Jan van Huysum’s Fruit Piece (1722) is an exhilarating combination of precision and indistinction. The tumble of fruit and flowers that spills up the canvas perplexes carnation with pomegranate, grape and plum with iris, leaves and buds with full-blown bloom. Its composition is baroque, an organic echo of the twists and implications of cloth and cloud in paintings of the Ascension or Assumption. The seasons are confused as spring and harvest coincide. Twining tendrils of sweet pea, the prinked frills of kale and carnations, and the reticulated pattern on the skin of the lurking melon counter the plump spheres of grapes, peaches, plums, and hazelnuts, confounding the elements in a luscious tangle. Yet the rendering of detail is exquisite. The blebs of the raspberries and the grapes are bravura executions of these tests of painterly skill. Even the points at which the fruit turns to mush are precise. Despite van Huysum’s minute attention to texture and luminosity – he allowed no visitors to his studio, to preserve the secrets of his technique of layered glazes – the independence of the individual fruits, nuts, and flowers is subordinate to the flourishing assemblage.

Fruit Piece (1722), Jan van Huysum. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Nothing seems further from the sober composition of Clara Peeters’ Still life with Cheeses, Almonds, and Pretzels, another Dutch still life painted approximately 110 years earlier, in which the simple forms of individual objects retain their separate identities. An example of an ontbijtje, a breakfast piece, it presents staple fare of the early 17th-century Netherlands. The canvas – probably cut down by several millimetres on each side – and the stone ledge that supports the meal are crowded. The arrangement is horizontal rather than vertical, additive rather than clustering. While van Huysum’s fruit and flowers are placed before a classical urn and a bucolic scene, here a black background allows the objects to stand starkly, illuminated by a strong light from the left, beautifully evidenced in its varying effects on the surfaces it touches: the planes of the cheeses, the glaze on the earthenware, and the multiple reflections in the glass.

Still Life with Cheeses, Almonds, and Pretzels (c. 1615), Clara Peeters. Mauritshuis, The Hague

While van Huysum’s fruit and flowers seem fresh from nature (even if a nature mysteriously flowering and bearing fruit at once), everything Peeters depicts has been made or in some way treated: not just the plates, Venetian glass, and the earthenware flagon, but the dried raisins and figs, the shelled almonds, the grapes pressed into wine, the baked bread and twisted pretzels. This is a modest bounty of human endeavour. Instead of a spiralling turret of fruit and flower, we are met with a stack of cheese.

Such stacks were a common feature of the paintings of tabled meals produced by painters in Antwerp and Haarlem in the early part of the 17th century, the subject of an upcoming exhibition, ‘Slow Food’, at the Mauritshuis (9 March–25 June), which coins the term maaltijdsstilleven to bring the works together, and which will feature several of Peeters’ panels including this one. Peeters and her contemporaries Pieter Claesz, Hans van Essen, Floris van Dijck, Floris van Schooten, and Jacob van Es frequently repeat the motif. The ontbijtjes differ from the more familiar still-life tropes of ripened fruit and floral displays, or the extravagant and exotic meals – pronkstilleven (luxury still lifes) – that were typical later in the century. One of the figures on the handle of Peeters’ knife depicts Tempa, or temperance; the relative modesty of these works belies the embarrassment of riches associated with the Dutch Golden Age. Nonetheless, in their treatment of detail and interest in the concealed sources of animation, the ontbijtjes and van Huysum have something in common.

The cheese stacks dominate the paintings in which they appear, in terms of architectural composition, placement, colour. Peeters depicts a half round of what is probably young Gouda; a wedge of a contrasting dark cheese, older and probably an Edam coloured with parsley; and a sheep’s cheese perched on the Gouda, on which a plate with curls of butter precariously rests. The details of texture and surface are beautifully executed. Each flake of butter has been ploughed by a serrated knife; its colour varies with shade and thickness. The Gouda shows a hole and a plug, where a piece has been removed for testing. The cracks, cuts, pocks, and air holes are minutely observed; as is the discoloration and hardening around the edges, and the occasional insinuated blossoming of mould.

