‘An artist must bear a special responsibility,’ wrote the painter and draughtsman Charles White. ‘He must be accountable for the content of his work. And that work should reflect a deep, abiding concern for humanity.’ That was in 1978, one year before White’s death and 16 years after Andy Warhol hypnotised New York with a soup can. In the current age of glib ironists demanding to be taken seriously, the White retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art can’t help but provide a kind of calm, firm comfort. Walking through the exhibition, you have the rare experience of encountering an artist who affirmed his responsibility to the public. Throughout his career, White was constantly trying to decide how best to use his talent to celebrate the dignity of other black Americans.

This mission led White, as a muralist for the Works Progress Administration in the 1940s, to paint black workers, activists, journalists and musicians. Later on, it inspired prints depicting prominent African-American figures like Bessie Smith, Frederick Douglass, and his close friend Harry Belafonte. A self-portrait from 1935 hints at the quiet confidence that propelled him through this career: his mouth curls into the faintest smile; his eyebrows are raised high, wary yet open. Like his hero Goya, White had an astonishing gift for faces, which allowed his best work to appear intimate and semi-mythic at the same time. Even in his grandest murals, where all sense of scale seems to wash away, the figures’ eyes and mouths remain sharply expressive; they’re individuals with their own wills, not flotsam in the currents of ‘progress’.

Five Great American Negroes (1939), Charles White. Collection of the Howard University Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Photo: Gregory R. Staley. © The Charles White Archives

It was crucial for White to learn how to paint black faces with precision. One way to interpret his early work, in fact, is as an attempt to rescue his race from centuries of visual cliché – the hoards of ‘uncles’, ‘mammies’, and ‘pickanninies’ doing whatever their bigoted creators ordered. By 1938, the year White graduated from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, he had digested the works of Alain Locke, whose sponsorship of ‘The New Negro’ was, at its core, a directive for blacks to take control of their own images, in art as in politics. A similar plan drove White’s decision, upon graduating, to found an arts centre on Chicago’s South Side, where he’d grown up. The centre flourished, in part because opportunities for black artists in the ’40s were so meagre – before the Art Institute, White had his admissions to two schools revoked after the administrators found out they’d inadvertently accepted a black student.

The ’40s were also the last time in American history when the government devoted a significant amount of money to paying artists – at the height of the Great Depression, the Works Progress Administration alone sponsored painters, writers, actors, and musicians to the tune of (can it really be true?) half a billion in today’s dollars. The WPA, in its partnership with White’s arts centre, commissioned his earliest major mural, Five Great American Negros (1939). The five – voted on by the readers of the Chicago Defender, the city’s largest black newspaper – include an artist (the blues singer Marian Anderson), a scientist (George Washington Carver), an educator (Booker T. Washington), and two activists (Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth). To these, White adds a sixth, collective hero: a column of former slaves gathered behind Truth, curving off toward the horizon.

