Leering businessmen, military officers with empty skulls, and ranting demagogues: George Grosz is known for his savage depictions of the Weimar Republic’s ruling classes. It was on account of such works that he emigrated to the United States when Hitler seized power. In exile, he turned reactionary himself, publishing an autobiography in 1946, in which he rejected his former political engagements (he had once produced graphics for the Communist party; now he said they were the same as the fascists) and painting sentimental landscapes and erotic vignettes from his home in Long Island.

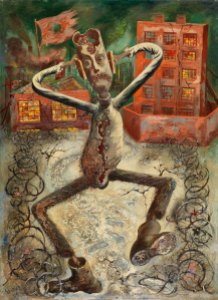

The Grey Man Dances (1949), George Grosz. George Grosz Estate. © Estate of George Grosz, Princeton, NJ/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2023

This is how the story has usually been told, but a new exhibition puts paid to the idea that his later career was apolitical. Das kleine Grosz Museum, a tiny institution dedicated to the artist, which opened in a former petrol station in Berlin in 2022, has assembled a selection of Grosz’s works from the years immediately after the war. The Stick Men drawings and paintings – the title is Grosz’s own – show wasted figures in blasted landscapes. Ragged and damaged, with massive eyes they stare forlornly out at the viewer.

Although his critique is not as direct in these works as in those of the 1920s, Grosz is unmistakably casting a vitriolic gaze on the world after the Second World War. These shackled, skeletal bodies inevitably suggest survivors of the concentration camps, a suspicion confirmed by the fences that surround the figures. No wonder the paintings found no audience in Germany, where the battered populace ‘saw themselves as the victims, and thus had the dubious good fortune of not having to think about the real ones’, as Harald Jähner puts it in his account of the period, Aftermath: Life in the Fallout of the Third Reich (2019).

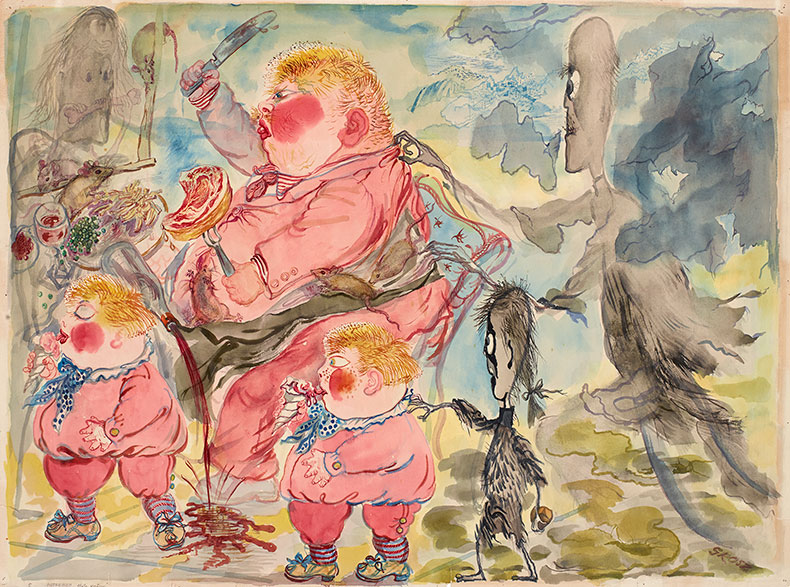

But there is an ambiguity at work here. After the defeat, the former supporters of the Nazis also starved. Grosz was in frequent correspondence with friends who sent letters complaining about the conditions in Germany. He incorporated these reports into paintings such as the watercolour Disturbed While Eating (1947). Here, the emaciated figures are spectres at the feast of a rotund family guzzling chops and ice creams, in what seems to be an unflattering portrait of American affluence. Not all these figures, however, are entirely sympathetic. In The Enemy of the Rainbow (1946), a stick man tears a rainbow flag – the only colourful object in a grey, barbed-wire-strewn landscape – to shreds.

The Enemy of the Rainbow (1946), George Grosz. Sammlung Judin, Berlin. © Estate of George Grosz, Princeton, NJ/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2023

What is to be made of this if the initial identification of the stick men with concentration camp inmates is maintained? We would see in these figures a double image of the oppressed and the oppressor: the former oppressor turned victim, the victim as perpetrator. It is a complicated and discomforting image, ‘in part tragic, in part grotesque’, as the artist put it in a letter of 1946.

Grosz does not spare himself from criticism. Between 1947 and 1950 he produced a series of three self-portraits presenting himself as a stick man. The third of these, a large oil painting titled The Painter of the Hole II (1948–50), is included in the show. It is an arrestingly weird image: the artist is surrounded and almost hidden by canvases, one of which he presents to the viewer while glaring out at us with a paintbrush gripped in his downturned mouth. The colours are lurid, kitsch even, as are the two incongruously cute mice which perch on the paintings. The latter are all penetrated by massive holes (incidentally, these images precede Lucio Fontana’s slit canvases by one year). The hole cut into the central canvas, which should reveal the body of the artist, instead shows a patch of blue sky. His head is penetrated by an identically shaped aperture.

The Painter of the Hole II (1948–50), George Grosz. Sammlung Judin, Berlin. © George Grosz, Princeton, NJ/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2023

The curators argue that, as well as commenting on the legacy of the war, these paintings are a salvo against the increasing dominance of abstract painting of the post-war years. Grosz was certainly not discreet about his disapproval of the Abstract Expressionists, especially the work of Pollock (he had been criticising abstraction since the mid 1920s). In The Grey Man Dances (1949) the figure seems not to be dancing so much as stamping on the snowy ground, which, as the curators point out, looks a lot like the then-fashionable action painting. His lips are sewn shut, his skull is smashed and he has boards nailed to his ears. This could well be a protest against the non-figurative painting being celebrated in his adopted home at the time.

But while this interpretation is convincing enough, it’s hard to see these works as straightforward celebrations of figuration. The artist in The Painter of Hole is brainless and his works are vacant, mere holes. Furthermore, they employ a sickly colour palette borrowed from mass culture. In other words, they are a continuation of Grosz’s Dadaist anti-art, for all their finely honed technique. As such they are akin to the post-war kitsch of avant-gardists such as Magritte, Dix and Picabia. Long seen as deplorable lapses in quality, these artworks should instead be understood as bitter attacks on the failure of the supposedly progressive aesthetics the artists had once espoused. Far from being apolitical or disengaged, these are Grosz’s very angriest paintings.

Disturbed While Eating (1947), George Grosz. Sammlung Judin, Berlin. © Estate of George Grosz, Princeton, NJ/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2023

‘George Grosz: The Stick Men’ is at Das kleine Grosz Museum, Berlin until 30 October. It will be at the Hecksecker Museum of Art, Long Island, from 11 May–1 September 2024.