From the May 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Glyn Philpot (1884–1937) was one of the most famous and highly paid portraitists of his age, widely regarded as the rightful heir to John Singer Sargent. When, in the early 1930s, he appeared to abandon his hitherto opulent and bravura method of painting for a pared-down modernism, some of his admirers were both surprised and dismayed; but he had in fact been an idiosyncratic and unpredictable artist from the outset. Alongside his paintings he made many fine sculptures that show the marked influence of Michelangelo and Rodin. He did some very stylish paintings of plants in the 1930s that were exhibited in the interior designer Syrie Maugham’s shop in Mayfair and created murals for Philip Sassoon at Port Lympne in Kent and Lord and Lady Melchett at Mulberry House in London. He was homosexual and a devout Roman Catholic convert who painted scenes from classical mythology and the Bible that are both unsettling and wholly original. In addition, his frequent choice of Black subjects to paint was very unusual for the period. He was at once inside society, commissioned to produce portraits and decorative schemes for its moneyed and glamorous members, and placed himself outside of it by creating works that celebrated Black lives and displayed a distinct queer sensibility.

Like his contemporary Ronald Firbank, who moved in some of the same circles and whose fiction similarly features society figures, saints, flowers, the theatre and Black and queer lives, Philpot has remained something of a cult. Although his paintings have begun to command high prices, ‘Glyn Philpot: Flesh and Spirit’ at Pallant House (14 May–23 October) is the first major exhibition of his work since the one at the National Portrait Gallery in 1984. It has been curated by Pallant House’s director, Simon Martin, who has also written the accompanying monograph. When, 20 years ago, Martin did his MA on Philpot, he looked specifically at two aspects of the artist’s work, queer subtexts and the representation of Black models, that now have considerable currency, and this makes a reappraisal seem timely. The vast majority of Philpot’s work remains in private hands, and Martin has managed to trace several paintings that were considered ‘lost’ at the time of the NPG exhibition, doing ‘a huge amount of family-tree research on the last-known owners and their descendants’. As a result, he says, the Pallant House show will include paintings that ‘haven’t been exhibited for a century’.

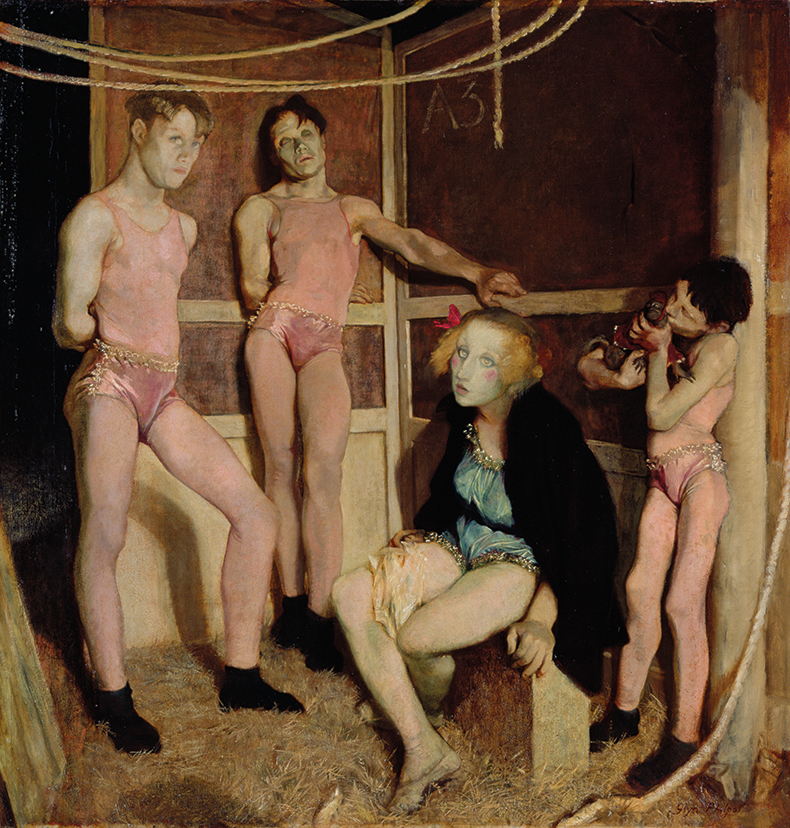

Manuelito, A Circus Boy (1909), Glyn Philpot. Courtesy Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam

