‘China’s 8 Brokens: Puzzles of the Treasured Past’ at the MFA Boston (until 29 October) is a marvellous and bewildering exhibition. It is marvellous because the paintings are marvellous – stunningly realistic trompe l’oeils made between the late 19th and early 20th centuries with compositions consisting of the sort of items one might find scattered across a desk: scraps of paper, knick-knacks, old tickets or notes. The items are in poor shape – the bits of paper are burnt around the edges or torn, remnants of embroidered tapestry are threadbare. These trompe l’oeils really do fool the eye – even the faded ink from a stone seal is painted on, not rendered by an actual stamp.

Scepter (1950), Zheng Zuochen. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The exhibition is bewildering because the paintings are puzzles, rebuses of sorts, which, after having been deciphered, evoke sprawling historical narratives, but also because this style of painting fell out of fashion around the middle of the 20th century and was all but forgotten by the 1980s. This is the first museum exhibition to examine the genre closely, and it sets a high bar both in terms of research and the careful elucidation that accompanies these strange and wonderful works. The term for these paintings in China is bapo, which translates into ‘eight brokens’; the word ‘broken’ refers to the state of decay of the objects being depicted, while ‘eight’ is considered a lucky number. That the objects are the worse for wear is also a blessing: imperfections, as in many other cultures, are valued for not invoking the envy of the gods and thus inviting misfortune.

Understanding the value of these works requires some assistance (which the MFA diligently provides via wall texts). Each painting is a homage to Chinese culture, particularly the art of calligraphy. The importance of calligraphy as an art form in China can’t be overstated – the emphatic brushstroke, valued for its gestural flair and beauty, is revered. The works of famous calligraphers were chiselled into stone to preserve the mastery, and so that devotees could create rubbings of their own to study. Thus the scraps of paper that make up the bulk of the compositions usually refer to famous works of calligraphy. Sophisticated viewers would recognise, for example, a 9th-century poem transcribed by an 18th-century calligrapher. In a helpful attempt to ‘unpack’ the contents of the paintings, the museum displays some of the objects to which the paintings refer, including a roof tile that is approximately a thousand years old. There are four Chinese characters impressed in the clay, making it an invaluable object to calligraphy enthusiasts who craved knowledge of the form’s history and provenance.

Lotus Summer of the Xinghai Year (1911), Liu Lingheng. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

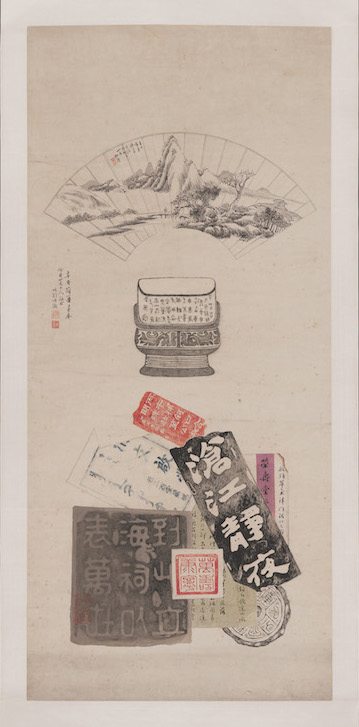

Viewers without extensive knowledge of Chinese history will find the bapo paintings abstruse. Certainly the layers of references are extensive. The painting Lotus Summer of the Xinghai Year (1911), by Liu Lingheng, contains, aside from the usual scraps of paper, a rubbing of a bronze and an open fan on which is painted a landscape in imitation of an 18th-century painting. Copying other works of art was common practice in China, and to see copies of copies only cements the sense of respect for history and culture passed down over generations.

The paintings are often subtly witty. The scraps of paper in A Complete Picture of 100 Years, made by Zhu Wei at some point during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, resolve into the shape of a dragon. In other works, deference to the ancient and the Chinese is tempered by hints of modernity and enthusiasm for increasing exposure to foreign cultures brought in by trade: a painting of a fan from 1942 by Yang Weiquan features a label for British toothpaste. English, albeit garbled, appears in another work from 1927 by Yuan Runhe: the word ‘boatguh’ (maybe a play on ‘boat go’ and maritime travel) is stamped on to an envelope.

But the paintings are also deeply mournful. The 19th century in China was turbulent, with one violent conflict giving way to the next as the country was ravaged by domestic rebellions, as well as British and French invasions. The turmoil paved the way for the toppling of the imperial dynasty in 1911 and the invasion of the Japanese in the 1930s, as well as the Second World War. One four-part work, Burned, Ruined, Damaged Fragments (1938) by Li Chengren contains an inscription referring to the first emperor of China, Qin Shi Huang, who not only commissioned the thousands of terracotta warriors to guard his tomb but also destroyed nearly all of the Confucian texts because he was afraid they would inspire insurrection. In a typically quiet, gently allusive puzzle at which these paintings excel, the mention of this historical tragedy may be a roundabout way of paying tribute to the Massacre of Nanjing during the Sino-Japanese war, in which almost 300,000 people died.

Burned, Ruined, Damaged Fragments (one of four) (1938), Li Chengren. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

It is ironic that a genre obsessed with history and its preservation should have been swept aside. (Many of the paintings are credited to ‘unknown’; the artists’ names lost to time.) One explanation for the bapo paintings’ diminished reputation is that scholars and enthusiasts of Chinese art prized abstraction above realism, and these paintings are painstakingly realistic. The paintings were made to be sold, and their explicit commercialism did not lend them to long-term appreciation. Indeed, one can see how a critic could write off the bapo works as academic. But they are not gimmicky. Subtle and exquisitely made, bapo paintings are more than worthy of a place in the canon. Perhaps most importantly they add a new dimension to the phenomenally rich history of Chinese art – and hint at further depths as yet unplumbed.

From the September 2017 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here