From the December 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

It was January 1911 and the petrol king of Stockholm was giving a party. Emanuel Nobel – Alfred’s nephew – liked to mark an occasion, and it may have been the weather that inspired the idea of giving each of the ladies present an icicle. He called on the Russian jewellery house of Fabergé, where he was an established customer. Before long, he received a set of snowflake-shaped brooches in rock-crystal, touched with a frost of tiny diamonds, to stuff into his guests’ napkins. These snowflakes, evoking the harsh winter of Fabergé’s homeland, soon became one of the firm’s most popular designs (the financier J.P. Morgan bought a few for his daughters). Their creator, the 23-year-old Alma Theresia Pihl, apparently still had them on her mind when she turned to her next project – Fabergé’s most prestigious annual commission – the Imperial Easter Egg for 1913.

Pihl’s ‘Winter Egg’ can currently be seen in the exhibition ‘Fabergé in London’ at the Victoria and Albert Museum (20 November–8 May 2022). It appears frozen in rock crystal, with icicles engraved on the interior of its semi-transparent body, and its exterior studded, like Emanuel Nobel’s brooches, with a rose-diamond frost. Dimly visible through the surface, as if through a cold mist, is the egg’s ‘surprise’, a platinum basket of wood anemones, each flower carved from a single piece of white quartz, with jade leaves set on gold wire stems that emerge from a bed of gold moss. Flowers were themselves a prized commodity at the Russian court, where the promise of spring was often fulfilled by roses preserved on ice blocks and transported by train from the south of France. Fabergé’s quartz bouquet promised a more enduring bloom, but the egg itself was so friable that it could be worked by only the firm’s most experienced hands. Appropriately, it could not tolerate the slightest heat: as a result, its settings were never soldered.

Winter Egg, with a basket of anemones (1912–13), designed by Alma Theresia Pihl and made by Albert Holmström for Fabergé. Private collection

The Winter Egg was presented to Nicholas II by Peter Carl Fabergé (1846–1920) himself on Good Friday, and by Nicholas to his mother, the Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna, on Easter Sunday 1913. Nicholas was continuing a tradition originally established by his father, Alexander III, in 1885, the year Fabergé became the Romanovs’ official court jeweller. By the turn of the century, this Russian-born goldsmith of French Huguenot extraction, who had taken over his father’s small business in 1872, had transformed ‘Fabergé’ into a multi-national enterprise, spread across several specialist workshops, each headed by an expert workmaster. The firm employed around 500 people making everything entirely by hand. The Imperial Easter egg dominated the annual work-cycle, development of the new design beginning as soon as the previous one had been delivered. The process of their creation was cloaked in secrecy, and Peter Carl Fabergé – a kind of anti-Bartleby the Scrivener – would respond to any nosiness with the gnomic phrase ‘Your Majesty will be satisfied.’

Kamer Kazak (chamber cossack; Nikolai Pustynnikov; 1912), Henrik Wigström for Fabergé. Private collection. Image courtesy Wartski, London; photo © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

Fabergé, wrote Vita Sackville-West in the late 1930s, ‘worked his small conceits in a manner suited only to the offensively rich people able to buy them’, and the firm’s work in general, and the Imperial Eggs in particular, have indeed become a shorthand for the doomed decadence of the monarchs, aristocrats and oligarchs who formed its most devoted client base, on the eve of the First World War. Nicholas II’s commission for a series of miniature hardstone Fabergé figures representing various Russian ‘types’ suggests this perennially embattled emperor found the jeweller’s miniature world appealingly manageable. He even had Nikolai Pustynnikov and Andrei Kudinov, his mother’s Cossack bodyguards, rendered in gemstones, with dark green nephrite coats and black onyx boots, their beards of grey jasper and sapphires for eyes. In the same year Nicholas’s mother received the Winter Egg, the Easter gift for his wife, Alexandra, celebrated the tercentenary of the Romanov dynasty: the gold surface of this egg is adorned with ivory miniatures of all 18 Romanov rulers, framed with rose-cut diamonds. In retrospect, this celebration of imperial endurance feels pre-emptive. Nicholas II’s final Fabergé bill, issued on 25 April 1917, was addressed to ‘Mr Romanov, Nikolai Aleksandrovich’. The corresponding egg never reached him.