Martin suggests that Manuelito, the Circus Boy marked Philpot’s ‘arrival on to the national and international stage’ when, in 1910, it was exhibited at both the Modern Society of Portrait Painters and the Venice Biennale. The painting certainly exemplifies what would become a notable aspect of Philpot’s work. The subject is richly caparisoned in a traje de luces costume, and takes up the traditional bullfighter’s pose, hand on hip, looking back over his shoulder towards the viewer. The background, however, is not an arena but a plain dark cloth casually draped over what appears to be a theatre flat, and the painting’s title tells us that this is not a real torero but merely a boy posing as one. Artifice and dressing up would become Philpot’s hallmarks as an artist, partly because he loved the theatre, opera and ballet. Throughout his career he painted performers in the roles he had seen them in on stage, including Nijinsky, Tamara Karsavina, Paul Robeson and Glen Byam Shaw. He was also fascinated by those anonymous players whose names would never appear in lights, such as the line of silvered chorus boys stepping on to the stage in Caprice: The Moon-Dance (1908), or the group of weary young performers taking a well-earned break in The Resting Acrobats (1924). A sense of theatre extends to paintings not directly related to the performing arts, and it seems possible that the many evenings Philpot spent in the stalls taught him how to make dramatic compositions on canvas. A Street Accident (1925), for example, seems less like a real event than something taking place on stage, with the players carefully blocked and lit and the narrow vertical slice of building behind them giving the impression of a painted backdrop. Similarly in Entrance to the Tagada (1931), the Black doorman who is letting customers into the fashionable Parisian nightclub is dressed like a ringmaster in a scarlet frock coat and white top hat and looks as if he is drawing aside the flap of a circus tent.

Theatrical gestures of concealment and revelation may well have had a particular resonance for a painter whose sexuality, while hinted at, could not be openly acknowledged. In 1918, Philpot was invited to do a painting for the Official War Artists scheme and proposed ‘A Bathing Parade’. This idea was vetoed, a committee member commenting: ‘I cannot say whether this is really a significant incident in the life of soldiers, but I will bet anything that Philpot suggested it because it gave him the opportunity of painting the nude.’ Philpot was instead sent off to produce portraits of admirals and of Dame Katharine Furse, head of the Voluntary Aid Detachment of wartime nurses. Rather more enjoyable, one imagines, were the circumstances surrounding two other portraits he did during the war. One was of a handsome Man in a Flying Jacket (1916), who remains unidentified but may have been a member of the Royal Flying Corps. The other was of the homosexual soldier-poet Siegfried Sassoon (1917), suggested as a subject by Robbie Ross, the friend and executor of Oscar Wilde and a central figure in queer circles of the period.

