Charlotte Salomon’s extraordinary Leben? oder Theater? (Life? or Theatre?), a series of more than 700 colour gouaches on sheets of paper, is an early graphic novel of sorts. It portrays her terrifying family history of mental illness, likely incest and suicide through images, directions for music and words transcribed on transparent overlays that sit on top of the paintings. Salomon herself described the work as a singspiel – a piece of musical theatre. The characters – most of whom are family members who re-enact dark scenes from their collective past – are listed at the start of the series, as in a theatre programme. Graphic novel or musical play, it’s a totally unique work of art, produced in extreme circumstances.

Born in Berlin in 1917, Salomon created Leben? oder Theater? between 1941 and 1942 when, as a German Jew, she fled Nazi Germany for the south of France with her grandparents. It was while they were in hiding in the villa of the rich American Ottilie Moore that Salomon’s abusive grandfather (he liked to share a bed with Charlotte if he could manage it, and it’s likely that he preyed on other women in the family) chose to reveal her complicated family inheritance, explaining that seven of her relatives had killed themselves. The series was her defiant response: ‘I will live for them all’ she wrote. And if she didn’t paint, she was sure she would lose her mind. Salomon wrote on one of the last pages: ‘She found herself facing the question of whether to commit suicide or to undertake something wildly extraordinary.’ She chose the latter, and retreated to a nearby hotel to paint, where the young German would sit and hum to herself as she worked. She seems to have made the series in a sort of frenzy; there are so many paintings, all done in such a short space of time.

No. 22 from Leben? oder Theater? (1941–42), Charlotte Salomon. Jewish Historical Museum, Amsterdam. © Charlotte Salomon Foundation, Charlotte Salomon ®

Salomon was living in uncertain, dangerous times, and had an acute sense of the proximity of death, but she wanted her paintings to endure. In February 1943, she wrapped the series in brown paper, giving it to a friend, the doctor Georges Moridis. She begged him to ‘take good care of it, it is my entire life’. Leben? oder Theater? speaks powerfully of a woman making art in the face of breakdown, family tragedy, war and national crisis. Jacqueline Rose has written eloquently about Salomon and the difficult contexts of her work in Women in Dark Times (2014). In darkness sometimes there’s a crack that lets the light get in. The work on show here – there are more than 200 small gouaches on display at the Jewish Museum – was Salomon’s light. The paint colours are intense and vivid, a mixture of blues, reds and yellows; bright flashes in the dark she found herself inhabiting. Colour can mean freedom here. In a key painting, an open window of blue sky beckons both the painter and the viewer; the space beyond the window is enticing, empty, clean. Her mother jumped out of one, killing herself when Salomon was eight years old. ‘The empty window’ (the description used by the curator), with its room of aquamarine walls, blue floorboards and open window, has an overlay with the words: ‘Now she no longer stands there. Ah me, in a different place, she now abides.’

Elsewhere, there are crumpled bodies after jumping out of other windows. Salomon’s grandmother also committed suicide by throwing herself out of one, and this event is imagined by the artist. ‘Preparing to jump’ shows a series of women lying on beds in a room with a floor that resembles a field of flowers. At the edge of it – seen through an abstracted window opening at the edge of the work – sits a free-floating blue-framed window with a small figure (the mother character) standing on the sill, poised to let herself go. The overlay for this painting reads: ‘The nurse shares this opinion. However, she confuses hope for the future with the reality of the present, and for one moment – which is utilized by Franziska to throw herself out of the window – leaves the room. Franziska: “I cannot bear it any longer. I am always so alone.”’ It is family autobiography in all its stark grimness, done in words and images. In another gouache, further along, there’s the body on the floor. Like many of the figures in the series, it is edged in dark brown paint to separate it off from the bright background. One arm is on top of her head, a leg awkwardly extended at an unnatural angle, her pale pink nightdress rucked up. She is lying on what looks to be grass, done in yellows, greens and blues with small dabs of the brush. It is quite Van Gogh-like.

No. 134 from Leben? oder Theater? (1941–42), Charlotte Salomon. Jewish Historical Museum, Amsterdam. © Charlotte Salomon Foundation, Charlotte Salomon ®

Salomon wrote of her series: ‘I became my mother, my grandmother […] I was all the characters who take part in my play. I learned to travel all their paths and became all of them.’ There is an intimacy to the reimagining here, an attempt to embody these women, to get inside their heads. It’s a brave thing to do, especially given the mental anguish they experienced.

