At the water’s edge in front of St Mark’s Square, rows of sleek black gondolas rock forlornly in the waves, their blue covers untouched for months. A little way down the waterfront, the Squero di San Trovaso, a boatyard normally filled with the sounds of sawing wood and hammering nails, is uncharacteristically quiet. Requests for repairs and newly constructed boats have come to a halt. Even before the pandemic, the ancient craft of gondola-building was in decline, as its maestri retired and historic workshops closed their doors. A year of lockdowns and travel restrictions has only worsened the situation.

Traditional craft objects often use costly materials, are laborious to create and require expert knowledge – all reasons for the growing precarity of artisanal work. The hand-crafted gondolas of Venice exemplify these characteristics. At the Squero di San Trovaso, whose origins date back to around 1600, maestro Lorenzo Della Toffola makes just one gondola a year in order to reserve time for repairing the existing gondolas. As his daughter Francesca Della Toffola explains to me via email, the workshop is particularly passionate about preserving these gondolas, which can last up to 40 years with careful maintenance.

View of Squero di San Trovaso, photographed in 2014. Photo: Andreas Solaro/AFP via Getty Images

Making a gondola from scratch, Della Toffola says, takes around two to three months of daily work. It begins with obtaining the eight different types of wood, including elm, oak, mahogany and cherry, used for different parts of the boat. To build the gondola, Lorenzo Della Toffola and his two workshop collaborators use only ancient manual construction techniques, not even using machinery to lift the boats out of the water. Some 280 pieces of wood are nailed together, not glued (as Francesca Della Toffola emphasises), and ‘even the curvature of the wood is still done with water and fire’.

Although traditional techniques have changed little, the form of the gondola has undergone alternations over the centuries. Gondolas became asymmetric in the 19th century – allowing them to be rowed by a single gondolier instead of two – and later lost their felze, a small cabin that offered privacy but was abandoned as it hindered tourists’ views. One might expect to find highly detailed technical drawings on the workshop walls but, Della Toffola says, ‘the most incredible thing is that there are no projects or drawings written for the construction, it is all experience handed down for generations’.

This system of knowledge sharing is leaving the craft vulnerable. Squero di San Trovaso is one of a couple of boatyards or squeri in the city with a handful of maestri and apprentices who construct boats in a traditional manner. Another is Squero Tramontin, whose founding maestro Domenico Tramontin is credited with inventing the asymmetrical shape of the gondola still used now. Other boatyards in Venice, however, have begun to use non-traditional marine plywood instead of aged hardwoods. This is partly because of the scarcity of good quality hardwood, but also for the greater ease of construction and at the preference of gondoliers, as marine plywood requires less maintenance. The gondola’s accessories, traditionally constructed by hand, are now also often industrially produced.

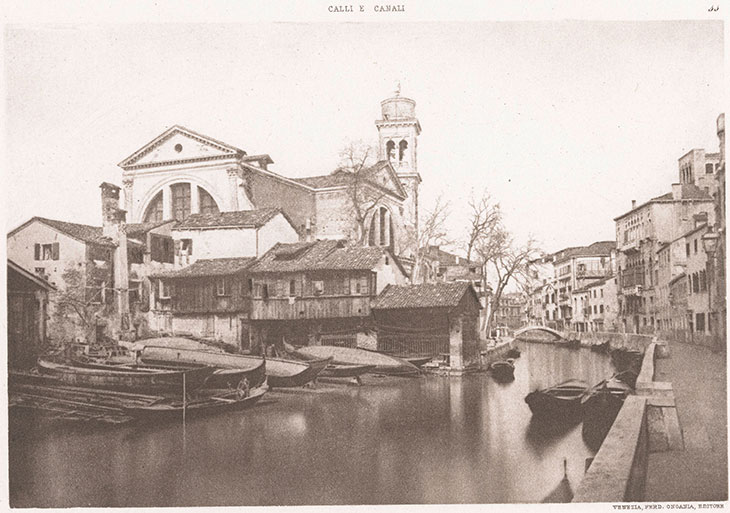

View of Squero di San Trovaso, photographed in c. 1888–98. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

The anthropologist Elisa Bellato has called this an ‘identity crisis’ for the artistic manufacture of the gondola. While the boat made with cheaper materials may be indistinguishable to the untrained eye, its authenticity – not to mention quality and craftsmanship – has been lost. Bellato suggests that this modern gondola is more of a simulacrum than a true specimen, emptied of the values and knowledge accumulated over centuries.

Now the pandemic is creating an even greater crisis. Saverio Pastor, president of the El Fèlze association of craft workers involved in all areas of gondola construction, including those who make oarlocks and metal ornamentation, tells me: ‘Covid has been a disaster because all the gondoliers have stopped work and so the whole chain of work has stopped.’

Photo: Marco Secchi/Getty Images

Della Toffola fears an unchecked decline: ‘The maestri are now very few and can be counted on the fingers of one hand […] and it is very sad that no one worries about it.’ But for the Della Toffolas, persevering with traditional construction techniques is fundamental. This is because hand-manufacturing a gondola is the only way to ensure the unique form of each one. ‘It is impossible for gondolas to be identical,’ says Francesca Della Toffola. ‘They are customised for those who commission them.’

This customisation includes the characteristic asymmetric curve of the bow and stern of the boat, created using the technique of wetting the wood then heating it with fire. The maestro uses this method to bend the wood to the exact degree requested by the gondolier, to ensure that the boat’s form is well balanced and aesthetically appealing. Accessories including the wooden oarlock, brass prancing horses, and ferro di prua (the distinctive metal S-shaped decoration at the bow) are also custom-made in other artisans’ workshops throughout the city.

The closure of these workshops would mean the loss of an important part of Venice’s cultural heritage, one which is celebrated in the city’s Naval History Museum. The museum houses Peggy Guggenheim’s personal gondola, which is equipped with a felze cabin, and is displayed alongside other historic examples. ‘We are not overly nostalgic – we know that many gondoliers prefer marine plywood, and even builders too – but it means throwing away 2,000 years of culture and knowledge,’ says Pastor. ‘Can a city like Venice, with such an important history of constructing boats in hardwood planks, permit itself to pass without a problem to having only boats in marine plywood or even plastic?’

The Della Toffolas believe that saving these ancient crafts might also contribute to the ‘saving’ of Venice itself. The canal city has for decades been losing residents at an alarming pace, caused in particular by the unsustainable levels of tourism pre-pandemic. Venice, it could be argued, is becoming a simulacrum itself. But squeri are, as Bellato observes, ‘anthropological’ places, ‘where belonging and conviviality are cultivated and lived’. When tourists do return, hopefully at levels that aid rather than alienate the resident population, supporting artisanal activities like those of the gondola workshops will be an important step in keeping Venice as a living city.

For now, at Squero di San Trovaso, hammers and nails languish on workbenches. But there is a glimmer of optimism thanks to the younger generation of Della Toffolas. ‘We hope to be able to continue for a while,’ says Francesca Della Toffola. ‘Fortunately my father has been teaching the trade to my 24-year-old brother for a few years.’ She, in turn, manages the administrative side of the business.