At 24,700 roubles, the Winter Egg was the most expensive Fabergé egg ever made. Yet despite the apparent opulence of his creations, virtually all of Fabergé’s ‘small conceits’ – from the Imperial Eggs to Emanuel Nobel’s snowflakes – had a specific purpose that was largely separate from its price. Fabergé’s productions were almost always gifts, circulating between the spouses, lovers, siblings, cousins, friends and allies who constituted the gilded classes and crowned heads of early 20th-century Europe. Within this world, snowflake brooches and flowers of white quartz were ideal prompts for conversation, and the originality of Fabergé’s creations meant that they could effectively develop, demarcate and define the often complex relationships between giver and recipient. For the Romanovs, increasingly withdrawing into private life in response to political crises, these relationships were above all familial, and, as a result, markedly inward-looking. Alexandra Feodorovna’s eggs were displayed alongside a motley collection of knick-knacks of varying value, and a selection of family portraits and personal mementoes, behind a corner sofa in the intimate ‘Mauve room’ of the secluded Alexander Palace. In 1908, Fabergé’s Easter Egg ‘surprise’ was a miniature gold and enamel replica of the same Palace, Nicholas and Alexander’s favourite residence, its windows, like the Winter Egg, made of rock crystal. In common with many of the eggs presented to Alexandra, the ‘Alexander Palace Egg’ was adorned on the outside with portraits of her five children.

The Alexander Palace Egg (1908), Henrik Wigström for Fabergé. Moscow Kremlin Museums.

It was appropriate, then, that Fabergé’s international dominance should have resulted from a familial relationship. The Empress Maria Feodorovna had been born Princess Dagmar in the quiet court of King Christian IX of Denmark, and her elder, favourite sister, Alexandra, had married Edward, Prince of Wales, in 1863. Almost as soon as Maria Feodorovna discovered Fabergé’s work, examples of his ‘small conceits’ began making the annual journey from Russia to England to commemorate various birthdays, Easters and Christmases. It was the thought of Queen Alexandra that enticed Fabergé to London, rather than the more fashionable Paris, when he decided to open his first branch shop outside Russia in 1903.

Originally based in the Berners Hotel, and subsequently in an office at Premier House, 48 Dover Street, the new London branch opened without fanfare. It did not advertise, and until 1911 it had no shop front, guaranteeing its exclusivity. Only those who had previously been introduced to Fabergé knew it was there, and they simply walked upstairs and knocked on the office door. Once inside, they could purchase everything from miniature animals and hardstone figures to smoking paraphernalia, handles for canes, walking sticks and umbrellas, combs and opera glasses, frames, knitting needles and stamp dispensers. Fabergé’s agent in London was Henry Charles Bainbridge, whose memoirs of his time with the firm, together with his sales ledgers, are the source of a wealth of information about the firm’s UK activities; the latter have been combed over by Kieran McCarthy, the managing director of Wartski, and forms the basis for much of the V&A exhibition.

Empress Maria Feodorovna and Alexandra, Princess of Wales, photographed in c. 1900 by W. & D. Downey. Photo: W. & D. Downey/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Maria Feodorovna received the news of the London opening with consternation. ‘Now that that silly Fabergé has his shop in London,’ the now Dowager Empress wrote to her sister, ‘you have everything and I can’t send you anything new, so I am furious.’ Sure enough, both Alexandra and her husband, now Edward VII, became devoted customers of the London branch, and where they led the rest of Edwardian England followed, so that the secluded shop quickly became a node in a network of social relationships: as Lady Sackville, Vita’s mother, famously observed, ‘You meet just everyone at Fabergé.’ Emanuel Nobel was by no means unique in seeing the season’s social events as prompts for luxury gifts. According to Bainbridge, the Russian diplomat Stanislas Poklewski-Koziell would arrive at English country-house parties with two large suitcases ‘loaded with things from Fabergé’. ‘I have no doubt,’ he added, ‘that the ladies of the party scanned the list of visitors with eagerness and […] took care to be present with aprons extended when he shook the tree’.