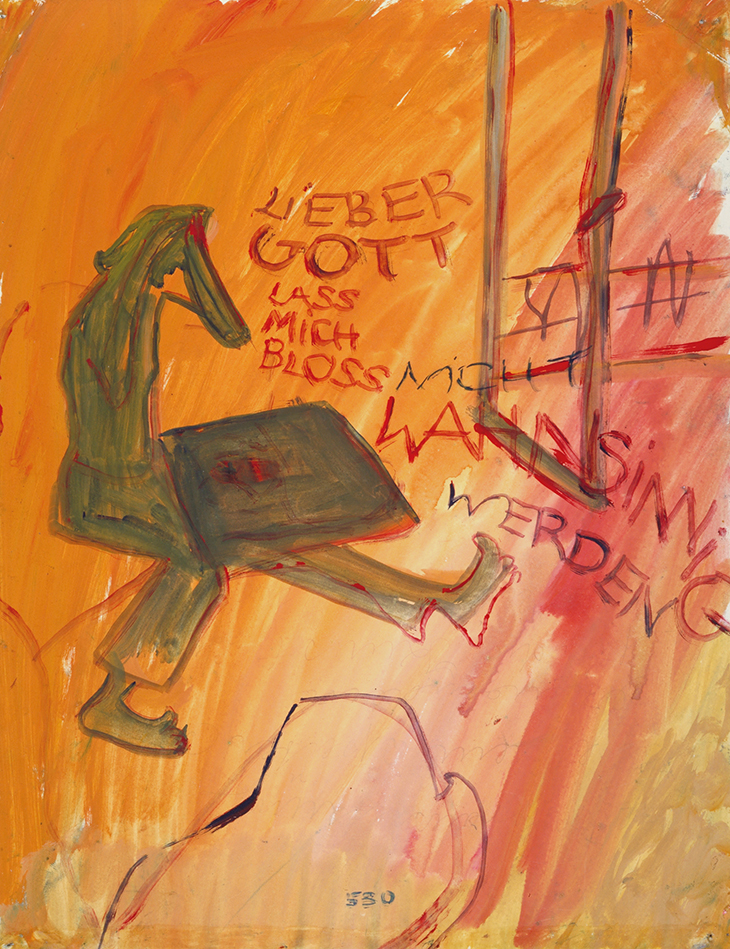

Salomon seems to have had a constant fear of going mad herself. One painting with an orange and red painted background features a figure done in rough dark brown brushstrokes, holding a book and clutching her head, one leg awkwardly extended in front of her. She looks despairing. The accompanying text, painted in red and dark brown paint in childish capitals on top of the fiery orange, reads: ‘Dear God, only please don’t let me go mad.’ It is a terrifying cry from the heart, but Salomon had a grit and a determination that kept her going, kept her painting. It’s possible that she also found a way to triumph over her abusive grandfather, who died from barbiturates hidden inside an omelette. Recently discovered pages written by her suggest she may have killed him.

Leben? oder Theater? is a complicated work to experience on the exhibition walls; there are so many words to read, so many directions to take in. The paintings are intricate, detailed, require up-close investigation. The gouaches at the start of the show seem to be done more carefully than others; a roughness, a carefreeness creeps in as things get going. There are shades of Dufy, but many of the female figures with their soulful faces and dark outlines resemble the creations of Paula Modersohn-Becker, another German woman painter who died too young (in 1907, at the age of 31, from an embolism after giving birth). Like Modersohn-Becker and so many of her family members before her, Salomon died prematurely, at the age of 26. She was killed by the Nazis in Auschwitz on 10 October 1943. She was five months pregnant. In Leben? oder Theater? it’s extraordinary to see what she made out of such darkness.

No. 530 from Leben? oder Theater? (1941–42), Charlotte Salomon. Jewish Historical Museum, Amsterdam. © Charlotte Salomon Foundation, Charlotte Salomon ®

‘Charlotte Salomon: Life? or Theatre?’ is at the Jewish Museum, London, until 1 March.

From the February 2020 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.