The National Gallery of Canada’s exhibition ‘Canada and Impressionism’, which opened last week at the Kunsthalle München, begins with a pair of projections. Visitors are presented with an antechamber of archival footage: on the left, Paris at the turn of the 20th century; on the right, Canada at the same moment. Flâneurs and commuters are juxtaposed with the building of the Canadian National Railway. Boys in short trousers sail model ships in a fountain on one wall, and on the other timber is dumped from a railcar into the water. This counterpoint of European urbanity and polish with Canadian wildness evokes a conceptual distance between ‘Canada’ and ‘Impressionism’. Yet in evoking this distance, the curators also hint at the productive pressure these two terms might exert on one another. Visitors to this exhibition in Munich, or on its later stops in Lausanne, Montpellier, and finally Ottawa, are invited to consider the now largely forgotten influence of French Impressionism on the development of Canadian art. But this exhibition’s more ambitious goal is to make a case for the entanglement of the Canadian periphery with the artistic centres of Europe, and to suggest the ways in which Impressionism was reshaped by Canadian artists and in response to Canadian subjects.

Snow II (1915), Lawren S. Harris. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. © Family of Lawren S. Harris

The exhibition is arranged chronologically across the period 1880 to 1930. It begins with a group of artists who arrived in Paris to study, to exhibit, and to absorb the atmosphere at the French academies, and finishes with the Group of Seven – Canada’s famed ‘Algonquin School’ of landscape painters active in the 1920s and ’30s – and Emily Carr. The reinstatement of this historical narrative is especially valuable because many of the 35 artists from across Canada who are on show are now relatively unknown. Some, such as Henri Beau and James Wilson Morrice, stayed more or less permanently in Paris; some (Helen McNicoll and Dorothea Sharp among others) formed their own studios there; others, including Maurice Cullen, returned to Canada. The exhibition makes it possible not only to develop a new sense of Canadian Impressionism as an artistic movement – one that complements the recent rise to prominence of other regional impressionisms – but also to trace the shifts in a single artist’s style over time. The chance to compare Cullen’s Paris, Winter on the Seine (1902) and Lifting Fog, St. John’s, Newfoundland (c. 1913) bears out, for instance, the curator Katerina Atanassova’s claims that the particular demands of Canadian landscapes and Canadian light necessitated stylistic adjustment. While both are winter scenes, the warmth and clarity of the first painting give way to a colder, paler palette in the second picture, in which flimsy houses and docks are set along a coastline that seems barely able to resist dissolving into mist.

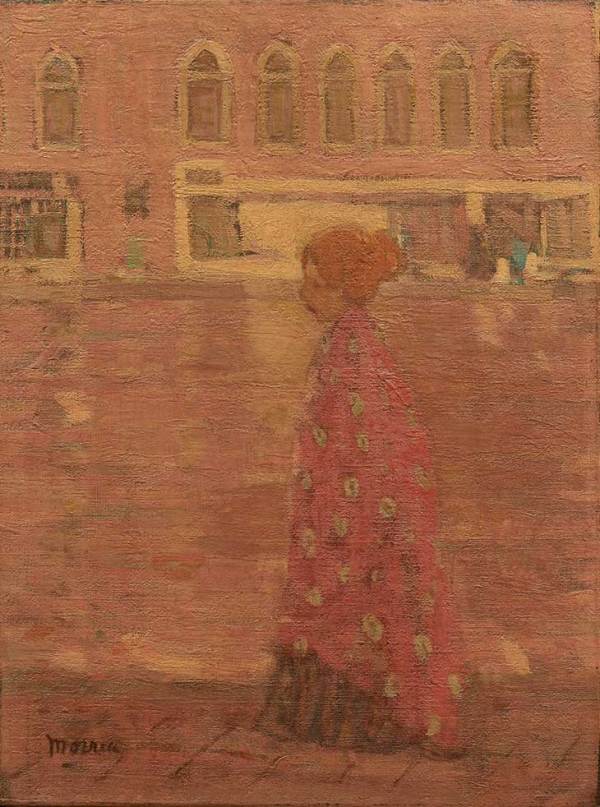

Venetian Girl (c. 1902), James Wilson Morrice. Photo: National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

