Some years ago, the American artist Eric Fischl, who made his name in the 1980s painting suburban scenes that thrum with repressed desire, familial tension and sexual unease, told Apollo: ‘There’s a point at which you’re looking at a painting and you’re no longer looking at it as the artist who made it […] You’re looking at it thinking, what the fuck is going on here? Who are these people and what do they want?’

Fischl seems less mystified by his latest series, Bathers, for which the artistic process was so lengthy that he had plenty of time to get acquainted with his pieces. But that isn’t to say there were no surprises along the way. Originating in Fischl’s playful experiments with Tilt Brush, a virtual-reality painting app that allows you to make paintings in three-dimensional space, the Bathers series involved Fischl’s 3D figurative paintings being converted into bronze sculptures by the Stroud-based foundry Pangolin Editions; Fischl applied paint to these sculptures, which were then installed at Victoria Miro Venice. Fischl describes the works as ‘a painter’s idea of sculpture’, but if they symbolise the melding of two mediums, they also embody an unexpected harmony between Bronze Age materials and the capabilities of digital technology. The website of the extended reality company Vortic, which collaborated with Fischl on the process, offers a glimpse of the strange, unique works that resulted.

Fischl, who is 76 and lives in the Hamptons, spoke to Apollo via Zoom about the experience of making Bathers, the art that makes him queasy, and The Church – the community arts centre he established with his wife, the artist April Gornik, in 2020.

Installation view of Lady with Red Hat (2023) by Eric Fischl at Victoria Miro, Venice. Courtesy the artist, Victoria Miro and Vortic; © the artist

What are the best and worst things about Tilt Brush?

The best thing, which I think is also one of the best things about virtual reality, is that my experience of it was not dissimilar to when I used to do LSD. It created a sense of wonder and awe. It has to do with the fact that your body knows it’s in two different places simultaneously. That creates a kind of hyper-awareness – you start to look at every detail of everything. I found that heightened sense very exciting; it brought a lot of that sense of wonder back.

On the negative side, even though it’s technologically advanced, it’s an unsophisticated painting tool. It can’t match the inventiveness or effects that actual painters have historically brought to bear. For example, it has an eraser tool, but it erases the entire brushstroke. With painting and drawing, you can carve with the eraser, which gives you another dimension to shaping form.

Tilt Brush doesn’t have transparencies or blending either. The work that I’ve done reflects its capabilities: an impressionistic, direct attack, made up of lots of brushstrokes, trying to describe something physical.

Could you talk me through the process?

You’re wearing goggles; inside the goggles is a set of parameters that you work within. One of the things I like about Tilt Brush is that it involves your whole body, very much like painting. You’re still occupying a space and you’re making gestures, large and small, moving around, moving through.

You have these two hand tools. One gives you a choice of strokes or marks and a choice of colours. The other is the painting tool itself, with which you can control the breadth of a brushstroke. So you click on the paint tool, make a gesture, and there’s this floating brushstroke in the middle of infinite space, which is fabulous. And then there’s another, and another. I kept it simple because it was such a new technology and I didn’t know what the hell it was.

Do you get much say in the bronze casting process or is that entirely down to Pangolin?

I didn’t want a lot of say in what is a highly complicated process, but I did have a yes or no. And we did make some changes and adaptations. There were also practical problems to consider: if the piece is suspended too far out from the wall, say, it might tip forward and rip part of the wall out. So then you shorten the space between the wall and the figure, but in doing so you create other problems: the image collapses. So you have to recut the bronze and restage it.

Eric Fischl painting one of the works from Bathers at Pangolin Editions, Stroud. Photo: Steve Russell Studios; courtesy the artist, Victoria Miro and Vortic

How did the process affect your approach to line and colour?

It has yet to be seen. The colours I usually use in my paintings aren’t nearly as high-keyed or opaque as the colours that Tilt Brush offers, but there’s something attractive about the Tilt Brush palette. It moves you into a less dramatic psychological space than conventional painting, where you can be more subtle with colouration and create deeper moods and more sophisticated light.