Poklewski-Koziell’s generosity may have been unusual, but his use of Fabergé was not. The firm’s emphasis on the miniature and on the novel made their products easy to fling in a bag and to pass from one hand to another. It also ensured that part of the purpose of the objects would be fulfilled as soon as the delighted recipient opened the distinctive white holly wood box, and caught sight of a bell push in the form of a crab, a platinum mesh brooch studded with gems to resemble petit-point embroidery, or two agate owls perched on a gold branch. This moment of delight had its fullest expression in the ‘surprise’ at the heart of each Imperial Easter Egg, but Bainbridge insisted there was ‘a gift’ in even Fabergé’s smallest pieces. ‘[H]e instilled a balm into all his work,’ Bainbridge wrote, so that ‘[a]t our first sight of every object […] the music within us responds, ringing out in chords of merriment and melody’.

Frog cigar lighter (c. 1906), Henrik Wigström for Fabergé. Royal Collection Trust. Photo: © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

The art of gift-giving in these circles was to seal relationships between elite members of society, and it was therefore imperative, to avoid embarrassment, that the present itself should allow both parties to believe it had only cost a trifle. In reality, Fabergé’s items ranged in price from £5 for simple silver cases to more than £200 for more elaborate pieces and into the thousands for jewellery but, though the raw materials were reassuringly expensive, designs were carefully refined to ensure the lowest possible outlay. As Bainbridge put it, ultimately ‘it was the expression that mattered’, and royals, in particular, should not be seen to be receiving gifts of money. ‘Go to Fabergé’s,’ Edward VII reportedly told someone who wanted to give him a print of a racehorse. ‘They have a hippopotamus cigar lighter in nephrite. The print is right enough […but] the lighter, I am sure is half the price, and it is amusing.’ It is not certain whether Edward ever got his hippopotamus but in 1906, Queen Alexandra gave him a bright green nephrite frog with diamond eyes, holding a silver-gilt lighter in its open mouth, which she almost certainly had designed specifically for him.

Fabergé’s reported mark-up of between 80 to 100 per cent therefore reflected not just the technical skill of this employees, but also their ability to produce appropriate ‘expressions’, and to respond playfully and intuitively to their customer base. Ultimately, Fabergé’s workers became active participants in the exchanges of gifts woven through elite society. The design of the Imperial Easter Eggs was left entirely to the workshop’s discretion, though there is something of the parlour game in the commission’s three stipulations: designs must be egg-shaped; they must never be repeated, and they should all include the all-important ‘surprise’. In London, Bainbridge studied his customers’ likes and dislikes, and used his findings to inform the ideas he relayed back to Russia. He almost always had a specific onward trajectory in mind for the stock Fabergé returned to him each October. Once the season began in earnest, the London branch kept two maps side by side, ‘one with little flags showing the hoped-for destinations, and the other a blank to be filled in with actual “landings”’. Many of these ‘hoped-for destinations’ were indirect. Such pieces as a monochrome enamel box decorated with a view of Chatsworth were conceived as bait not for the Duke and Duchess of Devonshire, who lived there, but for their friends. They often obliged: Queen Alexandra gave Fabergé’s Chatsworth box to Louise Cavendish, the Dowager Duchess, for Christmas 1908.

Convolvulus (c. 1900), Fabergé. Royal Collection Trust. Photo: © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2021

