In William Roberts’ depiction of The Vorticists at the Restaurant de la Tour Eiffel: Spring 1915 (1961–62), the group’s only two female members – Jessica Dismorr and Helen Saunders – enter from the periphery of an open door. Saunders, a pale, hunched figure, glances tentatively into the room, where the men are already seated and the drinks have already been served. Intended as a riposte to Wyndham Lewis’s claims to sole ownership of the Vorticist movement, the painting is itself fairly unsubtle in its portrayal of the women as marginal. ‘Helen Saunders: Modernist Rebel’ at the Courtauld is a welcome corrective that also hints at the various ways in which the door did not stay open for long.

In spring 1915, the heyday of Vorticism was not far off, and neither was its decline. Intending to plunge ‘into the heart of the Present’ (as Lewis wrote in his manifesto) with a ‘New Living Abstraction’, the group were, for a brief moment, Britain’s best avant-garde hope, but the movement did not survive the First World War. Saunders showed six works in the group’s only London exhibition that summer and contributed both a poem and an illustration to the second (and last) issue of BLAST magazine, putting her firmly in the vanguard of British modernism.

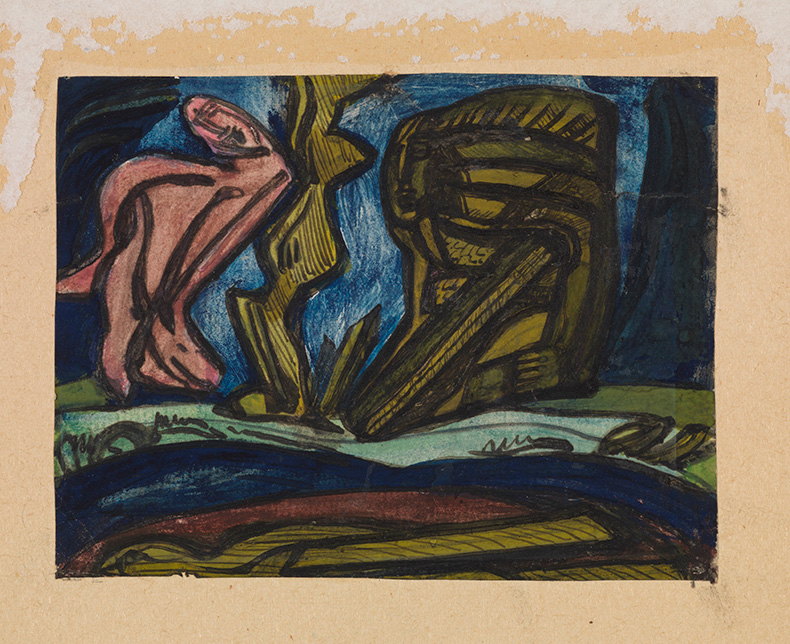

Untitled (‘The Rock Driller’) (c. 1913), Helen Saunders. Courtesy the Courtauld Gallery, London (Samuel Courtauld

Trust); © Estate of Helen Saunders

Few of the 18 works in the Courtauld show are entirely abstract. Figuration, and especially the female form, recurs. Vorticism celebrated the pace and promise of the world of machines – Saunders’ work often takes on subject matter favoured by her male contemporaries in ways that seem to take note of the winds of social change and political violence as they related to women. In Untitled (‘The Rock Driller’), for example, the labourer is in a dark green crouch – a reptilian cross between William Blake’s Newton and his Nebuchadnezzar – while a lithe pink nude seems free and mobile in comparison.