Peeters reused a very similar configuration four times, and the general pattern of three cheeses of differing sizes, colours, and ages is common among her contemporaries. These cheese stacks have proved difficult to interpret, however. They fail to participate in the tropes of vanitas that are the typical resort of readings which approach still life for symbol and allegory. Instead, commentators remark on their scrupulous realism and the lavishing of aesthetic relish and minute attention on the stuff of the everyday. More recently, Julie Berger Hochstrasser has proposed that the cheeses, closely identified with particular areas of the Netherlands, celebrate the dairy bounty of the region, its prowess in making cheese, and the economic power that came from its export, a humble forerunner of the economic and colonial power celebrated in pronkstilleven.

One temptation is to reach for a context in the religious preoccupations of the place and period. Pretzels are a Lenten bread: made without the forbidden foodstuffs of dairy produce or eggs, their crossing shape is supposed to represent hands in penitential prayer. Dried fruits, similarly, are associated with Lenten fasting. The wine and bread might signify the relief of the fast in the elements of communion. Cheese and butter, however, flagrantly transgress the church’s prohibitions. The canvas might thus be thought to stage an oblique fight between carnival and Lent, less literally depicted than the famous painting of the theme by Peeters’ contemporary Pieter Bruegel the Elder. Pieters, like Bruegel, was probably active in Antwerp – the blade of the knife depicted in this and several other canvases shows a silver mark of the city in the shape of a hand – which, since its recapture for the Spanish crown in 1585, had been separated from the independent states of the Protestant Low Countries to the north. Since Reformers had done away with the Lenten restrictions, so that butter and cheese might be consumed throughout the year, the conjunction of cheese and pretzel might take on a political and theological cast.

The motif of the stack of cheese, however, also appears with other foods where such associations cannot apply, and in any case is much stranger on the eye than a domestic context would suggest. In the Still Life with Cheeses, Almonds, and Pretzels, the semicircle of Gouda, the wedge of Edam, and the hexagon of sheep’s cheese present an interplay of geometries, in two and three dimensions, made more complex by the facets and fissures caused by the knife. The hacked face of the Edam in particular is suggestive of the enigmatic polyhedron in Dürer’s Melencolia I (1514) – an image that Peeters may have known, given the wide circulation of his prints and imitations of them in the Netherlands in the late 16th century and beyond. While Peeters clusters her cheeses so that the Edam occludes part of the Gouda, in the anonymous Still Life with Cheese, Fish, and Onions (c. 1615) and in Floris van Dijck’s Still Life with Cheese (c. 1615), the cheeses are stacked as a tower, the smallest, oldest, and darkest cheese a precarious crescent rocking on the top. The cut faces of the rounds resemble something geological. The knife’s intervention has created striations and crenulations in the surfaces, splits and fissures that invest the soft and perishable stuff with the monumentality of rock.

Still Life with Cheese (c. 1615), Floris van Dijck. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

This effect of estrangement is partly a product of the scrutiny of the everyday that still life always encourages, offering a licence to the viewer to contemplate the form and meaning of commodities and comestibles of common experience. But it is also the case that cheese was a more mysterious substance in this period than we might expect. Its process of formation was at once familiar, practised by uneducated ‘cheese-wives’, and a mystery unavailable to physical explanation. Why milk curdled and bound when mixed with rennet was not adequately understood, and thus lent itself to speculative and imaginative engagement. It had been used in the early church as a figure for the mysterious formation of the incarnate body of Jesus in Mary’s womb, and appears in the Renaissance as a recurring image for Creation. Carlo Ginzburg’s The Cheese and the Worms (1976) investigated the world-view of a 16th-century miller, known as Menocchio, who believed that the world and its inhabitants were created when chaos ‘curdled like a cheese, from which later great multitudes of worms were born’. In an English manuscript now held in Chetham’s Library, Manchester, an anonymous 17th-century writer used cheese’s curdling, coagulation, and hardening as an extended metaphor for ‘the generation of eternal nature’, prompting a contemporary reader to ask in the margin, ‘is cheese rational?’, and ‘is cheese animal and do we eat it alive?’

