‘Let us not offend Boccioni with a funeral eulogy.’ This is how F.T. Marinetti, leader of the Futurist movement, began his introduction to the retrospective exhibition commemorating the death of the artist Umberto Boccioni (1882–1916). Italy’s avant-garde famously favoured the living over the dead and Marinetti recognised the tragic irony of the situation. His founding manifesto had called for its artists to be thrown into the wastebasket at the age of 40. Boccioni died at just 33. His life was cut short in the First World War; his loss fulfilled the Futurist ideologies of the glorification of war and constant artistic revolution, but robbed the movement of its most esteemed artist and aesthetic theorist. Centenaries tend to memorialise births, but Boccioni’s mythology owes much to his early death.

Boccioni was not the only artist casualty of the war – his Futurist colleague Antonio Sant’Elia, and fellow modernists Henri Gaudier-Brzeska and Franz Marc all died at the front. Following a stint in the Volunteer Cyclists’ Battalion when Italy first entered the war, in July 1916 Boccioni joined the field artillery. Offered release, he was determined to remain a soldier, and actively sought a place at the front, although his superiors told him ‘not to force his destiny’. The circumstances of Boccioni’s fate are less Futurist than one might imagine. During cavalry exercises on 16 August his horse was spooked by a lorry and bolted. Boccioni fell and was dragged by the horse, suffering severe injuries and dying only the following day. Throughout his career Boccioni had painted horses and it is a cruel irony that, having named his steed Vermiglia after the flaming red beast in the centre of The City Rises (1910), his fall would imitate the scene of what has become his most famous painting.

Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (1913), Umberto Boccioni. Museo del Novecento, Milan

The City Rises represents much more than the tragic end of Boccioni’s life. It epitomises the artist’s desire to paint Milan’s metamorphosis into modernity, expressed in the ‘Manifesto of Futurist Painters’ (1910), and his formula for doing so, described in the same year in the ‘Technical Manifesto of Futurist Painting’. Dissolution of ‘the opacity of bodies’ into light and colour is fused with deconstruction of space to ‘put the spectator in the centre of the picture’, and dynamic curves and straight-lines render universal dynamism as ‘dynamic sensation’. The painting’s illustration of Futurist theories is one of the many reasons it, and Boccioni’s career at large, has come to dominate the history of Futurism, as presented in museums, academic art history, and beyond.

Yet this canvas also shows how easily Boccioni’s early demise could have led to his being lost to history. The City Rises languished in the storeroom of the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna in Rome in the 1940s. The Italian state decided not to purchase it, judging the painting ‘of scant interest in the history of the movement’. Instead the Museum of Modern Art in New York acquired it in 1951, giving the painting, and Boccioni, a prominent place in the modernist canon. Such acquisitions have been crucial to the shaping of Boccioni’s posthumous reputation, in combination with the lessened association with Fascism, and melancholic biography befitting an avant-garde artist, both results of his premature death.

Boccioni’s life did not want for drama and romance, even before the artist’s allegiance to the avant-garde. His early years were defined by nomadism, from a childhood following his parents across the newly-unified Italy, to a youthful quest for artistic inspiration. Born in Reggio Calabria in 1882 to parents from the Romagna in northern Italy, the young Boccioni moved to Forlì, Genoa and then Padua. He attended technical college in Catania and moved to Rome to train as an artist in 1899, entering the studio of Giacomo Balla in 1902. Following four years’ training he went first to Paris, then spent a period in Russia – where he purportedly fathered an illegitimate son – returning via Warsaw and Vienna, before moving on to Padua, then Venice. His itinerant years concluded in August 1907 when he moved to Milan, home of many of Balla’s Divisionist colleagues, and, of course, the poet F.T. Marinetti.

Self-portrait (1909), Umberto Boccioni. Civico Gabinetto dei Disegno del Castello Sforzesco, Milan

In the absence of an autobiography, his unpublished writings from these early years offer glimpses into the internal life of an artist whose grand ambition was matched only by his self-doubt. In his 1907 diary Boccioni recorded his creative struggle and insecurity: ‘I must confess that I seek, seek, seek – and find nothing. Will I ever? Yesterday I was tired of the big city, today I desire it with all my heart. Tomorrow, what will I want?’ His self-examining tendencies take visual form in his self-portraits. In an example from 1909 his brooding expression is animated by the lightest strokes of pink pastels on his lips, yet remains indifferent to the drip of tempera over his left eye.

