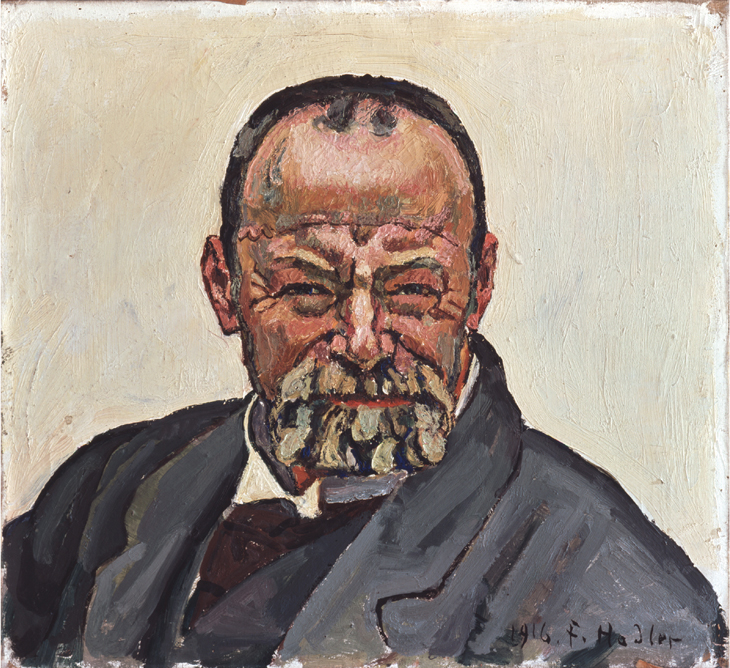

Visiting the Musée d’art et d’histoire in Geneva, you soon get used to this face: bearded, with an intense stare from beneath a furrowed brow, and a defiance that seems to ask ‘who do you think you are?’ It is the Swiss artist, Ferdinand Hodler (1853–1918), one of the hundred or so self-portraits he painted, and his fierce scrutiny is aimed at himself, not us.

Self-portrait (1916), Ferdinand Hodler. Photo: Y. Siza; © MAH Genève

Hodler was born in Bern, but made Geneva his home, and it is here that a varied programme of centenary exhibitions and events is being staged this year across the group of institutions that make up the Musées d’art et d’histoire de Genève. The centrepiece is a major monographic exhibition entitled ‘Hodler//Parallélisme’ at the Musée Rath (20 April–19 August). A collaboration with the Kunstmuseum in Bern (where the exhibition will be shown from 14 September–13 January 2019), it unites around 80 Hodler paintings drawn from public and private collections. It takes as its theme the concept of ‘parallelism’, a term Hodler coined to describe the unifying philosophy of his approach to art. It refers to the processes of simplification, symmetry, and the repetition of motifs by which he sought to isolate and extract the essential qualities of nature. He perceived there to be a fundamental order in the universe, which it was the role of the artist to reveal.

Lake Geneva with symmetrical reflections (1905), Ferdinand Hodler. © MAH Genève

Heralding the exhibition, in March the Musée d’art et d’histoire (MAH) unveiled the first stage of a comprehensive rehang of its permanent collection, including a major temporary display of Hodler’s work to accompany the programme. As Lada Umstaetter, chief curator of fine arts at the MAH, tells me, the Hodler programme and the redesigned galleries offer an opportunity to look afresh at the collection.

‘The public is familiar with the landscapes of Hodler and visitors will be able to find these iconic works,’ she explains, ‘but we also wish to show aspects of his work and life that are less known. “Hodler Intime” [“Hodler, an intimate portrait”; opened 1 March] presents his private world, especially through his portraits and self-portraits.’ Occupying the largest of the redesigned spaces, this display seeks to get behind the mask of the ‘ultimate Swiss artist’. Annotated with quotations from his personal notes and correspondence, it explores who he was through his relationships with the women in his life, his friends, and patrons. Hodler’s isolated tree portraits, such as Spring Landscape with Flowering Trees (c. 1895), are some of the most sensitive and beautiful of his works, and can be regarded as visual metaphors of the artist himself: standing alone, yet rooted in their particular place in the world. ‘Man himself is symbolised by the tree,’ Hodler said, ‘it is the symbol of life as a whole. It represents individual and universal life. Life below and life above.’

