The Istanbul Biennial has long used the city’s wealth of beautiful and usually off-limits historic buildings as its settings. This year some of the most remarkable venues are again on the Princes’ Islands, whose grand, decaying fin-de-siècle mansions once hosted the leading families of Istanbul’s Greek, Armenian and Jewish elite. Today, after a century of pressure and persecution, many of these families have left, and their houses, often taken over by the state, stand empty.

Building on this traumatic history, the biennial has now created a fun and slightly spooky haunted house tour complete with contemporary art. My just-a-bit-jarring journey begins on the forested peak of Heybeliada (Turkish) or Halki (Greek), a few miles southeast of downtown Istanbul in the Sea of Marmara. Here, an Orthodox theological school that once trained priests for the Ecumenical Patriarchate stands closed since 1971. Coinciding with the biennial, on the day of my visit an exhibition put on by a local diving society offers a rare chance to see inside a building that remains the subject of a high-profile Turkish-Greek diplomatic dispute (closed 22 September).

In one unused classroom, gilt metallic replicas of small ribcages sit atop rows of children’s desks, while several more spinal columns dangle from the ceiling (Hera Büyüktaşcıyan’s Kılçık III ve IV [Fishbone III and IV; 2015]). In another classroom, a network of tubes connect jars of coral to a central tank, pump and refrigeration unit (Sibel Horada’s Göç Dalgası [Migrant Wave; 2019]). The coral was supposed to be alive, but it has died and turned black. The water continues to circulate through the jars of dead coral, making the whole contraption appear more sinister than intended.

Installation view of Hale Tenger’s Suret, Zuhur, Tezahür (Appearance; 2019) at the Istanbul Biennial, 2019. Photo: David Levene. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Nev Istanbul

The nearby Büyükada (or Prinkipo) serves as one of the three sites of the biennial itself. Here, the stately stone mansion of the former Patriarch of Alexandria, subsequently used as a primary school by the Turkish Republic, lies completely in ruins. In the garden, visitors stare at their darkened reflections in the black obsidian mirrors of Hale Tenger’s Suret, Zuhur, Tezahür (Appearance; 2019). From above, a breathy voice reads out a poem from the perspective of a tortured tree, with scarred bark and iron pegs in its trunk: ‘They shamelessly pick my ripened fruit […] I cannot go anywhere. Nor do I want to.’

Closer to the water, the mansion of Con Hacopulos has been converted into a civil administrative building, supposedly still in use despite its ramshackle appearance. On the columned porch, Monster Chetwynd’s half-human half-animal hybrids pose for pictures with visitors in their cloth and wire glory. Behind a 10-foot-tall batwoman, a panel explains that the artist’s ‘signature aesthetic’ is one in which ‘sexuality, the grotesque, the humorous and the spooky all vie for attention’.

View of Büyükada. Photo: Sahir Uğur Eren

For this visitor, at least, it was all the vying that proved disconcerting. The art not only vies for attention with the buildings, but also with the weight of their history. The problem isn’t that the venues risk overwhelming the works; rather, they put an unfair burden on them. There is no reason art in Istanbul should have to wrestle with, or even acknowledge, the fate of the city’s religious minorities – unless, of course, it is displayed in buildings that so powerfully symbolise that history. These venues seem to demand that the art reckon with how it has ended up being displayed in them. And the artists don’t seem entirely sure how to respond. Are they commenting on the haunted setting, or just making use of it?

In search of an answer, I ask Aslı Çavuşoğlu, an Istanbul artist who lives on the island and has previously exhibited at the biennial. She tells me she thought there was something fitting in ‘the idea of a courthouse becoming a ghost house’. How intentional was it though? ‘That’s the point – even as a professional, I’m not sure.’

Installation view of Armin Linke’s Prospecting Oceans (2018) at the Istanbul Biennial, 2019. Photo: Sahir Uğur Eren. Courtesy the artist

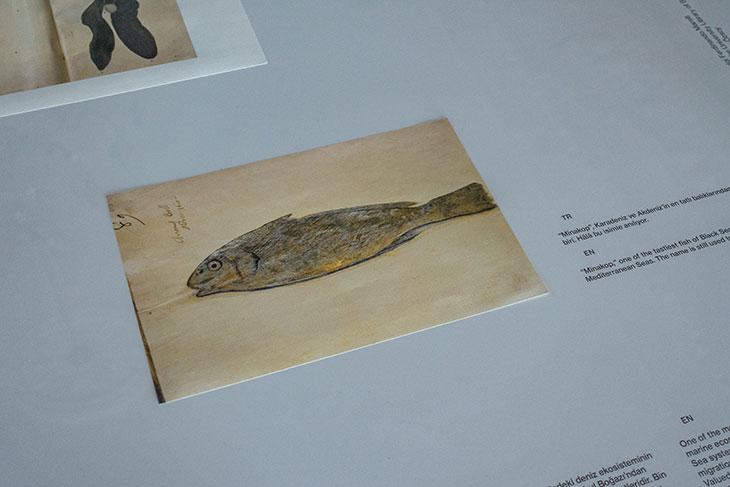

Back toward the ferry dock, the island’s still-very-active yacht club plays host to Armin Linke’s Prospecting Ocean (2018), a series of installations dealing with the region’s lost maritime heritage. The native Nicomedian lobster, visitors learn, ‘became extinct in the 1970s’ and was ‘locally originally called “istakoz” (Greek)’. Next door, a Greek-themed fish restaurant plays taverna music and sells lobster by the kilogram under the distinctly non-Greek name ‘sea beetle’. Undoubtedly there’s a bigger point to be made here about dispossession and loss. No one could quite ignore it. But it’s unclear, on this sunny autumn day, if anyone really wants to make it either.

‘The Seventh Continent’, the 16th Istanbul Biennial, runs until 10 November.