‘There was an Old Person of Nice’, ‘There was a Young Lady of Norway’, ‘There was an Old Man on the Border’. Over and over, Edward Lear’s poems flourish a tantalising possibility before the reader: that place and personality might intersect, if only for an arbitrary moment. However, as an exhibition at the Ikon Gallery, Birmingham, demonstrates, the ways in which landscape shapes identity were an obsession for Lear that extended beyond poetry. Ikon brings together a wide selection of Lear’s occasional sketches and watercolours, many of which are shown in public for the first time. As Matthew Bevis, one of the curators of the exhibition, observes in the catalogue, while ‘many of these pictures were aides mémoires, references, trials for future work […] they were also something more: a way for Lear to inhabit and question his experience, and to live in and beyond the moment’. As visitors pass from room to room, they are given the opportunity to look in on Lear’s lifelong habit of painting himself into existence. Or, as Lear put it in a letter in 1862, of converting ‘tangible facts, recollections & past times as it were into pictures’.

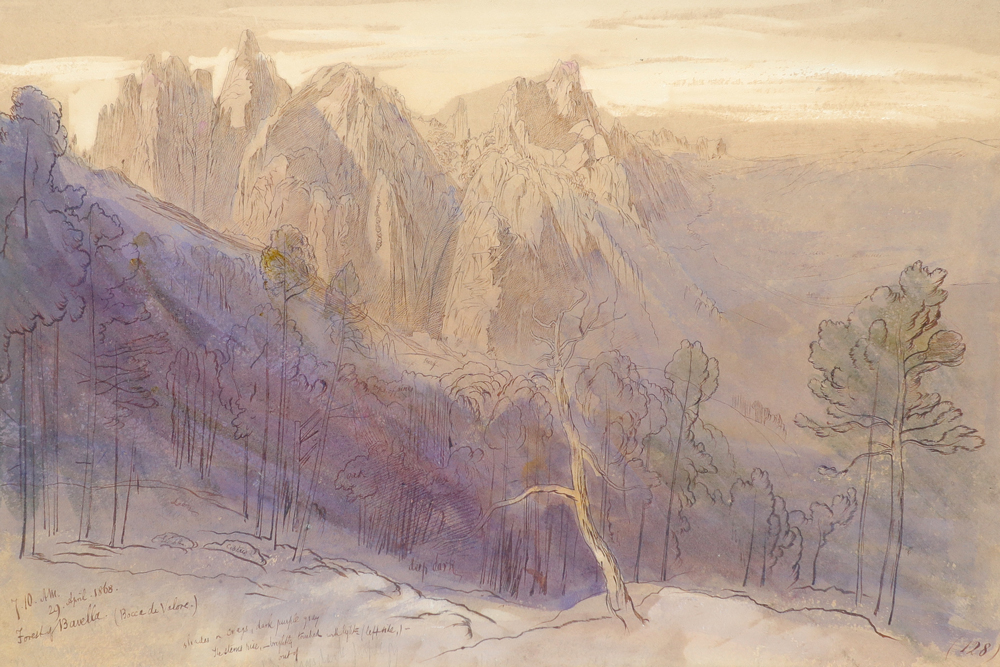

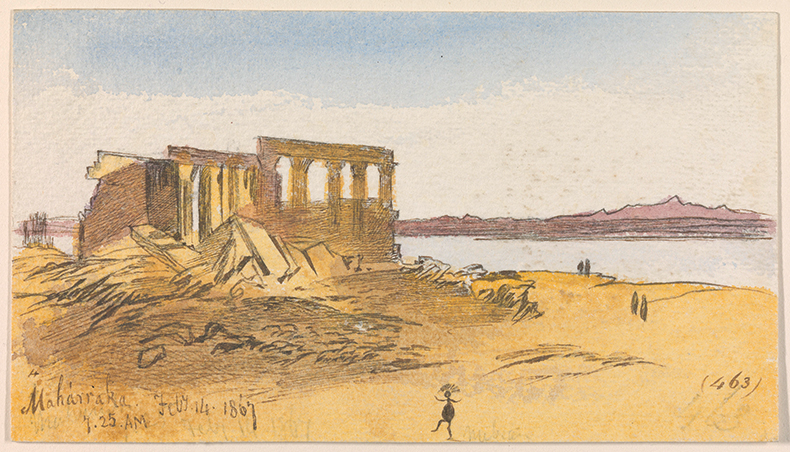

