Hercule Poirot is now 100 years old, although he never experienced a childhood or an adolescence. Instead he was born by a kind of parthenogenesis, leaping fully formed and middle-aged from the head of Agatha Christie in 1921. The shrewd little Walloon has been poking his nose into criminal set-ups ever since, in 33 novels, 59 short stories and any number of film and television adaptations. While Christie’s other great detective, Miss Marple, inhabited a world of chintz and climbing roses, uncovering the rot at the core of an innocuous English village, Poirot was by nature urban, and urbane. He was also precise, vain, uptight and finicky – the sort of man to wear patent-leather shoes in the Devon countryside, or to take a supply of moustache wax to an archaeological dig.

Photo courtesy ITV

The detective’s exploits ranged across a vast swathe of the 20th century, from his origins as a refugee from ‘plucky little Belgium’ during the First World War (in The Mysterious Affair at Styles) to encounters with the swinging King’s Road set (in Third Girl from 1966). While these adventures were generally given a contemporary setting, in the public mind Poirot is indelibly associated with a glittering interwar world. Other paperback heroes, from Sexton Blake to James Bond, are perennially modernised, sliding forward in time with the passing years: so how did Poirot become preserved in the amber of his art deco world?

Entrance hall of Eltham Palace, Greenwich, in 2008. Photo: Heritage Images/Getty Images

The obvious answer is that many of his most celebrated cases were written in the 1920s and ’30s, and took place in up-to-date environments such as the Orient Express, lavishly furnished in the deco style. (The film from 2017, starring Kenneth Branagh with a great Nietzschean shrub of facial topiary, takes place on a reimagined fantasy version of the train that acquires an austere Bauhaus quality.) But much of the credit for the symbiotic relationship between Poirot and art deco has to go to the makers of the long-running series of ITV dramas starring David Suchet, aired between 1989 and 2013, which have come to be regarded as definitive adaptations. (To celebrate the centenary of Poirot’s first appearance in the UK, ITV has produced an hour-long documentary, presented by Richard E. Grant, dedicated to Christie and her Belgian sleuth.) Right from the opening titles, viewers are plunged into a world of high deco: Suchet’s face is shattered, by means of some very 1980s VFX, into triangular shards reminiscent of Juan Gris’s fragmentary cubism; a steam train straight out of a Cassandre poster rockets past the stylised silhouette of Giles Gilbert Scott’s Battersea Power Station, presumably following the highly glamorous Victoria-to-Clapham Junction rail route. The production team took a conscious decision from the outset that the design would be based on the styles of the mid 1930s, so while Suchet and the other cast members aged a quarter of a century, Poirot himself remained fixed in place, like evidence on a microscopic slide.

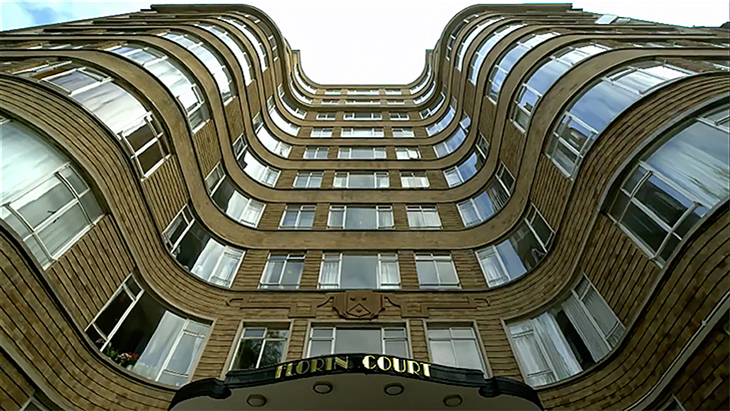

Florin Court in Clerkenwell, which stands in for Whitehaven Mansions, Poirot’s home, in the ITV productions. Photo courtesy ITV

The locations used for the programmes were a roll call of some of Britain’s finest interwar buildings. The opulent Eltham Palace with its circular entrance hall, the austerely authoritarian Senate House at the University of London, the Aztec-influenced Hoover factory on London’s Western Avenue, even Lubetkin’s helter-skelter penguin pool at London Zoo have all made appearances. The ABC Murders is partially set in Bexhill, so naturally features Erich Mendelsohn’s pioneering De La Warr Pavilion (which also pops up in Sarah Phelps’s characteristically liberal BBC adaptation in 2018, starring John Malkovich as Poirot). In some cases, dilapidated buildings needed renovation by the production team, who even went so far as to re-create Eric Ravilious’s lost murals at the derelict Midland Hotel in Morecambe.

The De La Warr Pavilion, Bexhill-on-Sea. Photo: Arcaid/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

The establishing shots of Poirot’s flat in ‘Whitehaven Mansions’ depict the undulating brick-and-glass facade of Florin Court in Clerkenwell. The building is in the streamline moderne style, echoed by the polished walnut and tubular steel of the set designs; ‘the set was 30s modern, not actually Art Deco,’ according to ITV producer Brian Eastman, ‘because Agatha Christie had explained in a profile of Poirot that Art Deco was too flamboyant for him.’ Indeed, the moderne style, with its stark symmetry, is perfectly suited to Poirot’s precision and love of order, while being luxurious enough to accommodate his more epicurean side. The airy, wide-windowed styles of interwar modernism reflected a drive towards a more hygienic way of living – entirely fitting for a man portrayed by Suchet as a virtual obsessive-compulsive.

The Isokon Building in Hampstead, where Agatha Christie lived between 1941–47. Photo: View Pictures/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

The detective’s creator also lived in a high modernist environment – after her London home in Holland Park was bombed in the Blitz, Christie took a flat in the Isokon building, a reinforced-concrete ocean liner in Belsize Park whose residents had recently included Bauhaus émigrés Walter Gropius, Marcel Breuer and László Moholy-Nagy. Christie also wrote both Evil Under the Sun and the Poirot-less And Then There Were None at the striking Burgh Island Hotel in Devon, which features one of England’s best-preserved deco interiors.

It is curious that period art and design should be so integral to the world of Poirot, since detailed descriptions of place are rare in Christie’s fiction. As a writer she was dedicated to plot above all else. So in a way, perhaps it is fitting that such a richly evocative milieu should be extrapolated from little more than a few tiny clues.

‘Agatha and Poirot: Partners in Crime’ airs 5 April on ITV.