In 1910 Boccioni met Marinetti and, aggravated by the lack of attention received by young artists in Italy, joined his fledgling Futurist movement alongside the painters Carlo Carrà and Luigi Russolo. Over the next six years Boccioni developed Futurist art in painting, sculpture, and theory, held exhibitions throughout Europe and participated in Futurist performances. He also penned, with his collaborators and independently, numerous manifestos, and articles, and in 1914 his theoretical book Futurist Painting Sculpture (Plastic Dynamism). Other actions reveal a fiery temper. When the Futurists travelled to Florence in 1911 to chastise the critic and painter Ardengo Soffici for his review of their exhibition, Boccioni threw a punch. His passions were political as well as artistic; in September 1914 Boccioni was arrested with Marinetti for ripping up an Austrian flag in Milan’s Teatro Dal Verme, an act symbolising the movement’s interventionism and desire to side with the Allies. Marinetti’s recollections of Boccioni also reverberate with his ‘divine gaiety’. In 1913 he improvised a lecture in French for the assembled Parisian avant-garde at his sculpture exhibition; he did not speak French.

The Dream (1908-09), Umberto Boccioni. Private collection

Boccioni is also widely recognised as a sensitive soul due to the innumerable depictions of his mother, made throughout his life. Such works, most notably the imposing Materia (1912–13), as well as the psychological drama of his personal writings, have elicited psychological, as well as art-historical analysis. His affection for his mother and sister were never matched by a romantic relationship. His last love affair, with the Princess Vittoria Colonna (a distant relative of Michelangelo’s friend of the same name), was cut short by his death. He died with a letter from her in his pocket, and had written to her before the accident. Distressed at having not heard from her, he wrote, ‘I haven’t even the strength to stay on my horse.’

The image created by such biographical anecdotes, Boccioni’s ruminating self-portraits, and the artistic and personal anxieties of his diaries and letters, which are peppered with suicidal thoughts, befit the trope of the troubled and short-lived avant-garde artist, which from Vincent Van Gogh and Amedeo Modigliani, through the Abstract Expressionists, became prevalent in 20th-century art historiography.

After Boccioni’s death, biography, attribution, and the relationship between his art and writings have all remained central to Boccioni’s reception, as evident in the three publications marking the event. Gino Agnese’s new biography of the artist is his third in 20 years. A new edition of the catalogue raisonné by veteran Italian art historian Maurizio Calvesi and Alberto Dambruoso will add a number of works to the artist’s oeuvre. And, finally, the first English-language translation of his theoretical text Futurist Painting Sculpture (Plastic Dynamism), with an introduction by Maria Elena Versari, who translated the text with Richard Shane Agin, will allow the scope and profundity of Boccioni’s theoretical writings, beyond the well-known manifestos, to be acknowledged more internationally.