Many visitors to this exhibition will come looking for Lear the exuberant writer of nonsense verse. They will find instead a set of beautiful, if sometimes conventional, 19th-century watercolour sketches. There are occasional flashes of the Lear we know best: a merry, rotund figure capering at the margins of one of four pictures of Maharraka, 14 February 1867, or insouciant nonsense misspellings in one or two notes-to-self: ‘oker redstripes’, ‘gray rox’. In spite of these rare moments of ebullience, however, individual pictures rarely reveal Lear as we might expect to find him. Yet this is arguably a strength of an exhibition which shows one of the most famous figures of the 19th century in a new light.

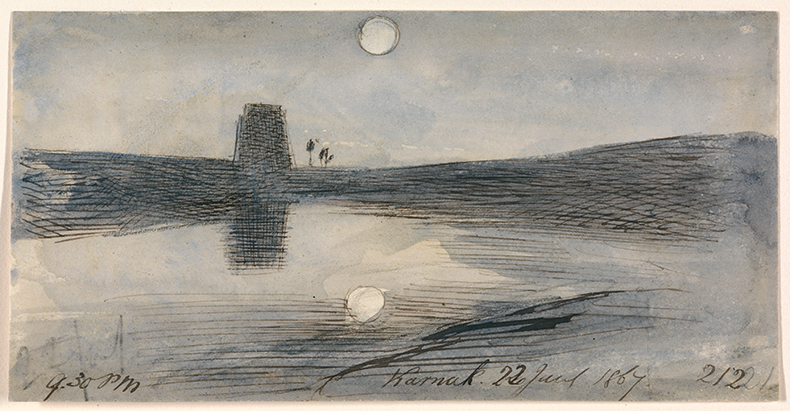

Karnak, 9.30 pm, 22 January 1867 (1867), Edward Lear. Yale Center for British Art, New Haven

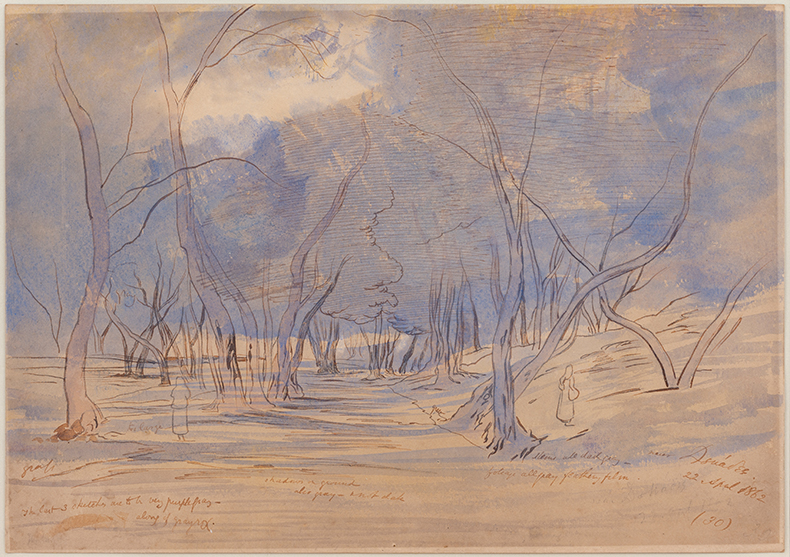

Lear often thought of himself as a creature of travel. As he observes in another letter, ‘If you are absolutely alone in the world, & likely to be so then move about continually & never stand still’. The landscapes on display at the Ikon are often lonely ones, usually devoid of figures. When we do see people, as in A View near Doukades, 22 April 1862 or Ootacamund, 7 October 1874, they are themselves usually alone, turned away from the painter. Often sketched in outline only, and washed over with watercolour, these figures threaten to disappear into their surroundings.