The process has a fluidity to it. Mark-making in VR is fun: there’s no surface behind the gesture, whereas I’m used to the resistance of the canvas. So if I make a brush mark straight up and down on a canvas, it goes straight up and down. But in a reality that has no resistance, when you go straight up and down, the mark you make is an arc, because your arm is a pendulum. And when you stop painting and then start again, you’re no longer in the same plane. So you get these separations that sometimes work and sometimes don’t.

Looking at the finished product, I’m impressed that the way I normally paint translated well. These figures have a palpable physicality, and even though the way they’ve been rendered is more gestural than depictive, they read surprisingly coherently given that the strokes weren’t always on the same plane.

Unlike with paintings, there is a certain remove at work here – other people are involved in the making process. How does that affect your relationship to these artworks?

I view it as teamwork, so I don’t take all the credit. It involves so many different skill sets and ways of pushing a project along that it’s more akin to making a movie than a painting. I find that exciting. The studio can be lonely: you have to keep finding ways to convince yourself that this is worth spending time on. Here, the impetus comes from a team.

I’m very bemused by Pangolin’s approach. They said, ‘The brushstrokes are just digital information. We can make the work as large or as small as you want: we could blow it up to 100 feet high or render it on the scale of jewellery.’ We did end up making a few maquettes for jewellery. Again, this wasn’t premeditated: I never thought, ‘When I get to a certain point in my life, I’m just gonna make some merch.’

Three Women by Pool (2023), Eric Fischl. Courtesy the artist, Victoria Miro and Vortic; © the artist

Which contemporary artists’ work is exciting you at the moment?

Some of what Tracey Emin has been doing lately, with her intensely emotional, expressive, violent drawings of her body in decay from cancer, and how her identity is wrapped up in her femaleness and relationship to her illness. It’s very brave, powerful and inspirational.

There are a lot of Black artists who have never left figuration, and are bringing a vitality and freshness to it that I find very inspiring. Some of them are dealing with political or historical subjects; others are ignoring it and just painting family, friends or strangers, using unusual materials and representational structures. Arcmanoro Niles is one: his paintings are surprisingly high-keyed glazes of domestic scenes. His figures might have pink glitter beards, or orange where the whites of the eyes are. There’s a strangeness to it, but there’s also an exactness to the rendering. He’s someone who clearly understands anatomy as well as the frozen, meaningful moment. His work is very intimate and personal.

From more of a distance, I like Derrick Adams: he’s more patterned and schematic in his rendering, but very smart in terms of what he’s looking at.

So much of your work is highly sexual. Do you think there’s such a thing as an oversexualised painting?

There’s a difference between painting nudes and painting naked people. Nudes are an embrace of the sensual, the pleasurable, of unfettered desires and unselfconsciousness. It approaches a kind of purism, a kind of abstraction. But painting a naked person is painting a body that is stripped of defences. Their relationship to self is more present. The painting becomes about whether or not they are comfortable with themselves. That’s a far more dramatic thing to investigate for me than just painting nudes. With a naked person you have the sexual life of an individual; to put that into a painting is to make public a drama centred around desire and need, and to explore points where your characters are either emboldened or diminished.

So can a painting be oversexualised? I know I’ve seen paintings that have made me queasy. I might even have made paintings where the process made me queasy, but by the time I’d finished I’d come to terms with that.