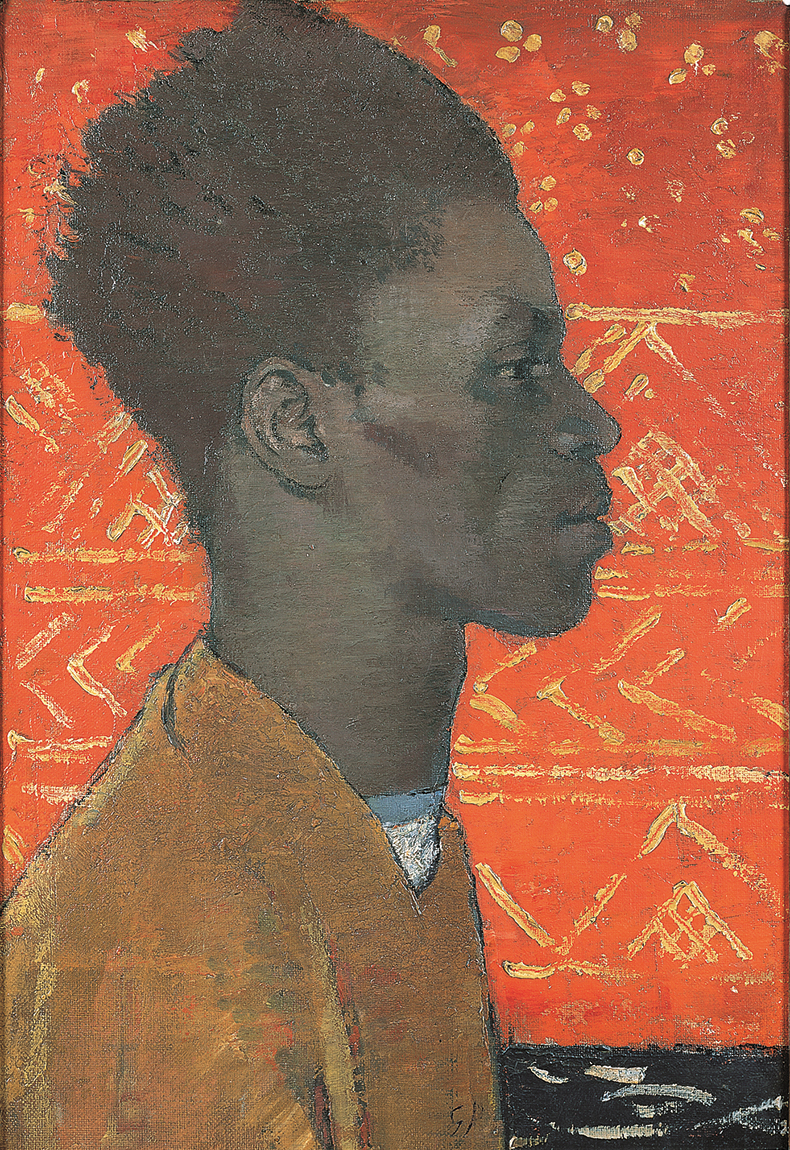

Portrait of Henry Thomas (c. 1934–35), Glyn Philpot. Pallant House Gallery, Chichester

After Philpot moved to Paris in the spring of 1931, he may well have been talking about both his professional and personal life when he told the artist Eliot Hodgkin, ‘The sense of freedom I get here is something I can’t find in London.’ Simon Martin observes that the studio Philpot took in a sleek modernist building on the Boulevard Raspail was very different from the stagy and antique-filled ones he occupied in England, and that the work he did in it reflected this. As Philpot explained, whereas he had formerly, in imitation of Old Masters, built up his pictures with underpainting and then ‘worked the colour with successive glazes’, he had now abandoned glazes altogether. The result was a lighter and far less rich palette, but another change was that even his classical figures now occupied contemporary spaces. In 101st Afternoon with Penelope, for example, Ulysses’ wife and son may be awaiting his return from the Trojan War, but they are doing so amid Bauhaus furniture.

Two brief trips to Berlin in 1931, during which he explored the city’s notorious nightlife, also had a profound influence on his art. ‘I believe I shall work better for having seen sides of human nature which I have never looked on before,’ he reported, and among those he met in Berlin was one of Christopher Isherwood’s lovers, Karl-Heinz Müller. Whether or not Müller’s relationship with Philpot was a sexual one, the paintings that resulted undoubtedly made more explicit the homoeroticism detectable in the artist’s earlier work. Müller, easily identifiable because of his Slavic cheekbones and a left hand from which the ends of two fingers are missing, was depicted in three of the paintings in Philpot’s exhibition of new work at the Leicester Galleries in June 1932. These were two portraits (one now lost) and the mysterious Fugue (1931–32), in which Müller appears in triplicate – nude, bare-chested, and fully clothed – apparently being assisted on life’s journey by the figure of Artemis. More startling still is the tightly framed image of Müller in St Sebastian (1932), haloed, naked and bound to a rail, his chest pierced by two slender arrows. The image is cropped just above the penis, but even so, and even by the standards of many paintings of the saint, the picture is so transparently queer that it was never exhibited during Philpot’s lifetime and after his death was discovered in his studio turned to face the wall.

The Resting Acrobats (1924), Glyn Philpot. Leeds Art Gallery, Leeds Museums and Galleries

Also from this period are Philpot’s two supremely elegant portraits of Julien Zaïre, a strikingly handsome Black cabaret artist in evening dress. These Jazz Age images are very different from the more traditional paintings Philpot did of Black subjects (probably professional models) before the First World War, and those of Henry Thomas, the Jamaican man Philpot painted and sculpted many times from 1928 onwards. It is the early and less well-known paintings that particularly interest Martin because British paintings of Black subjects from this period – Harold Gilman’s Portrait of a Black Gardener (c. 1905) apart – are rare. Historical portrayals of Black subjects by white artists have now become controversial, but while some of Philpot’s paintings had titles such as Head of a Negro, Martin argues that even these are clearly portraits of individuals rather than generic images of race. ‘I take the view that Philpot made an important contribution to the representation of Black people in 20th-century art in a largely sensitive way, and that’s a positive thing, providing a visual record.’ These pictures will undoubtedly attract a good deal of attention, but they will take their place among more than 100 other paintings, drawings and sculptures in an exhibition that promises to reveal the remarkable range of this hitherto neglected artist.

‘Glyn Philpot: Flesh and Spirit’ is at Pallant House, Chichester, from 14 May–23 October.

From the May 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.