‘Today, I must have bought about two-and-a-half thousand objects,’ says Ashish Anand. ‘Postcards,’ he explains with a smile, relaxing in the backroom of his gallery in Delhi. ‘I’m buying anything and everything in Indian art. Yesterday I bought nine very rare books on Tibet.’

From the modest Delhi Art Gallery opened in 1993 by his mother Rama Anand in Hauz Khas – then a funky area of still-quiet Delhi – the business, now named DAG, has expanded to a global brand of galleries, museums, archives, publications and public outreach. While its offices remain in Hauz Khas, DAG’s art spaces are multiplying across India – and the world.

This year, Anish Anand opened a sleek new gallery inside the deluxe Claridges hotel, in the heart of Lutyens’s Delhi, with ‘The Sixties Show’. In that decade, ‘India was less euphoric than the West,’ Anand explains. ‘We had the wars of ’62 and ’65; rationing; the Indian dream was not coming true. The Bombay Progressives were established. Abstraction took hold and a lot of art was sombre, soulful.’ With exceptions, always: Krishen Khanna returned to figurative wildness for his fiery Rider (c. 1960), a highlight of the show. Anand has followed it up with ‘The Seventies Show’ (until 25 January 2020).

Rider (c. 1960), Krishen Khanna

The majority of pieces in his exhibitions come from DAG’s vast stock – Anand airily puts it at around 60,000 on the busy shopping day I meet him. ‘Every single work is for sale, the difference being that some are at a premium because they are rare or special. My ultimate aim is to buy more art.’ When he joined his mother three years after she opened her gallery, he’d already been a businessman but had ‘no understanding about art, never even heard of any artist’. He spotted a lack of support for older living and recently deceased artists and started to buy from their studios, their estates, and even from collectors. ‘The only understanding I had was that there were a lot of artists who had made a big contribution but had not got their due. I simply travelled, met artists, trained my eye. There was no market, but I wanted to buy more and more. That’s the enduring problem!’

Establishing a secondary market, Anand delved deep into India’s 20th-century movements, then those of the 19th century, and further back. ‘Now, we cover all aspects, all parts of the country, all movements, all artists, so we can do deep research.’ The commitment – and carefully modulated sales promotion – is extensive. Each DAG exhibition has an accompanying book with new research, often a hefty hardback. Other publications focus on a single artwork or artist. Oral histories of artists and their works are commissioned as well, and across DAG spaces there are public programmes, which include artist-led talks.

The quantity of stock means Anand can expand in different ways. In its Fuller Building gallery in New York, which opened in 2015, DAG has just given a retrospective to Madhvi Parekh, who is from Gujarat in western India. Anand has been buying her work since the late ’90s and believes the gallery’s New York presence ‘helps promote Indian art in a big way’. In Mumbai, the very specific story of the Madras Art Movement, which emerged in the 1950s–60s from the grip of the colonial art college, recently filled the four-storey gallery of a historic building in the downtown arts district of Kala Ghoda, where DAG arrived six years ago. More like a museum exhibition than a commercial one, it was accompanied by a 500-page book spinning from K.C.S. Paniker’s liberating leadership in the ’40s to contemporary artists such as V. Viswanadhan, known for his bold use of colour and geometry, and S.G. Vasudev, who explores texture and form. Impressive loans from museums in Delhi and Chandigarh and private collections further enriched the show.

Untitled (1972), V. Viswanadhan

Loan-rich shows are not DAG’s only form of collaboration. In Old Delhi, Anand is helping breathe life back in to the historic Red Fort – once home to the Mughal emperors, later a colonial garrison and in recent decades an exercise in abysmal conservation. The Indian government was transforming the disused British barracks into museums and was searching for crowd-pulling use for Barrack No. 4. ‘We tendered, won it, and finished in four or five months,’ says Anand. The Archaeological Survey of India, a government department, cleaned up the elegant building with its lofty rooms ideal for use as galleries. Inside, working with Adrien Gardère (museographer for the Musée du Louvre-Lens’s interior spaces and inaugural exhibitions), Anand established Drishyakala art museum, raiding DAG’s accumulated stock for the works on display.