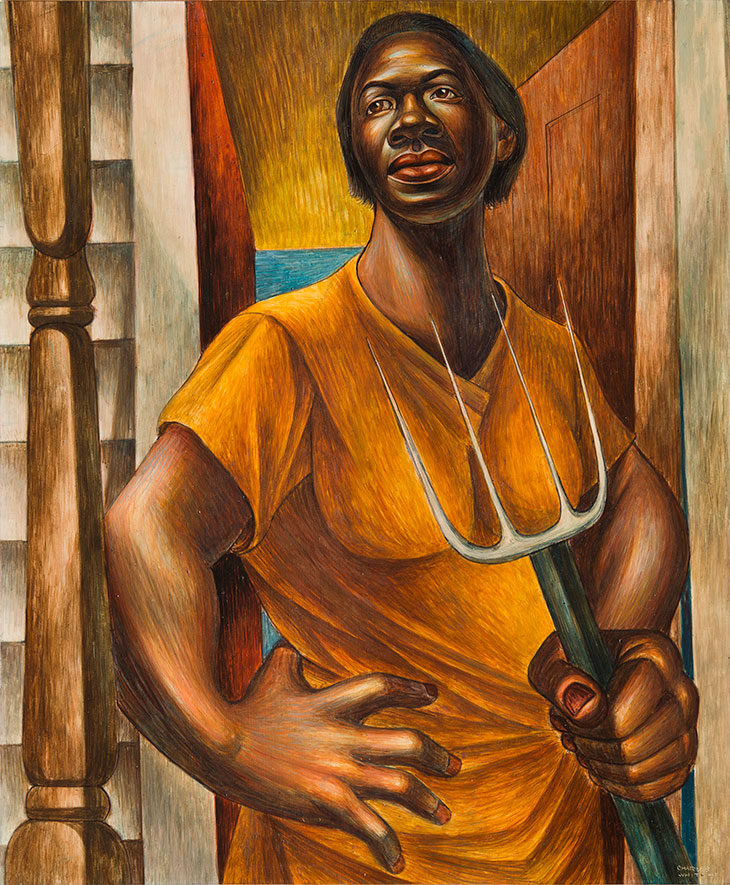

Our Land (1951), Charles White. Photo: Gavin Ashworth. Courtesy Jonathan Boos; © The Charles White Archives

The term ‘collective hero’ is often used in discussing early Soviet propaganda, and indeed White’s was a long romance with Marxism, in which he (and Langston Hughes, Paul Robeson, and Richard Wright) saw an alternative to an American strain of racism that had become hopelessly intertwined with capitalism. For many years White was a member of the American Communist Party and the John Reed Club, and he briefly edited New Masses, America’s principal Marxist journal of the ’30s and ’40s. His work in the decade following the Second World War, like a lot of Red art of the time, alternated between accessible, realist portraits of suffering proletariats and awestruck depictions of the Great Men whose spirits would lead the way to victory. Seen more than half a century later, these works seem tamer and more dogmatic than what preceded them or what would follow. One finds the same formula in them again and again: a strong, humble worker, shown in three-quarter profile, staring up and out beyond the frame as if waiting to inherit the earth.

It would be a stretch to say that White was ignored in his own lifetime, but he was no superstar. He supported himself by teaching college art courses. The first works of his that MoMA saw fit to accept were a handful of minor prints from 1970. Art museums’ loss may have turned out to be art lovers’ gain, though: without the luxury of dining out on his reputation, White kept working until the end. His work from the mid ’60s onwards, after he’d settled in Los Angeles and begun teaching at the Otis Art Institute, was easily some of his best. The different factions of the Civil Rights movement, reeling from the murders of their leaders, were split on how to go forward; there were also, quite possibly for the first time, black Americans who felt that they had transcended race (O.J. Simpson comes to mind). White responded to these developments in images that were wilder and more open-ended in their conversation with the viewer, rejecting the Woody Guthrie wistfulness of their predecessors. The rotting America of Birmingham Totem (1964), Dream Deferred II (1969) and Wanted Poster Series #17 (1971) may have to burn before it can be rebuilt.

Black Pope (Sandwich Board Man) (1973), Charles White. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo: Jonathan Muzikar, The Museum of Modern Art Imaging Services. © 1973 The Charles White Archives

General Moses (Harriet Tubman) (1965) may be the very best of White’s dozens of portraits of Harriet Tubman. Squatting on a rock, glowering straight out of the frame, she’s not a saint, as in some of the earlier renderings, but a creature of the earth itself. Nat Turner, Yesterday, Today, Tomorrow (1972), completed shortly after the death of Martin Luther King, shows the rebel preacher as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. These two works set a tone for the final decade of White’s career, in which the hierarchies of the Social Realist period dissolve and are replaced by commoners without leaders, commoners who might be secret saints, and leaders who might be their own followers. His masterpiece from this period, Black Pope (Sandwich Board Man) (1973) – inspired by a Leonard Freed photograph – shows a man with an unreadable expression walking under a cross, wearing a sign labelled ‘NOW’. Is he a saint or a lunatic? Is the cross attached to his hat, or is it floating above him somehow? What, and when, is now?

‘This register where beauty, perfection in form and execution, can be described as divine.’ That’s what the painter Kerry James Marshall, White’s student at Otis, had to say about Black Pope. It’s hard to disagree with him, yet important to notice that divinity doesn’t bring clarity here. The subject of this glorious enigma never reveals his true nature – you wonder if the painter himself had any idea. Perhaps it’s only right that, after decades of teaching and producing beautiful, sometimes didactic images, White reached new artistic heights when he admitted that he didn’t have all the answers.

‘Charles White: A Retrospective’ is at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, until 13 January 2019.