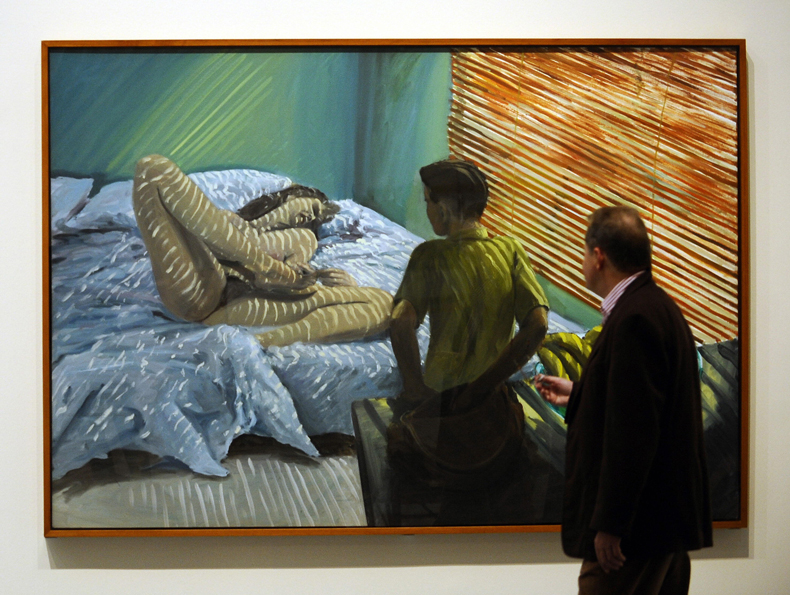

A viewer looks at Bad Boy (1981) by Eric Fischl at a temporary exhibition at the Museum Kunstpalast, Düsseldorf, in 2008. Photo: Volker Hartmann/DDP/AFP via Getty Images

Which artists have made you feel queasy?

Lucian Freud. I don’t mean to insult the entire British sensibility, but I’m going to anyway: the British have a morbid sense of flesh. You see it in Bacon, Freud, even the Pre-Raphaelites: they have such an intense desire to capture every aspect of the physical form in extreme detail that a kind of ambivalence creeps into the obsessiveness. Freud’s painting is almost corrosive: his insistence on painting and overpainting, just trying to find the exact shape of a kneecap or whatever, until the paint gets crusted… it has a push-pull effect on me. Painters like Otto Dix and Christian Schad and a lot of the German painters from the 1930s and ’40s – their work freaks me out, it’s so creepy. Right now, Sarah Lucas is pushing the envelope, with the way the playful vulgarity in her work can tip into a cringe-inducing moment.

Tell me about your community arts centre, The Church. What is happening there?

It’s called The Church because when April and I bought the place, it was a deconsecrated Methodist church. Its programming is intended to be as artistically broad as possible: it’s got dance, music, playwriting and poetry, as well as visual arts and craft-based things. It needs to both engage the community and have a level of quality that elevates the entire artistic experience of the town. We’re trying to find a way to bridge the gap between those who live their lives with no apparent need for art or creativity – who are deeply suspicious of the art world, with its inflated prices – and those artists who create in a kind of language that is less daunting than the esoteric artspeak the public often shies away from.

Right now we have an exhibition by Sara Cochran, a Scottish curator who has been with us since the beginning. This is her swansong: her final exhibition is an all-women show about the ‘debate’ around whether women have a sense of humour. It has some wonderful, whimsical, intense, confrontational and laugh-out-loud stuff in it. And it fits our mission: to find topics that empower people walking through the door.

We also recently had a big conversation between Colson Whitehead, who grew up partly in Sag Harbor and has deep roots there, and Kevin Young, director of the Museum of African American History and Culture at the Smithsonian. Sag Harbor has a very robust and historic Black community and we’re trying to find ways of engaging them.

Interior view of The Church in Sag Harbor, New York. Photo: Michael Heller; courtesy The Church, Sag Harbor

What is the future of the Sag Harbor arts scene?

The problem is that young people can’t afford to live here. Part of the impetus for The Church was to create a residency program so that we could bring them in, even for short periods of time, to help them but also to let us feed off their creative energies. I doubt we’ll be successful in the long run: once artists have generated enough heat in an area, developers come in and everybody wants to live there – to the point where the artists leave and the new inhabitants are living this stupid fantasy of what creativity is. My feeling with The Church was: if people come here looking for creativity, let’s give them the real thing, not some parody or cheap version of it. But as for the future, who knows?

‘Eric Fischl: Bathers’ is at Victoria Miro Venice until 17 August. Once the exhibition ends, the artworks will remain available to view on Vortic’s website.