Still Life with Cheese, Fish, and Onions (c. 1615), artist unknown. Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam

These questions might seem ridiculous or satirical, but that it would have been easy to think that cheese had something animate about it. Daniel Defoe, visiting Stilton on his Tour through the Whole Island of Great Britain in the 1720s, remarked that ‘it was a town famous for cheese, which […] is brought to the table with the mites, or maggots round it, so thick, that they bring a spoon with them for you to eat the mites with, as you do the cheese’. This diet of worms might turn our stomachs, but it was not a cause of dismay for Defoe (and indeed there are still cheeses today, such as the mimolette or commissiekaas of northern France and Flanders, which deliberately use mites to produce their textured crust). The production of worms and mites from cheese was both a common feature of the table and a subject of scientific debate. Like the making of cheese itself, how these tiny creatures came to be was not understood. Lacking evidence for the eggs from which such wriggling things were born, or any procreative act to start them, natural philosophers, such as Peeters’ Middelburg contemporary Isaac Beeckman, believed they sprang forth by spontaneous generation. Margaret Cavendish wrote in her Observations upon Experimental Philosophy (1666) that ‘such insects, as maggots, and several sorts of worms and flies, and the like […] have no generator of their own kind, but are bred out of cheese, earth, and dung, etc.’ Cheese as such was potentially animate, indeed might have the capacity for will and imagination: ‘maggots in a cheese’, Cavendish suggested, ‘are not made by patterning or imitation, […] but merely by a voluntary figuring’. It was not until the later 17th century, when English and Dutch figures such as Henry Power, Robert Hooke, and Antoni van Leeuwenhoek began publishing their investigations with microscopes, that it was proved that cheese mites were born less spectacularly from eggs; and not until the 19th century that the belief became general.

The twin Netherlandish fascinations with what Svetlana Alpers has called ‘the art of describing’ in 17th-century scientific observation and painting thus extended to cheese. It was Dutch artisans and natural philosophers who invented, improved, and popularised the microscope. Cornelis Drebbel of Middelburg began manufacturing them in London in the 1620s. When his relative Jacob Kuffler brought one to Rome in 1622, it was to demonstrate the magnification of fleas and cheese mites. The mites of cheese were likewise among the first creatures studied by Power, Hooke, and van Leeuwenhoek. There is thus an unexpected connection between the presence of stacks of cheese, and of closely observed insects, in Dutch still life.

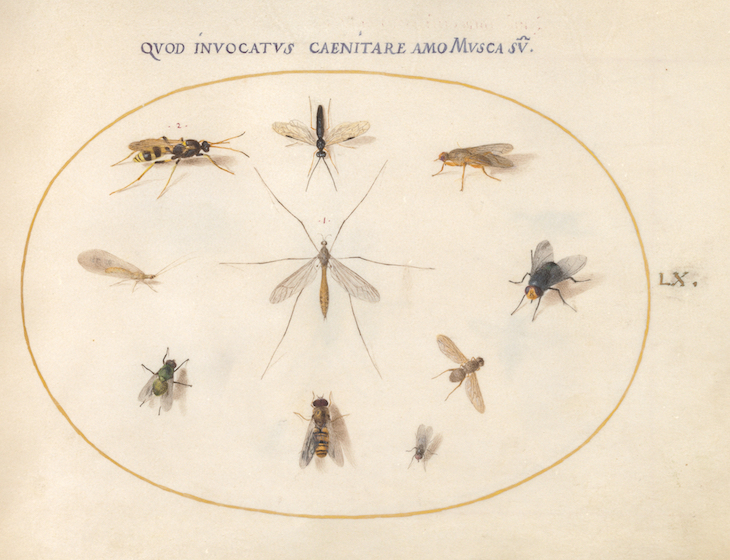

Both artists and those interested in the natural world were encouraged in the period to observe and admire insects, since they demonstrated the curious ingenuity of the creating hand of God, crafting symmetries and elegancies on a tiny scale, beyond the capacities of human makers. The wonder was of course enhanced after the deployment of microscopes, but the depiction of what Henry Power called ‘Living-exiguities’ for delight in their intricacy was already a trope. Joris Hoefnagel, a Flemish painter and draughtsman, illustrated detailed observations of plants and insects in a series of books later published as engravings by his son as the Archetypa studiaque patris (1592). The Archetypa, as scholars have shown, were used as a source and pattern book for the creatures which appear repeatedly, apparently through spontaneous generation, in Dutch paintings of the period: caterpillars, beetles, snails, wasps, and grasshoppers, as well as the ubiquitous fly.