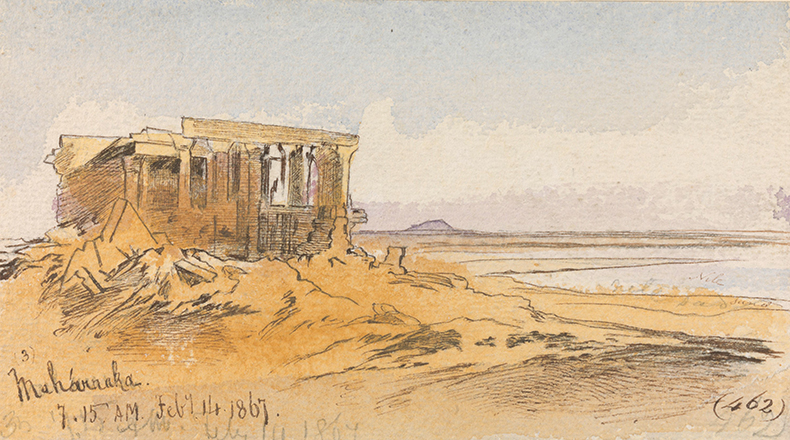

By arranging this exhibition chronologically, the curators emphasise time as a recurrent theme of Lear’s landscapes. But this show offers more than an opportunity to see Lear’s changing style across the years. The intricate interplay of time and place as Lear experienced it can be seen on a minute-to-minute basis: almost every one of Lear’s sketches is meticulously dated and timestamped. As such, the viewer can watch the sunrise pivoting about a landscape, as in the sketches of Maharraka, made at 7.15 am, 7.25 am, 7.30 am, and 7.35 am on a single day.

Maharraka, 7.15 am, 14 February 1867 (1867), Edward Lear. Courtesy Yale Centre for British Art, New Haven

Maharraka, 7.25 am, 14 February 1867 (1867), Edward Lear. Yale Center for British Art, New Haven

There’s a delicate sense here that Lear measures what changes against what endures. Lear was capable of great accuracy with his pen but also of what the curators characterise as an almost impressionistic rapidity and immediacy. In some works, line and colour seem almost incidental to each other, coordinated vaguely as if viewed through two sets of eyes, as in the View near Doukades. (The effect is reminiscent of one of Lear’s humorous self-portraits in which spectacles spring wilfully away from his eyes.) This may have something to do with Lear’s famously bad eyesight or with his working process: he would look briefly at a scene through a monocular device and then sketch it from memory. But it also suits the sense that these images are not static, but rather take place in time and over time. For instance, in two views of Khani Kastelli, Crete, both apparently completed at 7 am, even the stones seem to shift and change from moment to moment; a looming boulder to the right of the canvas either slumps or straightens itself up, depending on the order in which you look at the pictures.

A View near Doukades, 22 April 1862 (1862), Edward Lear

This effect heightens over the course of Lear’s painting life and as the viewer progresses through the exhibition. We lose a sense of distance and scale, present in images such as Bay at Ragusa, 1866, in favour of flattened views such as Galle 19 November 1874 or Kandy 4/6 December 1874. In these works, mushroom-like forms appear to have attained the dimensions of human beings (though it’s hard to tell), and massive bamboo shoots look like delicate blades of grass. It is Lear’s intricate management of time that makes these pictures appear as works in progress, or perhaps in process, even more than is usual in occasional watercolours. They announce that they are part of a process of perception, recollection, anticipation, while also allowing the viewer a sense of what endures through all this transformation.

These fresh and illuminating perspectives on Lear are made possible through the scholarship of the curators, Matthew Bevis and Jonathan Watkins. Lear completed an estimated 9,000 pictures during his 50-year working life, and it is astonishing to witness the narrative of those years emerging clearly through the selection on display here, drawn from museums and archives around the world. Because this narrative becomes apparent through comparison, repetition, revision, recurrence, and change, it is crucial to see these paintings as a group, and it is a testament to the deftness of Bevis and Watkins that they so vividly achieve a sense of the processes and patterns shaping Lear’s pictorial life. In an essay in the exhibition catalogue, Adam Phillips notes that the precision timing of the painting makes them like photographs, but perhaps it might be better to think of them as cinematic. The Lear we meet here lives in the spaces between moments: a figure of transformation and unceasing movement.

‘Edward Lear: Moment to Moment’ is at the Ikon Gallery, Birmingham, until 13 November.