From the July/August 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

‘I did not want to “invent” pictures, so my sources were in nature, which to me includes everything seen,’ Ellsworth Kelly (1923–2015) once said. That an artist whose work seems to be all clean lines, flat paint and abstract form is rooted in the messiness of life is just one of many contradictions about a figure who doesn’t fit neatly into any box – however neat and boxy his work might seem. He is an American artist with distinctly European influences, whose formative years were spent in post-war Paris. An apparently hard-edged painter who, in fact, rejected much of the cold geometry of abstraction and whose work reflects reality. An atheist whose sudden conversion to a fully abstract style has all the characteristics of a religious epiphany, and who created a transcendent temple of light (Austin, 2018). A minimalist working with what seems to be extreme simplicity of form, shape and colour, yet whose art speaks with a sophisticated aesthetic vocabulary. An artist dedicated to the impersonal, whose work includes deeply sensual curves and homoerotic postcard collages to his long-term partner, Jack Shear.

This year marks the centenary of Kelly’s birth. The milestone is being given the full honours – particularly in the United States, where he is lauded as a titan of his generation. His birthday, 31 May, was declared Ellsworth Kelly Day in an official proclamation by the mayor of New York City, while a city-wide programme to celebrate ‘EK100’ has included exhibitions at MoMA, a sculpture show at Lever House (until May 2024) and tours of his studio in the upstate hamlet of Spencertown. Elsewhere, there’s a large retrospective, ‘Ellsworth Kelly at 100’, at Glenstone in Maryland (until March 2024), which will travel to Paris and Doha; portrait drawings at the Art Institute of Chicago (1 July to 23 October); photographs at Santa Barbara Museum of Art (15 October to 14 January 2024) – as well as shows in Rome and Oslo. Oh, and a fashion shoot in Vanity Fair featuring bright, primary-coloured clothes and accessories in homage to Kelly.

Ellsworth Kelly, photographed on Venice Beach, Los Angeles in 1994

Kelly’s work has endured in part because his pared-back evocations of the ordinary have a timeless quality; he was immune to shifting artistic fashions. Magpie-like, Kelly collected snapshots of everyday life and immortalised them in euphoric shades. He was influenced by, yet ultimately broke away in formal terms from, abstract artists such as Mondrian; was living in Paris during the Abstract Expressionist explosion of Pollock and Rothko and was never a part of it on his return to New York. He took his own unwavering path from the late 1940s onwards. While other artists collided with and diverged from his style, he kept doggedly on. His single-minded quest was to remove all personality from his art – to eliminate the hand of the artist, to make the brushstroke invisible; he wanted to make works that were ‘objects, unsigned, anonymous’, as he put it. And yet, the effect is not clinical or robotic, but the reverse. His way of representing the world is surprisingly expressive; his vast canvases and monumental sculptures are capable of eliciting profound emotional responses.

Writing in the New Yorker after the artist’s death, the critic Peter Schjeldahl described Kelly’s paintings as possessing the ‘suddenness of miracles, and the improbability’. He recalled a Damascene moment experienced 30 years earlier, while standing before one of Kelly’s elongated canvases: ‘The unhurried curve got me. It was like the horizon of a world that made a non-world of all of the space outside it. While my eye was tracing it, I felt a brief, intense flash of something that I can’t name: a perception of perception, perhaps. A short circuit in the brain.’

By absenting any overt self-expression from the canvas, Kelly freed himself up to reflect life in a highly codified fashion. These are not random geometric shapes and pretty colours, but personal responses to a diverse mix of influences and snapshots: architectural details, birds and insects, tribal carvings, Romanesque cathedrals, Byzantine icons, Old Master paintings such as Lorenzetti’s Virgin and Child, Brancusi sculptures, a woman’s green scarf glimpsed in the street, the curve of a young man’s buttocks, stripes of shadow on the steps of a villa in the south of France.