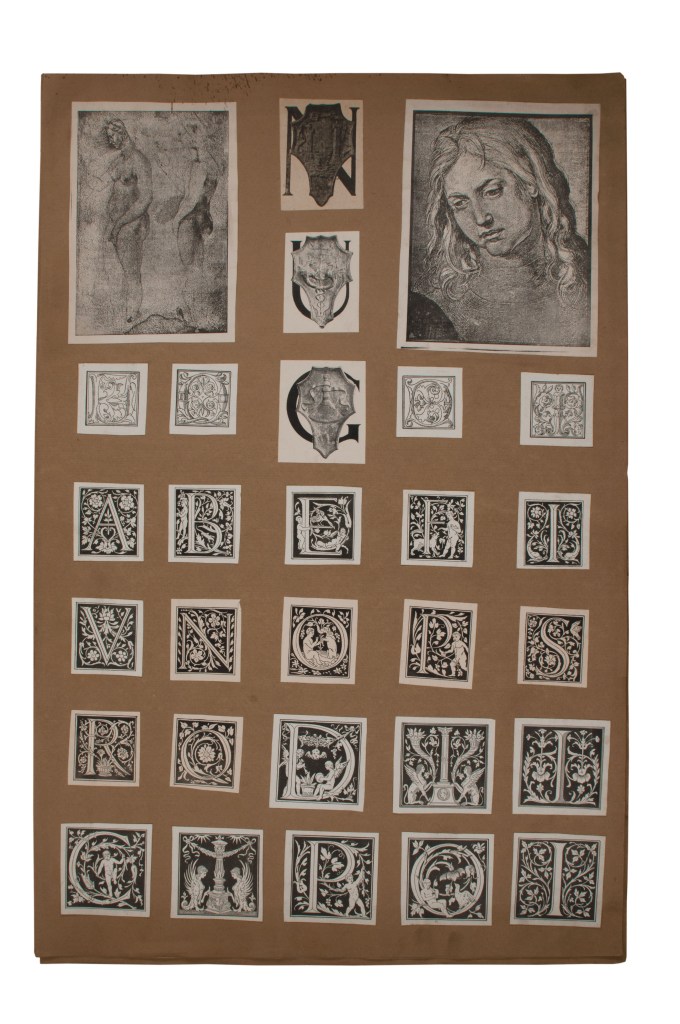

Page from Umberto Boccioni’s Atlas of Images (1895–1909). Biblioteca Civica, Fondo Callegari-Boccioni, Verona

The centenary retrospective at Milan’s Palazzo Reale (until 10 July) – a rare chance to see the city’s extraordinary collections of works on paper with numerous loans – seeks to situate Boccioni among his influences and contemporaries, almost to the point of dilution. Dividing his career in two, the pre-Futurist section focuses on the recently rediscovered scrapbook of around 200 images the young Boccioni clipped from books, and collected as postcards, from around 1895 to 1909. Dubbed a ‘Memory Atlas’ by the curators (in homage to Aby Warburg), it reveals the diversity of the young artist’s interests from Albrecht Dürer to Anders Zorn. In his diaries Boccioni fears being dwarfed by his artistic heroes, but here his early Symbolist paintings, such as The Dream (1908–09) hold their own against the larger canvases of his Divisionist predecessors Giovanni Segantini and Gaetano Previati.

Despite the clear formal ties between these artists’ depictions of horses and The City Rises (a notable absence from the exhibition), the show disconnects this formation from the Futurist years. Notwithstanding Futurism’s iconoclastic rhetoric, Boccioni drew parallels with his predecessors throughout his career, and even mapped Futurism’s place as the zenith of art’s history in his book Futurist Painting Sculpture (Plastic Dynamism). The presence of works in the later section by Boccioni’s avant-garde colleagues and competitors – for example, the face-off between Antigraceful (1913) and Medardo Rosso’s Madame Noblet (1897) – speaks not of Boccioni as a derivative artist, but as one who continued to subsume the approaches of others into his own style, when it suited him.

Antigraceful (1913, cast 1950). Umberto Boccioni. The Metropolitan Museum of New York.

The final pictures in the exhibition, from 1916, show his growing interest in Paul Cézanne, as his objectives developed. The imposing portrait of Ferruccio Busoni, painted at Pallanza in the months prior to his joining the field artillery, owes more to the solidity and stasis of the French Post-Impressionist than the frenetic whirl of his paintings in preceding years. This is perhaps most apparent in Interior with Two Female Figures (1916), a rarely-studied pencil, ink, watercolour and tempera work, which seems to pay homage both to Cézanne’s portraits of his wife and his watercolours. These later works still explore the relationship between figure and environment so important to Boccioni’s Futurist painting, sculpture, and writings, but with the focus on dynamism shifted to one of stasis.

Of course at the time of their creation, these were not Boccioni’s late works. They were potentially the beginning of a new phase of the artist’s mature work, which could have seen him, like Severini and Carrà, move further away from the dogma of Futurist dynamism, to a more classicising style. Yet there has been little hypothesising about where this metamorphosis would have taken him. Boccioni’s death allowed him to remain forever frozen as the hero of early Futurism, never tarnished by the brush of Fascism.

