‘A man of Byzantium who came to Venice by way of Greece,’ reads the epitaph on Carlo Scarpa’s tomb, inscribed at the architect’s own request. Scarpa was born in Venice and lived there for most of his life but drew influence from a wide range of sources including the work of Frank Lloyd Wright. Like Lloyd Wright, Scarpa never formally completed his architectural studies, but this did not prevent him from teaching in the architecture faculty at the Università Iuav di Venezia nor from winning numerous architectural commissions throughout the city, some of which were completed posthumously by his followers.

Japanese design was also important to Scarpa; several of his major projects feature motifs such as straight lines, paths and pools of water. The gaps and slippage in the materials count as much as the solid in his designs – water, what Venice is built upon, was of particular interest to the architect. In 1961 he wrote how ‘wonderful’ working with water was: ‘holding it, controlling it, using it as a bright and reflective material.’

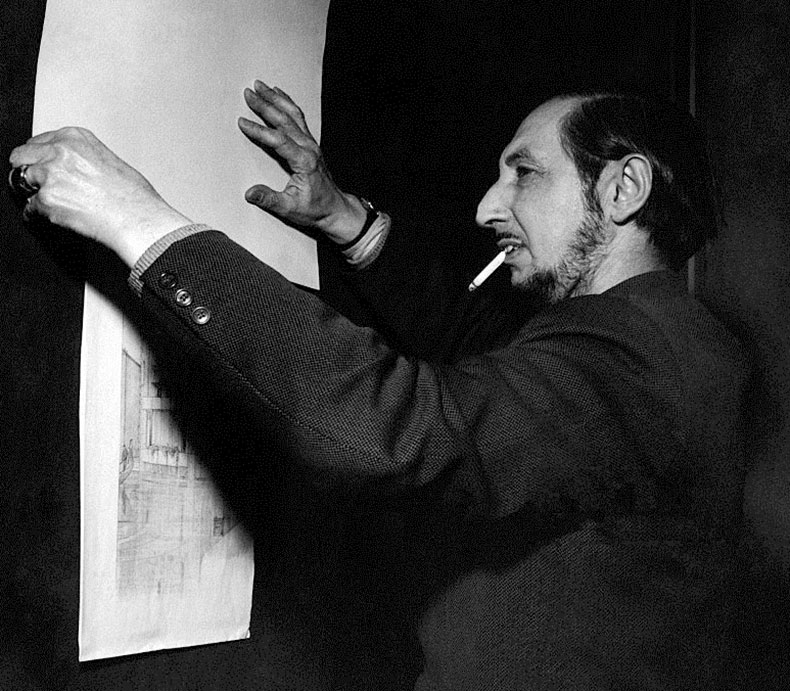

Carlo Scarpa studying the drawings of Frank Lloyd Wright, March 1954. Photo: Public domain (wikimedia commons)

Whether Scarpa was working with water, the expressive potential of concrete or the luminosity of glass (he served as artistic director of Venini glass in Murano from 1932–46), his designs initiated a dialogue between ancient and modern. He combined traditional building materials and methods from the Veneto into the composites of his refurbishments, while each detail of his work – a joined teak corner, a brass railing, an Istrian stone cover – contains a history of architectural innovation.

Until recently, Scarpa’s interventions have gone relatively unnoticed by visitors to Venice in favour of the many grand gothic palazzos. Yet, his work is an important part of the fabric of the city’s history. By studying, planning, cutting, re-joining and expanding the materials of existing buildings, Scarpa teased out past structures and revealed their modernist potential. As the city prepares to open the 18th edition of the Biennale Architettura on 20 May, these six Scarpa buildings offer a meditation on the architecture of Venice that should not be missed.

The Aula Mario Baratto in Ca’Foscari University, Venice. Photo: courtesy Ca’Foscari University

Aula Mario Baratto in the Ca’Foscari University

Aula Mario Baratto, or the Barter’s Hall, was developed by Scarpa between 1935–37 and then again between 1955–56 when the space was transformed into a lecture hall. The view over the Grand Canal is enhanced by Scarpa’s interpretation of the Gothic polifora – the traditional Venetian windows – for which the architect created a modern wooden frame with diagonal shapes.