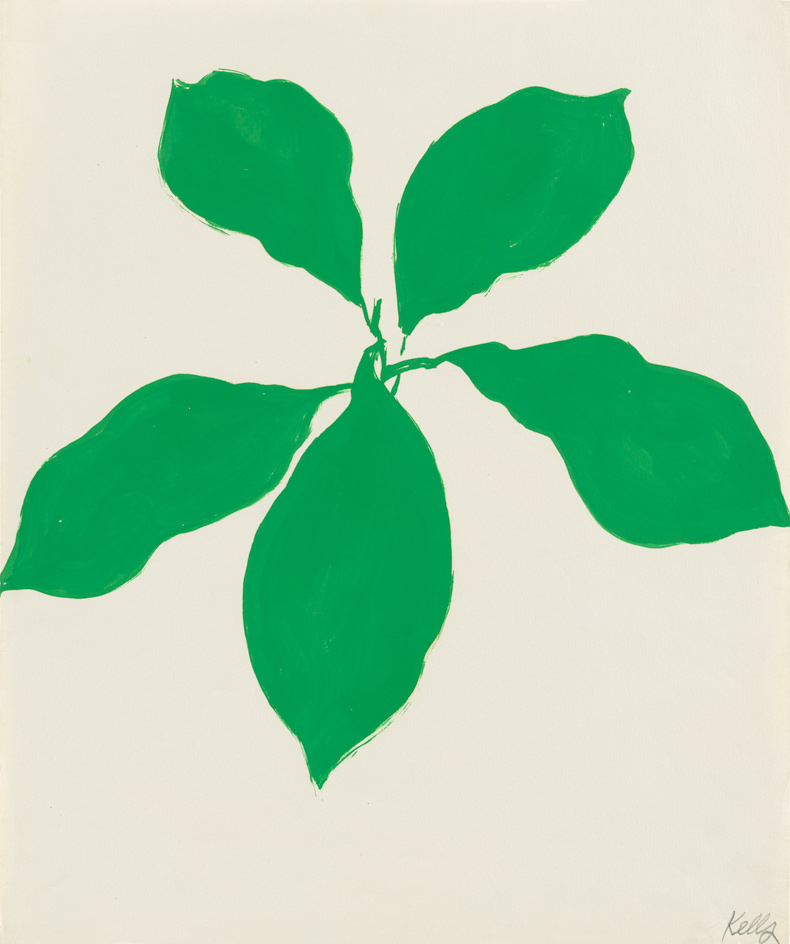

Avocado (1959), Ellsworth Kelly. Private collection

Arguably, Kelly can never quite remove himself entirely from the work – can any artist? During 1953, Kelly’s final year in Paris, he suffered from depression; it feels no coincidence that his work from that period switches starkly into black and white. Rigid parenting, the heavy secret of his homosexuality and the stress of fighting in the Second World War doubtless took their toll, too. ‘In the army, I’d had a kind of nervous reaction, which appeared on my face as a rash, and then there was my stammer,’ he told the journalist Rachel Cooke shortly before his death. One might see his entire career thereafter as a therapeutic process, his fine-tuned calibrations of colour, line and shape sustaining him. As Martin Gayford writes in The Pursuit of Art (2019), Kelly once told him colours and shapes ‘speak to me, I guess’… ‘My eyes are like dictators, I do what my eye tells me and I’ve nourished my eye.’

Born in 1923 in the Hudson River town of Newburgh, New York State, Kelly grew up surrounded by woods and rolling hills. It was birdwatching that sparked his delight in colour; he later recalled solitary walks in a nearby pine forest to see redstarts – small black and white birds with striking orange-red marks – or to a reservoir to observe tonal combinations in the plumage of ducks and geese. When laid up in bed with childhood illnesses, he became engrossed in the detailed ornithological drawings of John James Audubon. ‘When I was a child,’ he wrote in an essay in 1969, ‘I spent all my spare time looking at birds and insects. My colour use […] and the use of fragmentation is closer to birds and beetles and fish than it is to De Stijl or the Constructivists.’ But Kelly’s interest in nature comes not from a botanical or biological perspective, it is about shape and form and the interplay of colour, in the same way as his found perspectives from the man-made world.

We can discern the influence of birds even in paintings as abstract as Blue Panel I (1977), which evokes the peaked crest of a cardinal and the vivid blue of a jay drawn by Audubon; the elegantly elongated rhombus of Red Curve II (1972) is a soaring white and scarlet waterbird coming in to land. The recurring arrow motif in the lithographs Blue Over Green or Orange Over Blue (1964–65), capture Kelly’s obsession with the silhouettes of birds and their plumage, while the pleasingly curvy Yellow Piece (1966), a major conceptual leap into monochromatic sculptural objects, is equal parts lush lemon and cartoon canary. Falcon (1959) abstracts a detail of this bird of prey perched on a post and renders it in carnivorous red.

Yellow Piece (1966), Ellsworth Kelly. Museum of Modern Art, New York

Throughout his career, alongside his paintings, Kelly continued to draw from life – plants, fruit, leaves, flowers – and capture its essence in his work. ‘The drawings from plant life seem to be the bridge to the way of seeing that brought about the paintings that are the basis for all my later work,’ Kelly wrote. Simple linear sketches such as Wild Grape (1960), Locust (1965) or Bunch of Leaves (1970) demonstrate his focus on organic shapes and patterns, while the bright leaf-green of the oil sketch Avocado (1959) has a direct descendant in canvases like the soothing Green Relief Over Blue (2004) or the fruity, fecund Orange Green (1964). Even though these inspirations are filtered down, zoomed in and translated into Kelly’s abstract language, their trace remains.

