‘But who wants object-lessons about vanished races? What one wants is contact. The Etruscans are not a theory or a thesis. If they are anything, they are an experience.’ It was just such an experience that led D.H. Lawrence (1885–1930) to write Etruscan Places, his perceptive travel account of Etruscan art and civilisation which was first published posthumously in 1932. Lawrence had previously written memorably about his travels in Italy (in Twilight in Italy, 1916, and Sea and Sardinia, 1921) and Mexico (in Mornings in Mexico, 1927) and many of his voyages during the last 10 years of his life – to Ceylon, Australia, Mexico, New Mexico, and the South of France – directly influenced his novels and poems. But Etruscan Places remains one of the most haunting of Lawrence’s travel books and one in which the art of this lost civilisation vibrantly comes to life. Exactly 90 years after Lawrence visited, I travelled to Etruria to follow in his footsteps and, with a first edition of the book in hand, set out to look at Etruscan art and architecture through the lens of his writing. Over five days, in April 2017, I visited every central Italian site described in Etruscan Places, considering how Lawrence’s views and interpretations can still inform a visit to today’s archaeological locations, and shed light on Etruscan art.

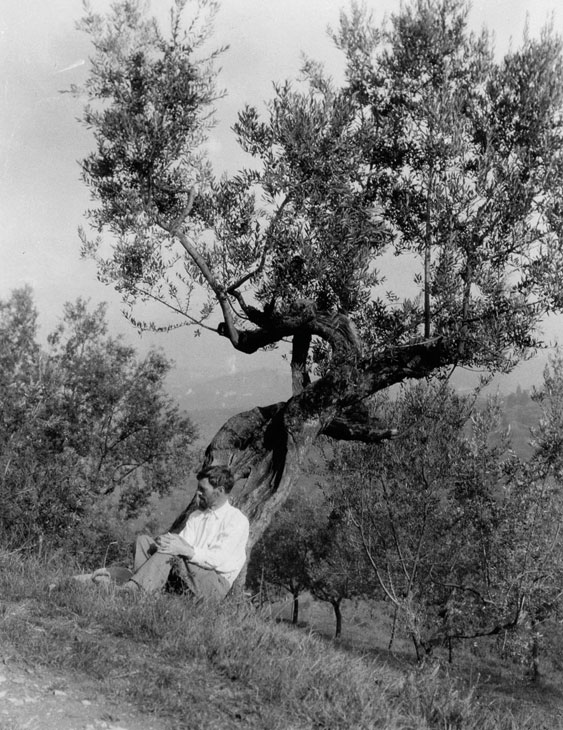

D.H. Lawrence beneath an olive tree at Villa Mirenda, San Polo Mosciano, c. 1926–27. Manuscripts and Special Collections, The University of Nottingham

In 1926, D.H. Lawrence moved to Villa Mirenda, near San Polo Mosciano on the outskirts of Florence. He had travelled extensively outside Europe between 1922 and 1925, and now took refuge in Tuscany, together with his wife Frieda, with whom he had shared an unconventional and tumultuous relationship since 1912. Between 1926 and 1928, Lawrence was at work on Lady Chatterley’s Lover, and in April 1927, between the second and third (and final) version of the manuscript, he set out to visit a number of Etruscan sites together with the American painter Earl Brewster (1878–1957). The trip provided the material for a series of six essays, which were subsequently transformed by Lawrence’s London publisher, Martin Secker, into a book printed two years after Lawrence’s death. Lawrence was a pioneer when it came to the topic. Etruscan art had been little studied in England, and throughout the trip, Lawrence’s guide was George Dennis’s Cities and Cemeteries of Etruria, first published in two volumes in 1848, a book that he had read years before and that he often refers to. Like Lawrence’s essays, Dennis’s book focused on both the archaeology of the sites and the present state of each location, and so acted as both scholarly account and guidebook.