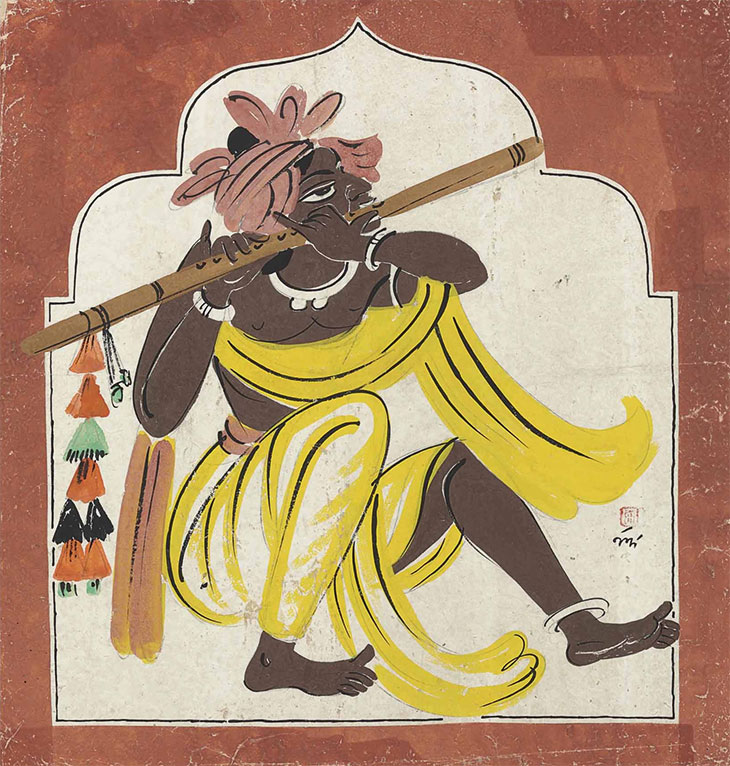

The museum was inaugurated at the beginning of 2019; its first, year-long installation (until 2 Feb 2020) consists of four expansive displays focusing on portraits, popular prints, landscapes by the British uncle and nephew pair Thomas and William Daniell, and the nine key artists named in the ’70s as ‘national treasures’ – from Raja Ravi Varma to Jamini Roy. The prints include one of Nandalal Bose’s landmark posters for the Congress party meeting at Haripura, Gujarat, in 1938, commissioned by Mahatma Gandhi to create images that celebrated rural life and drew the attention of those it depicted. ‘We needed more spaces to display and democratise this art,’ Anand says. ‘As a company it’s not about simply selling art, it’s about showing art and creating an understanding. Entry is free. It’s all about the visitor.’ Around 3,000 people come each day, many apparently making their first visit to a museum and having their first encounters with art.

Flute player (1937), Nandalal Bose

The opening of Drishyakala coincided with another partnership with the Indian government, this time the Ministry of Textiles, to create a crafts museum outside Varanasi, the Hindus’ most sacred city and one renowned for its weaving. Above two floors displaying textiles and crafts, DAG has opened a revolving exhibition drawn from its own warehouses celebrating the city known as ‘Eternal Banaras’. As so many professional and amateur artists were inspired to record the sacred city, whose riverbank is daily suffused in serene light, DAG has an abundance of paintings, prints and photographs to choose from.

Further collaborations just this year include one with the Fondation Giacometti to study the global history of modern art and India’s place in it, another with the Wallace Collection in London for a current show about Indian artists patronised by members of the East India Company. Next year, DAG launches three more projects in Delhi: a flagship gallery in the diplomatic area of Chanakyapuri, a space in the business-heavy suburb of Okhla offering art advice and close study of artworks, and another art-filled barrack at the Red Fort. Ashish Anand also recently took his art shopping to the next stage: he bought Jamini Roy’s house in Kolkata. Will he live in it? ‘No! It will be the first single-artist museum in India.’