The Egyptian film industry of the 20th century has a powerful hold over the collective imagination of the Arab world. Like Paris of the belle époque or Downtown New York of the 1980s, it is spoken of with wistful sighs and reverent tones among its initiates. The comedies and dramas of the Egyptian silver screen depict a bygone age of mid-century glamour. And, just as Paris at the turn of the century had the posters of Alphonse Mucha and Toulouse-Lautrec (now adorning the walls of a certain type of French bistro), Egyptian cinema produced its own world of promotional art.

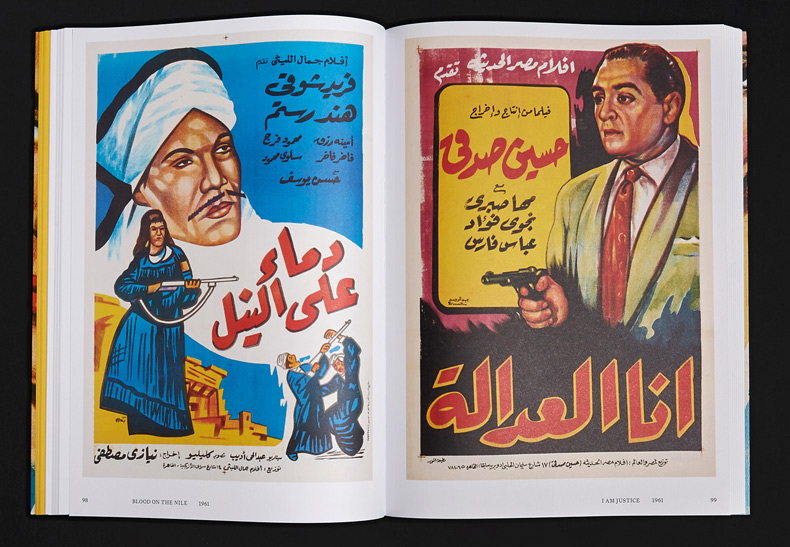

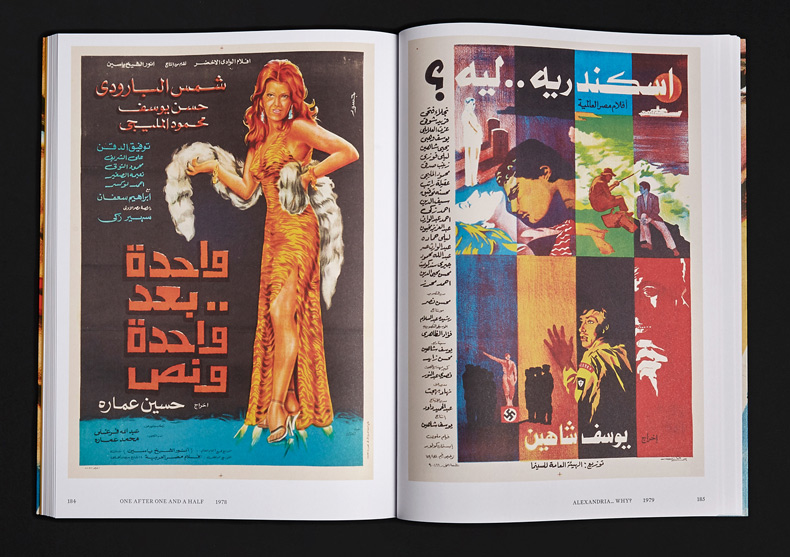

Moving Pictures Painted presents an elegant pictorial history of the Egyptian film poster from 1932 to 1996 in the form of 200 individual examples. Their striking designs were hand-painted by a small group of artists who quickly developed a very distinctive style. The posters captured everything from the epic to the erotic, via the comic and melodramatic. They also chart the history of modern Arabic culture more broadly. An introduction by the film scholar Joseph Fahim makes the only slightly exaggerated claim that ‘movie posters were the dominant pictorial force in Egypt for more than 70 years’.

From Moving Pictures Painted: 200 Posters from the Golden Age of Egyptian Cinema (CentreCentre)

The majority of these posters are from the collection of Thomas Hill, whose ‘PosterArc’ holds around 100,000 posters from 150 countries. This Egyptian section is just a small part of a larger whole, but it includes some of the biggest films and most recognisable stars of the 20th century. There are classic musical films of the 1930s, when Egypt’s cinema industry was first taking off, screwball comedies of Ismail Yassin from the 1950s, the elegant checkerboard poster of Youssef Chahine’s Alexandria… Why? (1979) and many of Adel Imam’s early starring roles from the 1980s. As well as Egyptian films, we see the idiosyncratic takes on the Hollywood and Bollywood movies that played in Egyptian cinemas.

This is not a comprehensive history of the Egyptian film poster. It lacks some of the classics of the genre, such as the poster for Shafiqa al-Qibtiyya (1963), which Egyptian collector-scholar Sameh Fathy identified as a turning point in the art. It also includes slightly random selections; the last poster featured – for the movie Crash! (1996) – is an almost exact copy of the American version.

From Moving Pictures Painted: 200 Posters from the Golden Age of Egyptian Cinema (CentreCentre)

By the end of the book, there is a sense that not everything has been fully explained. The poster for Long Live Love (1938) bears the signature of the artist Gassour, who was born in 1925. Unless he was a particularly precocious 13-year-old, he must have done it later (but when and why?). One of the introductory essays suggests it was made for a rerelease in the 1940s (but which one and what do we know about it?). Confusingly, another introductory essay attributes the same poster to Ragheb, the artist of the 1938 original, despite the signature. The poster for Togo Mizrahi’s Thousand and One Nights of 1941, is given a date of 1964. Is this because it was made for a 1964 rerelease? It is not clear.

This is more than pedantic nitpicking. If we cannot tell the dates of the posters (they do not print the year anywhere on them) how can we full understand their history and their development? Secondly, the lack of publication details obscures what an interesting collection this is. The book advertises itself as a national history of the Egyptian film industry, but details on posters also refer to places in Syria and North Africa. Of the first 20 posters, eight bear the logo of Mabrouka Films, a company set up in 1950 to distribute Egyptian movies in French North Africa. These posters were not printed in Cairo, but at the Imprimerie de la Cinématographie française in Paris. These posters tell the story of a transnational film culture.

This is more than pedantic nitpicking. If we cannot tell the dates of the posters (they do not print the year anywhere on them) how can we full understand their history and their development? Secondly, the lack of publication details obscures what an interesting collection this is. The book advertises itself as a national history of the Egyptian film industry, but details on posters also refer to places in Syria and North Africa. Of the first 20 posters, eight bear the logo of Mabrouka Films, a company set up in 1950 to distribute Egyptian movies in French North Africa. These posters were not printed in Cairo, but at the Imprimerie de la Cinématographie française in Paris. These posters tell the story of a transnational film culture.

This book could set its sights much higher than it does. Film posters did not only form the artistic language of 2oth-century Egypt; with a little more work, the book could show how they were a pictorial history of the entire Arab world.

Moving Pictures Painted: 200 Posters from the Golden Age of the Egyptian Cinema, designed and edited by Patrick Fry, is published by CentreCentre.