Among the most notable features of Lawrence’s book is his constant juxtaposition of the Etruscans and the Romans. The book opens with a polemical statement: ‘The Etruscans, as everyone knows, were the people who occupied the middle of Italy in early Roman days, and whom the Romans, in their usual neighbourly fashion, wiped out entirely in order to make room for Rome with a very big R.’ Educated in Victorian England, where the neoclassical ideals of Winckelmann had defined the taste for Graeco-Roman antiquities for more than a century, Lawrence saw in the Etruscans a sense of freedom and brilliance that he contrasted with the Roman desire for conquest. Etruscan art became for him the yardstick against which to measure the art of the past and of the present. Giotto and medieval Italian sculptors ‘seem to have been a flowering again of the Etruscan blood’, while ‘one Etruscan leopard, even one little quail, is worth all the miles of’ John Singer Sargent, who Lawrence somewhat unfairly, but true to his own taste, describes as ‘utterly uninteresting, a bore’. In 1927, Italy was already beneath the yoke of Mussolini’s Fascist regime, and Lawrence’s view of ancient Rome is clearly a thinly veiled parallel with the state of contemporary Italy. The debilitating effects of the First World War on the Italian population appear throughout the book, and Fascism remains a potent presence. Lawrence reports how, in Civitavecchia, a man insistently asked him, as a foreigner, for his passport, which maddened the writer; and in the centre of Volterra large posters inscribed ‘Mussolini ha sempre ragione’ were pasted in the streets. Throughout the trip Lawrence was often welcomed with a Roman salute: ‘Why don’t they discover the Etruscan salute, and salute us all’etrusca!’

By 1927, Lawrence knew he was dying. The last five years of his life, from 1925 until his death in 1930, were marked by the onset and quick advance of tuberculosis. Though only in his early 40s, Lawrence had a dying man’s grasp of life, with a morbid interest in the malaria that was then affecting large areas of the Maremma in the midst of the Fascist reclamation which had seen the area develop into a holiday centre for affluent Italians. Lawrence’s awareness of mortality pervades the book: ‘In the tombs we see it; throes of wonder and vivid feeling throbbing over death. Man moves naked and glowing through the universe. Then comes death: he dives into the sea, he departs into the underworld.’ Lawrence abandoned himself to rhapsodical descriptions of the vitality of the Etruscan universe: ‘To the Etruscan, all was alive: the whole universe lived: and the business of man was himself to live amid it all. He had to draw life into himself, out of the wandering huge vitalities of the world.’ Many pages follow a mystical vision of the great soul of the cosmos, making the Etruscans into a model for the modern ideal man as Lawrence imagined him.

Lawrence’s descriptions of the Italian landscape are lyrical. He travelled across northern Lazio and the Maremma, ‘one of the most abandoned, wildest parts of Italy’, recounting his interaction with local inhabitants. He paid meticulous attention to the wild flowers at each site – particularly the ‘pink and rather spasmodic’ asphodel, which for him epitomised the ‘reckless glory’ of ancient Greece. While, 90 years on, I found the asphodels already withered by the end of April, I recognised most of Lawrence’s wild flowers. More dramatically, I was subjected to the same meteorological vagaries that he experienced: a ‘sunny April morning’ in Cerveteri; the wind blowing ‘stiffer and stiffer’ in Tarquinia; ‘gloomy’ Vulci; and ‘cold, almost icy’ Volterra. Other things have changed, of course: almost a century later, accommodation and food in all the locations has invariably improved, and the small towns that Lawrence describes – Palo, Ladispoli, and Montalto di Castro – have developed into sprawling modern centres.

Lawrence provides striking descriptions of the characters that he encountered in Etruria: there is Albertino, the 14-year-old Dickensian manager of Gentile’s hotel in Tarquinia; the young German archaeologist ‘who looks as if he’d had vinegar for breakfast’; and Luigi and Marco, the maremmani who serve as guides to Vulci. Equally colourful are his accounts of architectural ruins: the bridge at Vulci ‘in the sky, like a black bubble, most strange and lonely, with the poignancy of perfect things long forgotten’ or the Porta dell’Arco in Volterra, ‘with that peculiar weighty richness of ancient things’, where ‘three dark heads, now worn featureless, reach out curiously and inquiringly, one from the keystone of the arch, one from each of the arch-bases, to gaze from the city out into the steep hollow of the world beyond’. He views and describes Etruscan masterpieces in unforgettable ways: the sarcophagi in Tarquinia like ‘the dead crusaders in English churches’ or the vases of black bucchero ware at the museum in Palazzo Vitelleschi, which ‘open out like strange flowers.’

