renzo Piano was also responsible for another influential building that helped to inspire Switzerland’s current museum boom. On the green edge of Bern, Switzerland’s compact capital, the Zentrum Paul Klee, which opened in 2005, is a flowing glass-and-steel structure, which reflects Klee’s fascination with geometry and his debt to music. Containing a concert hall and artists’ studios, as well as exhibition spaces, this building showed Switzerland, and the wider world, that there were no limits to what an art gallery could be, inside or out.

The Zentrum Paul Klee houses the world’s biggest Klee collection (40 per cent of his oeuvre), and there are more works by the artist (and by many other modern masters) at the Kunstmuseum Bern, a grand old building in the centre of the city. Founded in 1879, it is one of Switzerland’s oldest art museums and its collection is jaw dropping. No wonder they’re building new galleries to be able display more of its collection. It holds some sublime Alpine landscapes by Ferdinand Hodler, a national figure in Switzerland, but a painter who is still comparatively unknown abroad. No one understood Switzerland’s lakes and mountains like Hodler, and it’s a revelation to see his work with the places he painted right outside. Other works in the collection demonstrate Switzerland’s role as a safe haven for radical artists. German Expressionist Ernst Ludwig Kirchner is best known for his paintings of Berlin and Dresden, but spent the last 20 years of his life in Davos, in the Swiss Alps. Bern has a fine selection of his Alpine paintings, which reveal a different side of this great artist.

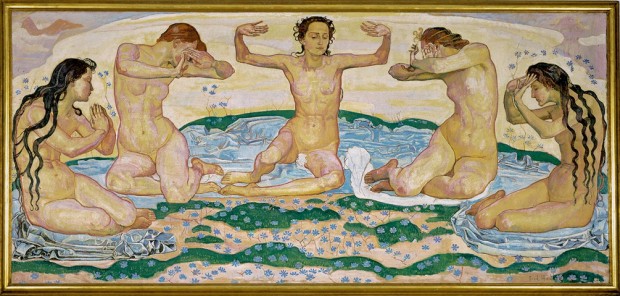

The Day (1899), Ferdinand Hodler. Courtesy Kunstmuseum Bern

What makes Switzerland’s art scene so special is that it isn’t dominated by a few museums. The Kunsthaus Zürich and Kunstmuseum Basel are the leading players, but they don’t overwhelm the artistic landscape. Unlike France or Britain, Switzerland has no dominant metropolis. Its 26 cantons are proudly independent – more like states than counties – and each aspires to have its own first-class art museum. Consequently, even small towns like Vevey on the north shore of Lake Geneva have significant collections. Solothurn in the northeast has barely 17,000 inhabitants, but its art gallery contains key works by Renoir, Degas, and Matisse.

Switzerland’s art scene has changed immensely since I started reporting from Switzerland 20 years ago, and nowhere sums up this change better than Lausanne. It has always been a striking city, perched above Lake Geneva, with breathtaking views over one of Western Europe’s largest lakes. Twenty years ago, it used to seem rather subdued. No longer. Lausanne has become the cultural hub of the Romandie (the French speaking part of Switzerland) and its thriving university gives it a lively, youthful ambience.

Lausanne’s cultural life is organic – it grows out of the people who live here – and now its institutions are catching up. For a century, the Musée cantonal des Beaux Arts (MCB-A) has been housed in Lausanne’s grandiose Palais de Rumine, alongside the canton’s zoological, geological, and archaeological museums. Despite its grandeur, this Belle Époque relic has insufficient space to show the MCB-A’s collection and many masterworks have been in storage for decades. Yet work is now underway on a new arts centre in the heart of this handsome city, which will unite fine art, applied art, and photography under one roof.

Platform 10 is the name of this new arts centre, and though it won’t open for several years, you get a great view of the building site as you pass through Lausanne by train. It’s located in the old sidings of the city’s central station, which is now just three and a half hours from Paris by TGV. In its new home the MCB-A will be able to display its splendid Hodlers and the world’s biggest collection of paintings by Félix Vallotton, who was born here in Lausanne.

Another museum that is relocating to Platform 10 is Lausanne’s excellent Musée de design et d’arts appliqués contemporains (MUDAC). For now, MUDAC is located in a historic townhouse beside the cathedral, at the summit of the old town. Platform 10 will give it room to grow, but its current home is intensely atmospheric, and even in this confined space there are many fascinating things to see. MUDAC explores the interface between applied and contemporary art – everything from plastic bags to Playmobil. It is more than a design museum: it is about the way we live today.

Untitled (1935–49), Auguste Forestier. Photo: Claude Bornard/Atelier de numérisation, Ville de Lausanne/Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne

My favourite museum in Switzerland is Lausanne’s Collection de l’Art Brut. Unlike the other museums mentioned here, nothing much has changed here in recent years. The term Art Brut was coined by the French artist Jean Dubuffet, to describe art made by loners and losers, people outside the art establishment. Dubuffet was an avid collector of ‘outsider’ art, and in 1971 he gave his collection to Lausanne. Much of it was made by people in psychiatric institutions; some of it was simply made by people in dead-end jobs, kept hidden from the world until they died. Some of it is disturbing, all of it is riveting. It’s honest and uninhibited, everything modern art ought to be. For me, it sums up everything that’s best about the Swiss art scene. Superficially, Switzerland may seem staid and conventional – but if you look closer, you realise that it’s at the very centre of the European avant-garde.

This is a preview of Apollo Art Travel: Switzerland, published with the September issue of Apollo and the 24 September issue of the Spectator