The dissolution of the Futurist activities by Severini and Carrà, along with the deaths of Boccioni and Sant’Elia, have led to 1916 being seen as the end of Futurist art. It is now well known that Marinetti continued the movement, with Balla and many new recruits, creating ‘Second Futurism’. Marinetti’s entrance into the Fascist Accademia allowed him to ensure that his movement survived under the regime. He also sought to preserve Boccioni’s reputation through retrospectives in Milan in 1924, as part of the Rome Biennale in 1925 and a major show at the Castello Sforzesco in 1933, and an edition of his writings in 1927. A number of Boccioni’s key works were acquired by the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna in Rome and the Podestà di Milano. The latter declined to pay for a nucleus of Boccioni works belonging to the recently deceased Futurist aviator Fedele Azari, so instead it was donated by Ausonio Canavese, a Turinese collector who hoped to be decorated for the gift.

Interior with Two Female Figures (1916), Umberto Boccioni. Civico Gabinetto dei Designi, Castello Sforesco, Milan

After the Second World War and the fall of Fascism, Futurism suffered a damnatio memoriae and in Italy Boccioni’s reputation flagged. In the United States, however, Boccioni was seen as a Futurist artist unsullied by the negative associations of his colleagues. He was by far the most represented artist in the Museum of Modern Art’s 1949 ‘Twentieth-Century Italian Art’ exhibition, and the museum went on to collect an important nucleus of his Futurist paintings and give them a prominent position in their canonical story of modern art. Marianne Martin’s judgement in 1958 is indicative of American attitudes in the post-war period: ‘It is Boccioni who, more than the other members, characterises the positive achievements of Futurism.’

Martin was writing for a catalogue of Boccioni drawings and prints from the collection of Harry and Lydia Winston – the Detroit-based collectors who, alongside MoMA, played a major role in Boccioni’s American fame. They regularly exhibited their collection of nearly 200 works on paper, mostly acquired directly from the artist’s sister, three posthumous bronze casts of Boccioni’s surviving plaster sculptures, and two paintings, across the United States, and in 1989 Lydia Winston Malbin donated much of her collection to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

It is, however, the sculpture Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (1913) that most clearly shows how Boccioni’s death has seen his star fall and rise. The work is one of only a handful of Boccioni’s sculptures to survive after the majority were deliberately destroyed in 1927. Piero da Verona, the sculptor who had kept the 10 or so unsold plaster and mixed-media works in his studio or warehouse, had his assistant destroy and discard them. Marco Bisi, the son of Boccioni’s second cousin, the painter Adriana Bisi Fabbri, heard of this destruction and managed to retrieve and reassemble parts of the red version of Development of a Bottle in Space (1913). The first publicly exhibited still-life sculpture, Boccioni’s Bottle was a landmark in later developments in the use of objects in sculpture. Yet Unique Forms has become the icon of Boccioni and Futurism at large, partly because of the high number of reproductions.

Over the following decades, eight posthumous editions of Unique Forms have been commissioned, a proliferation which would have been unlikely should the artist have survived (Boccioni argued against the use of bronze in his sculpture manifesto). The plasters of Unique Forms and Bottle were acquired by the Brazilian industrialist Francisco Matarazzo Sobrinho and today are in the Museum of Contemporary Art at the University of São Paulo. The bronzes, some from the plaster, others surmoulages, have had an even broader reach through worldwide exhibitions and museum displays. From MoMA to the Met, Tate Modern to the Kröller-Müller museum, the Hilti Art Foundation in Lichtenstein to the Hakone Open-Air Museum in Japan, Unique Forms has become a ubiquitous example of Boccioni’s search for dynamic form. The sculpture has been appropriated by contemporary artists, including Barry X Ball, Peter Coffin, and Francesco Vezzoli, and is even found on the Italian mint of the 20-cent euro coin. Unique Forms is a more apt testament to an artist whose dynamic life has been repeatedly recast in his absence for 100 years than any funeral eulogy.