Arising out of a desire to emulate French Impressionists, and beginning at a time when, as Atanassova put it in the exhibition catalogue, ‘this painting style had already gone out of fashion in France’, Canadian Impressionism was belated: a by-product or an offshoot of Impressionism proper. The mistimings and misapplications of Canadian Impressionism take, however, positive forms as well as negative ones, as in the example of Morrice, one of the most prominently featured artists here. A friend of Henri Harpignies and Henri Matisse, as well as a juror at the 1908 Salon d’Automne with Matisse, Albert Marquet, and Georges Rouault, Morrice became perhaps the Canadian artist most firmly integrated into Paris society. However, the thinly painted, blocky planes of colour of his urban and society scenes – see The Blue Umbrella (c. 1898) or the stunning Venetian Girl (c. 1902) – are more reminiscent of Whistler or Bonnard than Monet or Renoir. This muddling of the narrative, noted by Adam Gopnik in his catalogue essay, of Canadian Impressionism ‘as a false step before the Group of Seven took the fully national leap forward’ is welcome – a disturbance of the implicit teleology of many chronologically organised exhibitions.

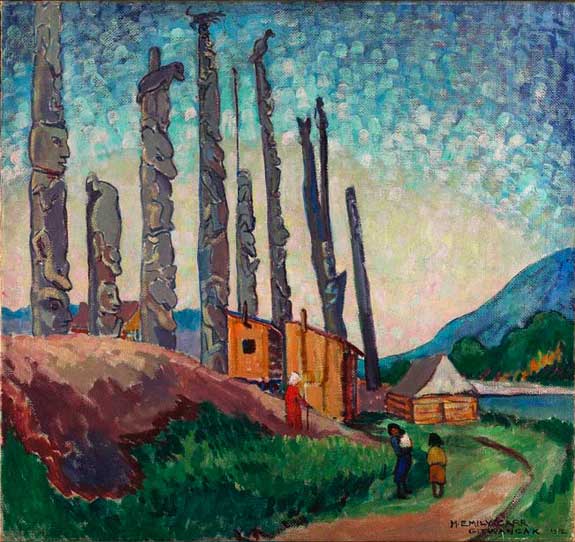

Gitwangak (1912), Emily Carr. Photo: © Art Gallery of Ontario

Nevertheless, the version of Canadian art that most occupies the exhibition has to do with the landscape, the weather, and what Gopnik calls ‘the great plaintive Canadian intuitions of loneliness and survival’. It is true that the Group of Seven were particularly invested in this version of Canadian identity: a looped clip from a historic documentary of A.Y. Jackson shows the artist painting in snowshoes and travelling in a canoe, and informs viewers that Canadian artists ‘must be able to wield a paddle as well as a brush’. And it remains wonderful to see works in this vein: David B. Milne’s vivid post-Impressionist The Blossom Pickers (c. 1911/12) is still startling, for example. Meanwhile, Carr’s Gitwangak (1912), familiar as its representation of totem poles in the titular village in northwestern British Columbia will be to most Canadian visitors, is particularly welcome as the only picture in the exhibition to demonstrate that art existed in Canada before Europeans arrived. Indeed, the absence here not only of works by First Nations artists but of any discussion of their presence and influence is a reminder of the colonial elision of indigenous experiences – an elision that can also take place when familiar platitudes about the Canadian landscape and its effect on Canadian art and identity are invoked. More could have been done here to unpack the racial and colonial dimensions of these artists’ concepts of landscape and identity, to contextualise and deflate them, in addition to scrutinising the at-once nostalgic and exotic appeal their paintings make to European viewers.

For these reasons, I was more attracted to the moments in this exhibition when claims for the possibility of a specifically national art fade from view. While paintings such as Morrice’s The Terrace, Quebec (1910/11) or L.L. Fitzgerald’s Summer Afternoon, the Prairie (1921) announce their relationships to particular locations, they could really be images of anywhere. They are available to Canadian identification and recognition, but not limited to it. One of the things most amply demonstrated by this exhibition, then, is Impressionism’s flexibility as a style: its transportability, and amenability to repurposing. If Canadians came to Europe partly in search of the legitimacy and prestige a quintessentially Parisian style might confer, they may instead have demonstrated the ease with which any style might be prised from its national origins and transplanted.

‘Canada and Impressionism: New Horizons’ is at the Kunsthalle München until 17 November. It then travels to the Fondation de l’Hermitage, Lausanne (January 2020–May 2020) and Musée Fabre, Montpellier (June 2020–September 2020).