In 1997, a pair of clinical therapists called Judith Wyatt and Chauncey Hare (1934–2019) published a book called Work Abuse and How to Survive It. The preface ends with the authors’ biographies, in which Hare describes himself as the recipient of ‘six major grants, including three Guggenheim fellowships’ and that, before becoming a therapist, he had ‘a variety of jobs in the private and public sectors’. But nowhere does he mention that he had received great acclaim as a photographer in a career that invited comparisons to Walker Evans and Diane Arbus. Hare, who once called himself an ‘anti-official art artist’, had a solo show of his work at MoMA in 1977 and published two well-received monographs. Work Abuse does, however, contain a checklist in which Hare might be advising his former self: ‘Become aware of and accept your own anger, frustration, and resentment, so it doesn’t leak out toward your boss. If you can’t stop power struggling, become aware of any concealed wish to self-destruct.’

Robert Slifkin’s engaging critical biography of Hare is the first of this contrarian figure. The title is ironic: Hare never fully succeeded in quitting a day job. Throughout his most creative period, from the 1960s to the beginning of the ’80s, he worked as a chemical engineer at Standard Oil California (SOCAL), taking year-long breaks courtesy of grants. After leaving SOCAL, in 1977, citing the suppression of his (authorised) documentation of working conditions, he went to art school to get an MFA, despite being more successful than any of his teachers: the MoMA show opened that autumn and he had already had small shows at the De Young Museum and the San Francisco Museum of Art earlier in the decade. He severed his relations with formerly supportive art institutions, accusing them of ignoring his newly politicised photography. Failing to get teaching work, he became a home help to a former SOCAL employee, worked at the non-profit Environmental Protection Agency and then retrained as a therapist specialising in ‘work abuse’.

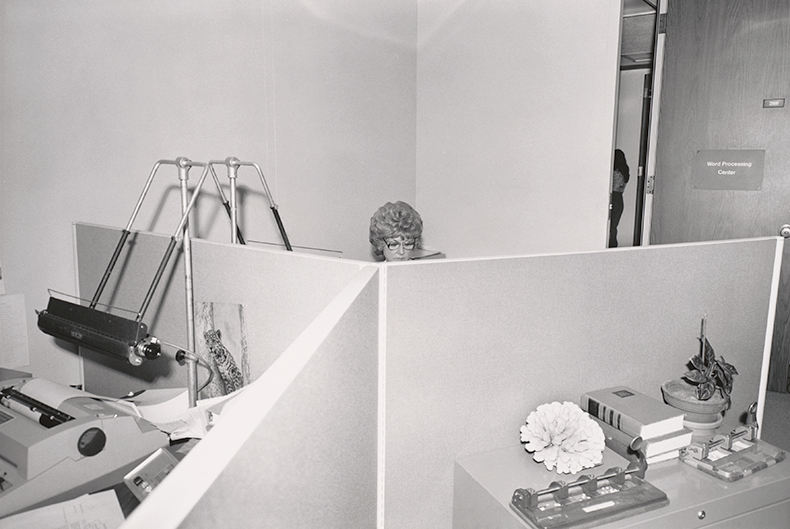

Head of female worker seen over office cubical, Standard Oil Company of California (1976–77), Chauncey Hare. From Quitting Your Day Job: Chauncey Hare’s Photographic Work by Robert Slifkin (MACK 2022). Chauncey Hare Photograph Archive. © The Regents of the University of California, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley. This photograph was made by Chauncey Hare to protest and warn against the growing domination of working people by multi-national corporations and their elite owners and managers.

Slifkin argues that rather than seeing Hare’s work and art in conflict, or necessary foils for each other, we should understand his many swerves as part of the same process. Work and how corporate environments were shaping the American psyche and domestic life was Hare’s main photographic subject. The growing need to ‘agitate’ in his day job consumed him to the point he could see the same institutional strictures and repression of dissent everywhere, even in the art world that had first represented an escape. The strongest case that Slifkin makes in his timely book, however, is for the continuing power of Hare’s bleak and strange images.

Interior America (1978) and This Was Corporate America (1984), which collect work made from the 1960s onwards, move from the home to the outside world. The families and individuals in Interior America seem cornered in their own houses by trailing telephone cords and pen-like arrangements of furniture. The skewed perspectives and the careful placement of family photographs and reproductions of art in the interiors of the new middle-class seem to presage the personalised cubicles of the later volume.

There is an evident kinship with Arbus in the seedy, stark interior shots. In contrast to Arbus’s often confrontational treatment of her subjects, however, Hare’s seem exhausted or resigned. This is most notable in his portrait of 1968 of Orville England, an injured Standard Oil worker. He is the subject of Hare’s first published interior shot, a move away from photographing landscapes and Hare’s earliest instance of trying to document his theory of work abuse, consisting of, as Slifkin puts it, ‘the treacherous imbrication of work and home’.