Spring Landscape with Flowering Trees (c. 1895), Ferdinand Hodler. Photo: B. Jacot-Descombe;

In the centre of the ‘Hodler Intime’ gallery the curators have placed a set of Secession-style furniture that belonged to the artist and furnished his Geneva apartment. The suite was designed by Josef Hoffmann (1870–1956), one of the founders in 1897 of the Vienna Secession, of which Hodler would later became a member. A principle espoused by the Secession was there should be no distinction between fine and decorative arts. Umstaetter, who joined the museum in 2017, tells me one of her aims is to break down the traditional separation between the museum’s departments, by introducing more works from other parts of the collection, such as furniture, musical instruments, antique sculpture or enamel portrait miniatures, into the fine art galleries. By doing this, she maintains, we will gain a fuller understanding of the cultural context in which the paintings belong.

Another important figure associated with Hodler, but little known today, is his teacher, the Genevan painter Barthélemy Menn (1815–93). The Cabinet d’arts graphiques is showing an exhibition of drawings, watercolours and studies by Menn (until 8 July), which will reveal, among other things, the fundamentals of composition and design that he imparted to Hodler and his other pupils. Menn discovered the young and impoverished Hodler copying landscapes by Alexandre Calame in the Musée Rath. Hodler would later say ‘I owe everything to Menn’.

Later in the year, the applied arts galleries in the MAH will present a cross-disciplinary display, ‘Hodler and the Swiss Mercenary: from Myth to Reality’ (28 September–30 December), bringing together pieces from its important collection of arms and armour with three Hodler paintings: Halberdier (1895/96), The Flag Bearer Hans Baer Wounded at the Battle of Marignano (1898–99) and The Battle of Morat (1917). Having achieved a degree of recognition in the early 1890s, Hodler was commissioned to paint a number of large-scale public works on patriotic themes, notably panels for the Swiss National Exhibition in 1896, and for the gallery of arms and armour at the Swiss National Museum in Zurich in 1898. The display in the applied arts gallery will explore Hodler’s depictions of martial heroism in relation to ideas of Swiss national identity that developed in the 19th century.

Halberdier (1895/96), Ferdinand Hodler. Photo: F. Bevilacqua; © MAH Genève

Hodler’s influence on Genevan painters will be the subject of an exhibition at Maison Tavel, which will bring together around 30 works by subsequent generations of artists in the city (28 September–24 February 2019). Finally, to understand how Hodler’s critical reputation evolved during his lifetime and subsequently, the Art and Archaeology Library will show a display of press articles, books and art catalogues from its collections (5 November–26 May 2019).

As the varied nature and location of these events would suggest, the Musée d’art et d’histoire is considerably more than an art museum. Its collection, which also encompasses antiquities, archaeological objects, decorative art, and much else, is older than the institution, and dates back to the Reformation. It has its origins in the Geneva Academy, established by John Calvin in 1559, the library of which developed as a cabinet of curiosities. Further collections were formed in artistic institutions established during the Enlightenment, such as the École de dessin, set up in 1751, and the Société des arts, founded in 1776. Geneva gained its first museum in 1820, with the creation of the Musée académique, housing natural history, archaeology, and ethnographic collections. This was joined by a purpose-built art museum in 1826, the first public institution of its kind in Switzerland. Financed by two sisters – Jeanne-Françoise and Henriette Rath – it still carries their name, and is now used exclusively for temporary exhibitions, hosting two or three a year.

Two substantial collections, effectively private museums, were given to the city in the second half of the 19th century. The first, in 1871, consisted of pieces Walther Fol had acquired in Italy: Etruscan and Roman artefacts, Renaissance paintings, and 16th- and 17th-century objets d’art. The second, bequeathed by Gustave Revilliod in 1890, comprised a neo-baroque mansion (now the Musée Ariana) with surrounding parkland, and the historical and art collections it contained.