As a result, while, in the years running up to 1917, Fabergé’s productions were everywhere, few people were truly ‘collecting’ his work. Instead, these objects were passed on, passed down, or used until they broke. The ledgers of the London branch reveal a steady stream of repairs to items left, or passed, idly around. A key exception was Queen Alexandra herself who, at her death in 1910 was found to have (in the words of her daughter-in-law) ‘such a mass of things of all kinds’ as to provide a warning to others, ‘for nothing was ever thrown away in those 60 years!’ Though Vita Sackville-West was publicly dismissive of Fabergé’s clients, she herself inherited many examples of his work from her mother. These include Fabergé’s miniature representation of the convolvulus (popularly known as bindweed), which Lady Sackville had bought at the London branch in 1908, for £35. Its golden stem, supporting engraved nephrite leaves, curls around a white enamel pole in the trademark twisting motion with which this invasive weed smothers every other plant it touches. As an enthusiastic gardener, Vita Sackville-West knew plenty about bindweed: when she first took possession of the dilapidated garden at Sissinghurst, she found the plant had ‘wreathed its way into every support’. ‘Nature run wild,’ she concluded, ‘was not quite so romantic as you thought, and entailed a great deal of laborious tidying up.’ Fabergé’s jade convolvulus removed the need for tidying. Later in life, she reportedly displayed her Fabergé flower studies alongside real flowers in posy holders, fresh from the garden.

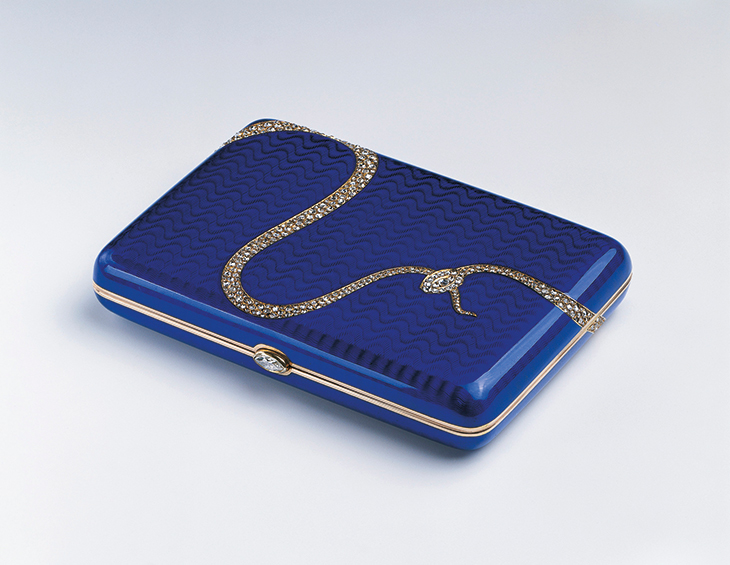

Cigarette case (1908), Fabergé. Royal Collection Trust. Photo: © Her Majesty the Queen Elizabeth II

Vita Sackville-West’s convolvulus was subsequently acquired by Bernard Eckstein. It was purchased from his sale in 1949 as a birthday present for Queen Mary who was at this time busy buying up Fabergé for the Royal Collection (see March 2021 issue of Apollo). Other acquisitions included an art nouveau-inspired gold cigarette case fired with layers of blue enamel over an illusionistic engraved moiré ground, originally presented to Edward VII by Alice Keppel, the king’s favourite mistress, and one of Fabergé’s most devoted clients. After Edward’s death in 1910, and apparently in a gesture of goodwill, the widowed Queen Alexandra returned this ornate love token to her formal rival. Keppel repaid the tribute: after George V’s death in 1936, she sent it back to Queen Mary, who thereby restored it to the family Fabergé. The circularity of the gift is a neat equivalent to the motif that runs across the case in hundreds of tiny diamonds: the ouroboros, or snake biting its own tail. Originally a symbol of ‘eternal love’, this glittering serpent evokes Fabergé’s status as part of the warp and weft of an elite world whose connections were endless. The evocation had particular resonance for the British royal family. After the 1920s, Western markets were increasingly welcoming Fabergé items that had seeped out of what was now Bolshevik Russia in the pockets of smugglers and exiles, or via dealers working with the ‘Antikvariat’, a department of Lenin’s Ministry of Trade specifically designed for the profitable disposal of art. In 1933, at Cameo Corner in the Burlington Arcade, George V found the ‘Mosaic Egg’, which Alma Theresia Pihl had designed for Alexandra Feodorovna the year after the Winter Egg (Fig. 5). It had been confiscated by the provisional government in 1917, and sold by the Antikvariat for 5,000 roubles. He presented it to his wife.

‘Faberge in London: Romance to Revolution’ is at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, from 20 November– 22 May 2022.