With hundreds of exhibitions and events vying for your attention in London during Frieze week, Apollo’s editors pick out the shows they don’t want to miss

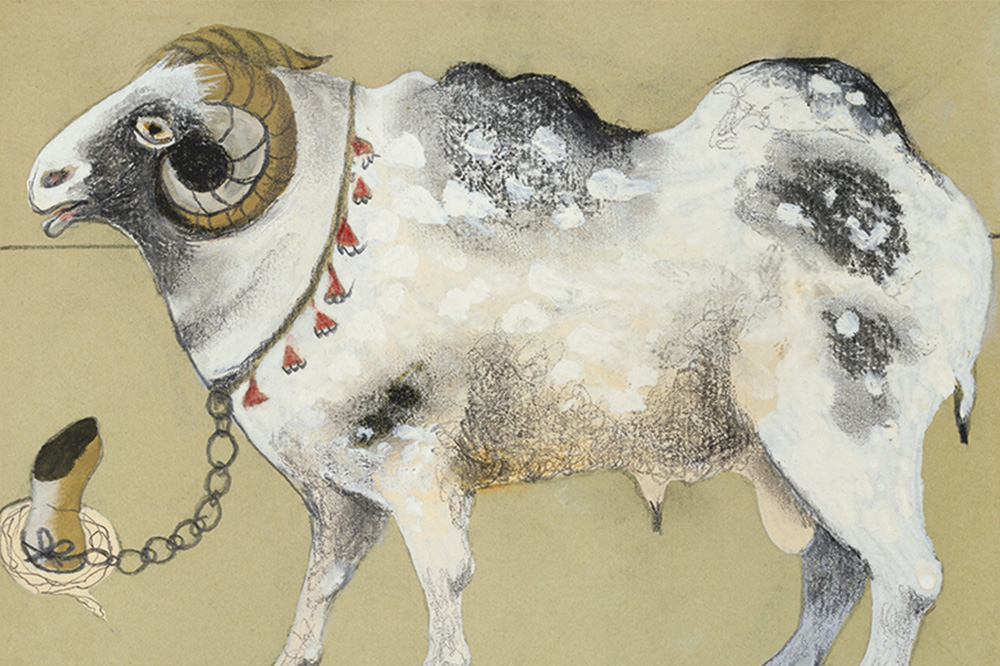

Romuald Hazoumè is best known for his masques bidons – masks composed principally of discarded petrol cans, which the Beninois artist has been making since the 1980s, putting him at the very forefront of a trend for constructing work from recycled materials that has since proliferated across Africa. A sardonic reimagining of African masquerade traditions, they are intended both as a pointed gesture towards the West – ‘I send back to the West that which belongs to them, that is to say, the refuse of consumer society that invades us every day,’ he has said – and a means of cocking a snook at African politicians. This show of new work at October Gallery, ‘Carnaval’, widens the lens to include global figures whose ‘masks’ – in the form of offshore shell companies – were stripped off by the revelations of the Panama and Pandora Papers. ‘Some of them might even be people you may well recognise!’, Hazoumè says – and though the titles are teasingly cryptic, I have my suspicions that Blaireau (French for ‘badger’) may depict a certain former British prime minister.

Blaireau (2022), Romuald Hazoumè. Courtesy the artist and October Gallery, London; © Romuald Hazoumè

If you find yourself unsated as you leave William Kentridge’s extensive retrospective at the Royal Academy, then it’s a hop, skip and a jump to Cork Street, where Goodman Gallery is presenting something of an addendum in the form of a terrific new film by the South African artist. Oh to Believe in Another World continues Kentridge’s reflection on totalitarian regimes of the 20th century. Its jumping-off point is the dismissal by Stalin in 1934 of Shostakovich’s Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk as a ‘deliberately dissonant, muddled stream of sounds’ – criticism that Kentridge attempts to reclaim as a virtue. The film splices bits and pieces of the composer’s Symphony no. 10 and other works into a kind of aural collage, which becomes the soundtrack for a series of protagonists – among them Stalin, Lenin, Trotsky, Mayakovsky, Elmira Nazirova and Shostakovich himself, their heads cartoonishly collaged over footage of dancers – to act out the frustrations, hopes and disillusionments of the Soviet era amid an abandoned Soviet museum. The intricate cardboard set, which Kentridge made and filmed with a miniature camera, is on display upstairs.

Black Dog (2021), Anne Rothenstein. Photo: Todd-White Art Photography; courtesy the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery, London; © Anne Rothenstein

Anne Rothenstein’s bold command of pictorial space, in her enigmatic interiors, portraits and landscapes, is reminiscent of no-one so much as Pierre Bonnard – though her palette, which generally takes on nocturnal or sunset scenes, is colder and more muted, bringing Munch to mind. Rothenstein’s work is familiar to many from the cover of the London Review of Books, which has featured her designs since 2012; this show at Stephen Friedman offers a chance to see her recent, taut paintings.