By this point, Geneva had accumulated a hotchpotch of diverse collections dispersed through numerous buildings, not all of which were ideal homes for their contents. Uncomfortable with this disorderliness, the city’s cultural leaders developed a scheme to consolidate everything under one roof in an encyclopaedic museum. The Swiss National Exhibition, held in Geneva in 1896, gave further impetus to these plans. As has been the case through much of the collection’s development, the project was the initiative of private citizens, and most of the funding for the new museum came from one individual, Charles Galland, president of the Geneva stock exchange.

The museum opened its doors in 1910. Designed by a local architect, Marc Camoletti (1857–1940), it is an imposing neoclassical edifice in the Beaux-Arts style, modelled on the monumental exhibition buildings, the Petit Palais and the Grand Palais, that had been built for the Exposition Universelle of 1900 in Paris. When it opened it was one of the largest museums in Switzerland, with more than 7,000m2 of gallery space.

However, it soon became apparent that the building wasn’t big enough, particularly to house the reserve collection and support functions. The original centralising concept proved short-lived, and over time parts of the col- lection have been redistributed to subsidiary and specialist institutions, albeit in a more systematic way than previously. The Cabinet d’arts graphiques, with its extensive collection of works on paper, and the Library of Art and Archaeology were moved to a neighbouring building in 1952. Since 1986, Maison Tavel, a 14th-century townhouse and the oldest secular building in Geneva, has displayed items from the cultural and social history collection. Despite the dispersal of some of its holdings, the Musée d’art et d’histoire, with its four satellite museums and library, is the largest museum in Switzerland with around one million objects.

Umstaetter tells me that behind the scenes the museum is currently engaged in two major projects. The first will see most of the reserve collection moved from the main site to a new storage facility. The second will involve a more fundamental redefinition of the museum, involving much-needed renovation and extension of the building, for which an architectural competition will be launched during the next two years.

The collection displays are currently arranged over three floors. The ground floor is devoted to the applied arts and contains the collections of arms and armour originally from the city arsenal, furniture, musical instruments, metalwork, tapestries and textiles, as well as an internationally important collection of Byzantine art and objects. The lower-ground floor is home to the collection of Greek, Etruscan, Roman and Egyptian antiquities, which with 34,000 objects is the largest of its kind in Switzerland.

The Miraculous Draught of Fishes (1444), Konrad Witz. © MAH Genève

The fine arts collection occupies the entire top floor of the building. Our tour starts in the late Middle Ages, with the museum’s best-known piece, The Miraculous Draught of Fishes (1444) by Konrad Witz. Originally the external face of a wing of an altarpiece in Geneva Cathedral, it is a rare survivor of Reformation iconoclasm. Witz located the biblical scene in a lake landscape that is recognisably Genevan, with the snow-capped Alps and Mont Blanc on the horizon, which gives the painting the distinction of being the first topographically accurate representation in European art. Umstaetter explains that the panel provides an important point of departure for what follows, because it introduces the two strengths of the collection: landscape painting and portraiture, the latter through the donor portraits that appear elsewhere on the altarpiece.

The rehang will be carried out in two phases. The first has just been unveiled, and covers the modern period, dubbed ‘Corot to Christo’. The second, addressing the earlier periods – ‘Witz to Calame’ – is due to be completed by spring 2019. The last major redesign of the displays was about 15 years ago, Umstaetter tells me, and since then several incremental changes have disrupted the overall coherence of the presentation. The plan now is to return to a clearer chronological progression through the main galleries, with changing thematic displays in the side rooms.

Talking about her ambitions as chief curator of fine arts, Umstaetter says she aims to ‘bring back the fine arts collection to prominence and make it the backbone of the museum’. Displays that appeal to new visitors, as well as regular changes that keep local audiences coming back, are the key to achieving this. ‘It is very important for me to surprise the visitor,’ she continues, ‘to provoke strong visual reactions that will catch the interest of the first-time visitor […] but also to bring new insights or something unexpected to the confirmed art lover.’ Discussing the strengths of the collection, she says: ‘it has a foot in the local, with a strong body of Swiss art, and another in European culture as a whole, from the Middle Ages to the 20th century.’