Flies in Renaissance painting generally were a trope of trompe l’oeil. Giorgio Vasari had told a story in which Giotto, still a boy and studying with Cimabue, painted a fly on the nose of one of Cimabue’s figures so realistic that the older artist repeatedly attempted to brush it off. The tale partially accounts for the solitary fly which so often perches on a surface in still lifes: in Peeters’ Still Life with Fruit, Dead Birds, and a Monkey, for example, a fly squats on a grape, while one of van Huysum’s peaches also plays host to an insect guest. The encouragement to observation, however, and interest in the sources of life and animation even amid what the French would come to call nature morte, are equally significant prompts.

Still Life with Fruit, Dead Birds, and a Monkey (date unknown), Clara Peeters. Private collection

In both the Archetypa, and in a plate of the Animalia Rationalia et Insecta, a book of watercolours he prepared in the 1570s and 1580s for Rudolf II of Prague, Hoefnagel accompanied his images of flies with a saying from Erasmus’s Adagia (1500): ‘Quod invocatus caenitare amo Musca sum’, ‘because I love to dine though uninvited, I am a fly’. The fly is not just a figure of trompe l’oeil, but also an uninvited guest at a feast. In a still life, it thus mirrors the uneasy position of the viewers, tempted by a meal they should not eat. In the case of van Huysum’s Fruit Piece, identifying with the fly also draws the viewer to a level of attention below the flourishes of the overall composition. From that perspective, the local animation of the painting becomes obvious. The surfaces of fruit and flower are alive with tiny teeming insect life, initially invisible in the riot of colour and upward motion distracting the eye from activity at a lower scale. There are many uninvited guests here: ants besieging the punctured plum, scaling the peaches, lost in the folds of the carnations; wasps and flies of various kinds touring the grapes and apricots.

Animalia Rationalia et Insecta (Ignis): Plate LX (c. 1575/80), Joris Hoefnagel. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Similarly, the cheeses, associated at once with cosmogony and spontaneous generation, conceal a world at a scalar remove. In Micrographia (1665) – the first work to present images of insects and objects seen beneath the lens of a microscope – Robert Hooke calculated that ‘there may be no less then a million of well grown Mites contain’d in a cubick inch [of cheese], and five hundred times as many Eggs’. In Caterpillage (2011), a wonderful book of essays on Dutch still life, Harry Berger, Jr describes the stack in van Dijck’s painting as like ‘a solar system of its own’, each cheese rotating on its axis and drawing the other elements of the composition in as satellites. Though the cheese stacks depicted in the paintings of Peeters, van Dijck, and their contemporaries may have the apparent stillness of the monumental, they are sites of latent animation, liable to spontaneous generation, the potential habitat of millions.

The effect of this, and of van Huysum’s insects, on the viewer of these paintings – on this viewer, at least – is not to create a sense of imminent decay, but rather to attract the eye to attend to surface and complexity, to examine not separate objects but the worlds they make up in microcosm. It dissolves still further the independence of flower and fruit, making them a sequence of variegated textures. To be the fly at van Huysum’s feast means to attend to the upholstery of the peach; to be the ant is to negotiate the crepe-like tissue of the carnations, to sink in the succulence of the deliquescing plum. In the schists and schisms of Peeters’ cheese, passages of apparently realist paint become landscapes of potential vitality. The still lifes offer up a fractal world, revealing the strangeness and complexity lurking in the familiar. Even the slowest of these food paintings depicts a life that is anything but still.

From the March 2017 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

‘Slow Food: Still Lifes of the Golden Age’ is at the Mauritshuis, The Hague, from 9 March–25 June.