Despite long stretches as an urbanite, Kelly was never happier than when in nature. It was Paris that formed him, however. Alongside many other artists, he had served in the Ghost Army in Europe – a unit tasked with befuddling Hitler’s troops through camouflage and other visual deceptions – and the experience had a profound effect on both his psyche and practice. As a veteran entitled to study through the GI Bill, he arrived in the French capital in 1948, his intention to investigate modern art ‘at its source’. He would spend six years in Paris, immersing himself in its rich resources, meeting artists such as Brancusi, Arp and Giacometti and travelling widely to European cities, cathedrals and coasts.

Although early work honoured Picasso and Klee, on a trip to see their work at the Palais de Tokyo in 1949 Kelly found himself more transfixed by a triptych of windows than by the art inside. From then on, he wanted to recreate these found compositions. As the art historian Sarah Whitfield writes, he wished to ‘free the shape from its ground, to place it on the wall, and treat it as an object in its own right’. Conceptually speaking, Kelly owes more to the ready-mades of Duchamp than the canvases of Mondrian. He would sketch interesting shapes he found in buildings, shadows, reflections and plants, then blow them up in scale and render them in blocks of bright paint. Therein lies the power of Kelly’s work: that so much can be imagined from it by the viewer, and so much buried within it by the artist. Yet the work itself is secretive, bathed in silence; at once deceptively simple and slightly out of reach.

Falcon (1959), Ellsworth Kelly. Private Collection

He would get out to the French countryside, too, sometimes staying with friends at a villa in Meschers-sur-Gironde on the west coast. His painting Meschers (1951), is an apple-green and azure blue rendering of a nearby forest that recalls his wartime razzle-dazzle camouflage work, while predicting striking colour combinations to come. Similarly, yet in black and white, the collage work Cité (1951) conjures up the play of dark shadows between whitewashed buildings under a high midsummer sun. The tricolour Train Landscape (1953) conjures up green fields and wheat stubble flashing past a carriage window in sorbet stripes.

After Kelly moved back to the United States in 1954, we can detect the change of light conditions in his work. While the French coast brought gleaming colour, and the soft grey Parisian light inspired pastel or black and white pieces – as seen in the series Line Form Colour (1951) – New York was all acid brights and neon artificiality. Here, his canvases became larger and superficially simpler with, in the words of critic Barbara Rose, ‘shapes so large they cannot be ignored, so sharp they cannot be misunderstood, so abstract they cannot be interpreted with literary associations’. And yet, they are never fully urban. His relief painting Blue Tablet (1962), included in the seminal group show ‘Toward a New Abstraction’ in 1963, yearns for sky and sea. Its overlapping shutter-like panels of contemplative cobalt blue, bisected with shadow, draw you in and keep you out all at once.

In 1970, Kelly left Manhattan for Spencertown, upstate New York, where he made a vast 15,000-square-foot studio from a disused theatre. As he told Vanity Fair in 2012: ‘I did not want windows, only skylights. I chose my painting wall as it has the best morning light.’ After an often-miserable 15 years in the city, he was relieved to move closer to the wide horizons of his childhood. In later works such as the leaden Curved Grey Panel (1977), Blue Curve (1994) or the monumental sculpture White Curves (2001), we see him stretching out in the landscape and soaring skyward, the open wings of his boyhood birds never far away. As well as continuing to produce art right up until his death, Kelly’s other great accomplishment was giving back generously to this rural community, through quiet charitable donations and investing millions in youth art education – something that had been so important to him as a boy.

Kelly is perhaps best known for the eight rainbow-like Spectrum pieces that punctuate his career, created between 1953 and 2014. Ranging from easel-size to a monumental installation nearly 50 feet long, they vary in intensity, as if dialled up or down electronically, but each thrums with pure prismatic pigment – giving jolts of colour association to the viewer. In fact, they’re not rainbows or the Newtonian spectrum of seven shades: they always start and end with yellows, and work up and down the chromatic scale in 12, 13 or 14 stripes. Nevertheless, they have a universal quality that constitutes the most all-encompassing vision of Kelly’s colour aesthetics. And one is reminded of the colour wheels of childhood, which appear to fade to white when spun quickly. As he wrote about Spectrum VIII (2014): ‘These colours come from a palette that has interested me since I began investigating colours at the beginning of the 1940s.’ All of Kelly’s career in colour is contained within them and, as such, all of ‘life’ – from the stained glass in Chartres cathedral to the scarlet wings of a songbird.

Thomas Calvocoressi is a writer and sub-editor.

For details of exhibitions dedicated to Ellsworth Kelly, visit the foundation website.

From the July/August 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.