The museum holds an exceptional collection of 18th- century pastels, with examples by Rosalba Carriera, Maurice Quentin de La Tour, and a substantial portion of the oeuvre of the 18th-century Genevan artist Jean- Étienne Liotard. Liotard was a widely travelled portraitist, who counted members of the papal court and the royal families of England and Austria among his clientele. In many ways his career typifies Swiss artistic cosmopolitan- ism, finding fame and fortune abroad, yet maintaining an idiosyncratic individualism that set him apart from the artistic circles in which he moved. By the mid 19th century Swiss artists were increasingly turning to their native landscape for inspiration, in search of mountain subjects that might appeal to a burgeoning sense of national identity. The museum has a fine array of works by the Swiss Romantics, including Alexandre Calame, François Diday and Pierre-Louis de La Rive.

Crossing into the redesigned modern section, the transition is obvious. The transformation is not simply down to the re-presentation of the art; the quality of the collection is markedly different here, with many more works by major, internationally renowned artists. The first room, for example, contains landscapes by Corot, Van Gogh, Cézanne and Pissarro, among others. Works by Swiss artists such as Giovanni Giacometti, Cuno Amiet, Alexandre Perrier and Alice Bailly are integrated into these displays, to show how home-grown artists responded and contributed to artistic movements from Impressionism onwards. The international contexts of Swiss art remained important; the role of the École de Paris in the early decades of the 20th century, for instance, is underlined with a display including works by Soutine, Modigliani and Chagall.

The Symbolist paintings that follow are much less sympathetic to the modern eye. Often characterised by arcane mysticism, overwrought emotions, and excessive nudity, they challenged the boundaries of taste in their own day. Their prominence in the display is an example of the way Umstaetter aims to confront the visitor with some- thing unexpected and visually striking. Carlos Schwabe’s The Wave (1907) is a good example: a seething tsunami of semi-clad women, their faces contorted in anguished howls as they point accusatorily at the viewer.

Félix Vallotton is an underappreciated Swiss artist, but one who is well represented in the collection. He had a strong sense of design, and is best known for his woodcuts, but he also created beautifully refined landscapes such as Sous-bois (1915) and Orange Groves at Cagnes (1923–24). He also turned out numerous monumental female nudes, which have an unsettling synthetic quality. The curators have chosen to display a number of these, including The Turkish Bath (1907) and The Slaying of Orpheus (1914). Challenging works, they would have been easy to leave out, but a full appreciation of Swiss art is not possible without contending with some of these eccentricities.

The Slaying of Orpheus (1914), Félix Vallotton. © MAH Genève

It was with his Symbolist paintings that Ferdinand Hodler eventually won the critical recognition he craved. He exhibited La Nuit (1889–90) in 1891 at the Musée Rath, but it scandalised Genevan society, who regarded the naked, entwined figures as obscene. However, it was more favourably received when shown in Paris a few months later. Exhibited alongside Le Jour (1899–1900) and L’Eurythmie (1894–95) at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1900 it was awarded a gold medal. But it was not until 1904, and with Hodler’s turn as guest of honour at the 19th exhibition of the Vienna Secession, that his work found international acclaim. Arguably, he was better appreciated in the German-speaking art world than the French. But the outbreak of the First World War and his public criticism of German war conduct resulted in him being ostracised from these circles. His art nevertheless had some influence on the development of German Expressionism. Oskar Kokoschka and Egon Schiele acknowledged him, for example, and Wassily Kandinsky praised his ‘melodic composition’.

After 1904, Hodler returned once again to landscape, to reflections on Lake Geneva and Lake Thun and the hazy luminosity of light in the Alps. It is in these late works that ‘parallelism’ is best expressed: his colours became more intense and he simplified the forms of the landscape, stripping away all unnecessary detail in search of harmony and clarity.

Lake Geneva from Chexbres (c. 1905), Ferdinand Hodler. © MAH Genève

Returning to the self-portrait, have I got to know Hodler any better? Certainly I come away with a clearer idea of who he was, the contexts in which he lived, and a fuller sense of his body of work. The museum’s stated aim is to ‘go beyond the patriotic image to which he is too often limited’, by offering many different approaches and angles that will appeal to the diverse audiences, local and international, that the institution serves. A similar philosophy informs the rehang, along with a conviction that the fine arts collection has much to delight new visitors – while offering unexpected surprises to those who already know it well.

‘Hodler/Parallelism’ is at the Musée Rath, Geneva, until 19 August.

From the April issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.