The Porta dell’Arco, Volterra. Photo: © David Lyons/Alamy Stock Photo

In the book as published, Lawrence describes four Etruscan sites: Cerveteri, Tarquinia, Vulci, and Volterra, with a few pages on the National Archaeological Museum in Florence. It seems likely, however, that he planned to write about a larger number of places, including the National Etruscan Museum at Villa Giulia in Rome. Each Etruscan archaeological site could be seen with a local guide, and tombs were explored with the aid of acetylene lamps. In 2017, by contrast, the archaeological park at Vulci has an average of 20,000 visitors per year, and the necropolis in Tarquinia up to 100,000. The two central chapters of Etruscan Places focus on the painted tombs of Tarquinia, forming almost half of the volume. Lawrence describes 16 tombs and their frescoes in detail, mentioning that ‘either twenty-five or twenty-six’ were then visible. Of those discussed by Lawrence, only six are regularly open to the public today; five are closed, and five can be visited by appointment. However, in Tarquinia today, 21 tombs are habitually open, of which 16 were discovered after the publication of Lawrence’s book, largely during a substantial archaeological campaign in the 1960s. The most recently discovered tomb at Tarquinia, the Tomb of the Blue Demons, was found in 1985 and was opened to the public this spring. Each tomb is now visible only through a glass door, which guarantees the conservation of the delicate frescoes; frustrating as this may sometimes be, it is imperative for the preservation of these wall paintings, following the onset of mass tourism.

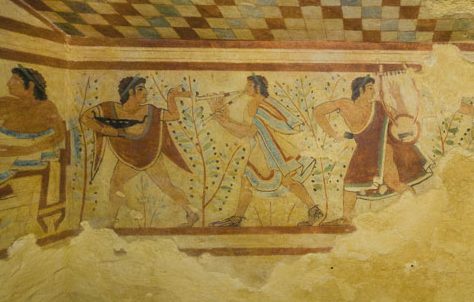

Frescoes in the Tomb of the Leopards, Necropolis of Monterozzi, Tarquinia. Courtesy Mibact. Soprintendenza Archeologia, Belle Arti e Paesaggio per l’Area Metropolitana di Roma, la Provincia di Viterbo e l’Etruria Meridionale

The tombs and frescoes are portrayed by Lawrence in inspired terms. Examining these paintings ‘you cannot think of art, but only of life itself, as if this were the very life of the Etruscans, dancing in their coloured wraps with massive yet exuberant naked limbs, ruddy from the air and the sea-light, dancing and fluting along through the little olive trees, out in the fresh day’. Haunting passages describe the Tomb of the Augurs, with prodigious figures performing ‘the mourning gesture, strange and momentous’, and the Tomb of the Bulls – with a detail described by the guide as ‘un po’ di pornografico!’ Lawrence is quick to justify such details. For him they ‘are not two little dirty drawings. Far from it […] The drawings have the same naïve wonder in them, as the rest, the same archaic adult innocence of complete acceptance.’

Frescoes in the Tomb of the Augurs, Necropolis of Monterozzi, Tarquinia. Courtesy Mibact. Soprintendenza Archeologia, Belle Arti e Paesaggio per l’Area Metropolitana di Roma, la Provincia di Viterbo e l’Etruria Meridionale