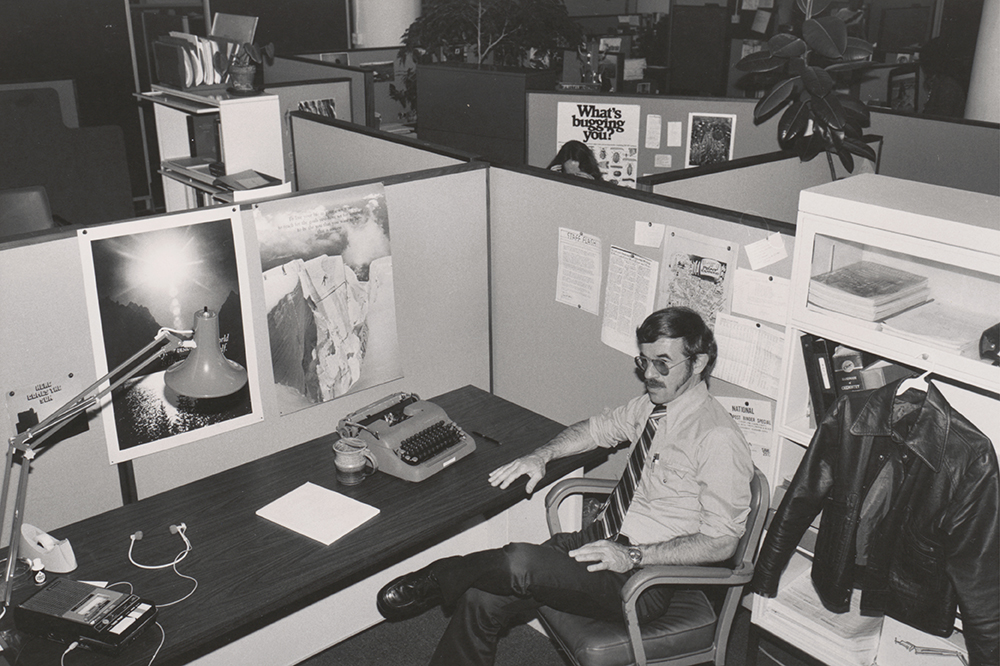

The offices in This Was Corporate America include those of the Social Security Administration and Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Workers are often blurred in motion or obscured by towering boxes and carts. In one picture, one employee looks up at a sad helium balloon of a teddy bear in a T-shirt bearing the slogan ‘HUG ME’ hovering just out of reach above her desk. A self-portrait at the EPA is especially powerful. Perhaps talking to someone outside the frame, Hare stretches his legs out, coat hanging next to him, the few items on his desk resembling props. Here Slifkin notes a similarity with Cindy Sherman’s adoption of disguises and creation of fictional scenarios, in that Hare saw ‘self-presentation as a matter of performance’. Conversely, Hare’s role-playing also seems to suggest the psychic inescapability of his day job.

Hare needed the approval of an institution to feel that he could rail against it. Slifkin argues that he ‘sought to free himself from the weight of one patriarchal, authoritarian, and oftentimes abbreviated entity, only to exchange it with another legitimising authority’. Hare’s fixation on an accompanying book was driven by his odd belief that the book would resolve his self-diagnosed ‘credibility problem’ with SOCAL management and force them to improve working conditions.

Hare’s instrumental approach to the art world was also a product of his growing disillusionment with its structures. In This was Corporate America, he writes that MoMA’s offices were similar to those at SOCAL and that the curators shared an ‘authoritarian outlook’ with corporate management. After the show opened, Hare was so disappointed with the failure of the wall captions to foreground the political intent of the photographs that he called on John Szarkowski to change them, besieging the curator with correspondence that included a taped missive featuring musical interludes.

Slifkin acknowledges the paranoid and self-sabotaging nature of Hare’s actions, while remaining sympathetic to his questioning of the art world’s corporatisation. Hare later picketed a travelling MOMA exhibition decrying Szarkowski’s inclusion of an older photograph at the expense of the new work and the show’s sponsorship by Philip Morris. He sent graffitied, torn catalogues of the exhibition directly to MOMA trustees, accusing them of covering up for his old employer.

Richmond, California (n.d.), Chauncey Hare. From Quitting Your Day Job: Chauncey Hare’s Photographic Work by Robert Slifkin (MACK 2022). Chauncey Hare Photographic Archive. © The Regents of the University of California, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley. This photograph was made by Chauncey Hare to protest and warn against the growing domination of working peo- ple by multi-national corporations and their elite owners and managers.

By paying more attention to some periods of Hare’s life than others, Slifkin’s account of Hare’s artistic journey is more selective than he first intimates. Hare’s time as a home help for Orville England – closing the early ironic distance from his subjects – is skimmed over. There is no mention of what happened to Hare’s first wife and son, who figure in the early, domestic, photography , and Slifkin tells us of Hare’s complicated relationship with his father, an amateur photographer and corporate man, very belatedly. Hare’s work as a psychotherapist – and dubious use of his own thinly disguised experiences as clinical evidence – also remains unexplored.

Whatever Hare’s motivations for taking photographs and then stopping taking them, his cold-eyed view of office life seems more truthful than ever. While Hare remains a uniquely driven figure, rooted in his own time, his concerns – the encroachment of work on home life and the value ascribed to what kind of work we do – are, worryingly, still ours.

Quitting Your Day Job: Chauncey Hare’s Photographic Work by Robert Slifkin is published by MACK