The sculpture garden in the Italian Pavilion. Photo: Eugenio Pingo/Alamy Stock Photo

The Italian Pavilion at the Biennale Giardini

In 1948, Scarpa was commissioned to begin renovations of the main biennale building, the Italian Pavilion. The project spanned several years and involved many different stages, including a redesign of the adjacent Book Pavilion. In 1968, Scarpa raised the central hall of the pavilion to a loft, doubling the exhibition area. He also remodelled the Sculpture Garden, building pillars to hold a canopy structure (also seen in the ticket booth designed by Scarpa outside the Giardini) of three different arc shaped roofs, that are constructed to come close enough to the walls without touching them, to capture light. He additionally added four pools, bearing a spout that shoots water on to a copper disc to create a meditative chiming sound.

The mezzanine level of the Olivetti showroom on Piazza San Marco. Photo: claudia beretta/Alamy Stock Photo

The Olivetti showroom

In 1957, Adriano Olivetti asked the architect to design a space to display his brand’s typewriters in the arcades of Piazza San Marco. The small space is only 21 metres deep by five wide and four metres high with irregular-shaped, brightly coloured tesserae on the floor and a marble staircase that leads up to a mezzanine where visitors can wander the narrow pathways, admiring the typewriters displayed on rosewood shelves, and peek out of windows across the square.

The garden at Fondazione Querini Stampalia. Photo: Arcaid Images/Alamy Stock Photo

Fondazione Querini Stampalia

The palazzo was remodelled by Scarpa over 10 years, beginning in 1949, under the forward-looking vision of the foundation’s director, Giuseppe Mazzariol who was a great admirer of the architect’s work. The building is sealed off by the canal, and visitors must cross over the metal and teak bridge resting on Istrian stone – the lightest in Venice – to gain entry. Scarpa’s designs sought to blend the old and new by carefully renovating the existing architecture and focusing on the craftsmanship of materials. No detail was too small to attend to – even the radiator covers are Istrian stone with pure gold bands. The inevitable overflow or acque alte from the canal is also aesthetically dealt with; the water seeps on to the ground floor and is channelled through alabaster labyrinths.

Palazzina Masieri

Palazzina Masieri was intended to be the private residence of the architect Angelo Masieri, who wanted to commission Frank Lloyd Wright to renovate the interiors. However, Masieri was killed in a car accident before the project came into fruition and the family instead asked the American architect to transform the building into a residence for promising students at the IUAV (Istituto Universitario di Architettura di Venezia) in Masieri’s memory. Lloyd Wright’s proposal was rejected by the Venetian Municipality in 1955 who considered the design to be too extreme.

Scarpa came on to the project in 1968 (it was completed posthumously in 1983) to rework the interiors while preserving the historic facade. Part of his proposal involved the reconstruction of an ancient second chimney, which the city authorities initially rejected. However, Scarpa found drawings by Canaletto of the same building from three centuries before, which showed two chimneys in the original design and won the argument. ‘Buildings that imitate look like impostors, and that is just what they are. No one is fooled,’ he stated in a letter complaining about the conservatism of Venice’s building authorities.

The vesica piscis at Tomba Brion in Treviso. Photo: Alessandra Pezzotta/Alamy Stock Photo

Tomba Brion

One hour from Venice, in the cemetery of San Vito in Treviso, lies the recently restored Brion Tomb. The tomb was commissioned in 1969 by Onorina Tomasi Brion, widow of Giuseppe Brion, the founder of the electronics company Brionvega, to commemorate her husband and become her eventual resting place. The project became a kind of architectural manifesto for Scarpa who loved it so much, he asked to be buried there. At the centre of the tomb there is a sculpture of two intersecting circles (the vesica piscis, a recurring feature in Scarpa’s work) symbolising ying and yang, or the male and female merging into one. Scarpa’s interest in Japanese architecture can be seen in the adjoining meditation pavilion which is surrounded by pools filled with water lilies.