Most interesting is Lawrence’s attitude to museums holding Etruscan artefacts. In 1927, he visited the museums in Rome and Florence, and the book includes descriptions of the small museums at Palazzo Vitelleschi in Tarquinia and the Museo Etrusco Guarnacci in Volterra. He was persuaded that ‘it is a great mistake to rape everything away from its setting, and huddle it together in the “great centres” […] Museums anyhow are wrong. But if one must have museums, let them be small, and above all, let them be local. Splendid as the Etruscan museum is in Florence, how much happier one is in the museum in Tarquinia, where all the things are Tarquinian, and at least have some association with one another, and form some sort of organic whole’. It is an attitude that resonates today, and not least because the famous Euphronios Krater – illegally excavated from the Greppe Sant’Angelo necropolis in Cerveteri at the end of 1971, and sold to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1972 – was returned to the Italian government in 2008. For four years the extraordinary masterpiece was displayed at the Villa Giulia in Rome, but since 2012 it has provided the centrepiece of the small museum in Cerveteri, a short distance away from the tomb in Greppe Sant’Angelo where the niche in which it was discovered is still visible among the camomile and thistle flowers.

Euphronios Krater (c. 515 BC), Euphronios. Museo Archeologico Cerite, Cerveteri

Lawrence’s views on museums in the ‘great centres’ are a reminder of how extensively Etruscan artefacts had been dispersed in previous centuries. The Inghirami Tomb, for example, one of the most impressive funerary complexes discovered in Volterra, and containing about 50 of the characteristic carved alabaster sarcophagi from the area, was discovered in 1861 by the brothers Jacopo and Ludovico Inghirami. In 1899, the contents of the tomb were transferred to the National Archaeological Museum in Florence, where a life-sized replica of the tomb was built under the museum’s garden, and the sarcophagi were displayed in the facsimile of the tomb. Damaged during the flood of 1966, the tomb was restored afterwards, but is currently closed, like most of the garden of the museum, for lack of staff. Lawrence commented on how the treasure from the Regolini-Galassi Tomb in Cerveteri had already been moved to the Museo Gregoriano Etrusco at the Vatican, and when he attempted to visit the François Tomb in Vulci, he writes, he ‘tried in vain to get in. Short of smashing the lock, it was impossible.’ He would have not seen much in any case, since the extraordinary cycle of frescoes from the tomb had been detached in 1863 by Prince Alessandro Torlonia and moved to Villa Albani in Rome. When, in 2004, the cycle of frescoes was lent by the private owners to the museum in Vulci for three months, the exhibition attracted 35,000 visitors, almost double of what the entire site attracts in a year.

The Inghirami Tomb, recreated with artefacts from Volterra at the National Archaeological Museum in Florence in 1899. Photo: Scala, Florence; courtesy Ministero Beni e Att. Culturali e del Turismo

Today, a visit to the necropolis of Banditaccia in Cerveteri or that of Monterozzi in Tarquinia confirms Lawrence’s view in 1927: ‘there is a queer stillness, and a curious peaceful repose about the Etruscan places I have been to, quite different from the weirdness of Celtic places, the slightly repellant feeling of Rome and the old campagna, and the rather horrible feeling of the great pyramid places in Mexico, Teotihuacán and Cholula, and Mitla in the south; or the amiably idolatrous Buddha places in Ceylon.’ Remarkably, though, the archaeological parks of Cerveteri, Tarquinia, and Vulci have witnessed a renaissance in the last 90 years, having been well maintained and opened to a wide public through the work of the Soprintendenze. More structures than ever have been protected and made accessible, in locations where tombs are abundant (more than 400 survive at Cerveteri and almost 6,000 have been discovered at Tarquinia – only three per cent of which were decorated with frescoes). As much as the idea of visiting these sites in relative solitude with acetylene lamps sounds appealing, it is a great accomplishment that they are now suitably managed and studied. New excavations are occasionally carried out, most recently in the area of the Tomb of the Sea Waves in Cerveteri, in 2016.

Notwithstanding the enhancements to these archaeological parks and their increased visitor visitors, the sites described by Lawrence still preserve that evocative quality described in Etruscan Places. With all their idiosyncrasy and enigmatic qualities, Etruscan works of art remain enthralling as the relics of a long lost and still deeply mysterious civilisation. Lawrence was right when he noted that ‘there is a haunting quality in the Etruscan representations. Those leopards with their long tongues hanging out: those flowing hippocampi: those cringing spotted deer, struck in flank and neck; they get into the imagination, and will not go out.’

From the July/August issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.