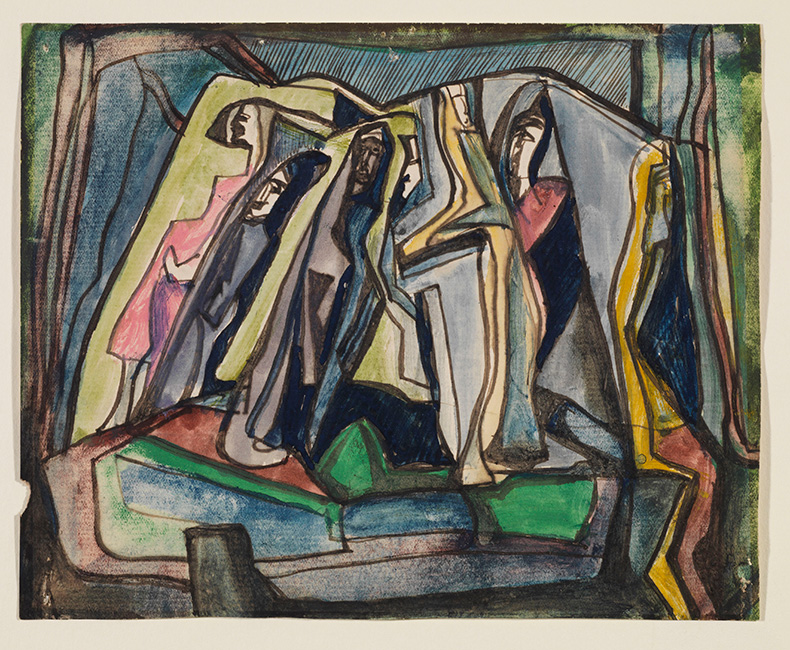

But then there’s Hammock (c. 1913–14), an agonised image appropriate for a world where women were being force-fed for seeking suffrage. Its weeping female figure is suspended, the curators note, from a frame reminiscent of a Queen Anne chair: what better symbol for the prison of the bourgeois home? Someone (not Saunders) has given a small, claustrophobic watercolour the title Female figures imprisoned (c. 1913). It’s a strange, troubling picture. Blake comes to mind again, not least because of the way the scale of the work invites scrutiny, pulling you in to peer at figures bent painfully out of shape in some subterranean space. Several of them are swathed in a royal blue, like Madonnas confined to ill-fitting niches.

Untitled (Female figures imprisoned) (c. 1913), Helen Saunders. Courtesy the Courtauld Gallery, London (Samuel Courtauld Trust); © Estate of Helen Saunders

Colour, used in bright, unexpected ways, is a hallmark of Saunders’ Vorticist period. There are stripes of grass green and pink; a minty wash behind jaunty double bass players in Cabaret; a river of yellow in a Vorticist composition of c. 1915. In a stand-out picture (also from c. 1915), an angular flesh-toned sprinter blasts out of a rifle butt, bolting towards a shard of sky blue. It isn’t quite the swimmer ‘into cleanness leaping’ anticipated from war by Rupert Brooke, but it does have all the hard-edged force of Vorticist work that violently rejected the old world in search of the new.

Saunders began looking in a less radical artistic direction even before the war, which had thrown such enthusiasms into question, ended; she soon faded from critical view. Though they had been friends and collaborators for years, Lewis broke with her in 1919 and she thereafter avoided the kinds of artistic networks that can nurture careers. It’s unclear how much of the work on display is actually finished and that, as well as the fact that all of Saunders’ Vorticist oil paintings are lost, makes her full contribution to the movement difficult to judge. One of her paintings was in fact recently identified – discovered beneath a portrait by Lewis. An extraordinary coda to the exhibition displays his celebrated Praxitella alongside an X-ray revealing him to have painted over Saunders’ Atlantic City, which appeared in the daring 1915 Vorticist exhibition. There is also a partial colour reconstruction that suggests the lost work as a bold evocation of the rush and vibrancy and sensory overload of urban life. Another deeply symbolic record of one woman’s erasure, it is also a tantalising glimpse of her spirited embrace of modernity.

Vorticist composition (Black and Khaki) (c. 1915), Helen Saunders. Courtesy the Courtauld Gallery, London (Samuel Courtauld Trust); © Estate of Helen Saunders

‘Helen Saunders: Modernist Rebel’ is at the Courtauld Gallery, London, until 29 January 2023.