Béla Lajta is a name little known outside Budapest and, frankly, one not that well known there either. While other figures from the fin de siècle – Gaudí, Mackintosh, Loos, Wagner, Hoffmann – have been beatified and transformed into tourist icons, Lajta (1873–1920) languishes as a central European curiosity. Yet this architect was, without doubt, one of the most innovative and brilliant figures of an era overloaded with genius.

Take his Rózsavölgyi House of 1911–12. An exact contemporary of Adolf Loos’s Goldman & Salatsch Building in Vienna – which ruffled Viennese feathers with its unadorned severity – Lajta’s shop-cum-apartment block presents a perfect bridge between the stolid historicism of the 19th-century city and the stripped modernity of the 20th century. Or look at his Parisiana nightclub (later the New Theatre) of 1907–09, which seems to prefigure art deco and even postmodernism. Lajta’s work not only foreshadows the architecture which came in his wake but can also, perhaps, give us hints towards as yet unrealised forms and diversions.

To understand where this architecture came from we need to consider Budapest at the turn of the 20th century. Reams have been written about the role of the other capital of the Austro-Hungarian empire, Vienna, as the epicentre of modernity – a place where Freud, Schoenberg, Mahler, Musil, Klimt, and Kokoschka, among others, were busy building the world of contemporary culture. Far less has been said about a Budapest that produced Béla Bartók, Zoltán Kodály and Sándor Ferenczi, and was the city from which László Moholy-Nagy advanced into the Bauhaus.

In 1900 Budapest was the second-fastest growing city in the world (after Chicago). It was an industrial powerhouse and boasted a coffee-house culture that teemed with intellectual and literary debate. But it was also a city in search of an identity, new and insecure against the domineering presence of Vienna. When it built its parliament it looked to London, stealing the gothic style, adding a Brunelleschi dome and making the whole thing just a little bigger than the Palace of Westminster. In urban grain it looked to Paris and Berlin, cities of wide boulevards and heavily rusticated blocks with courtyards. But its architects were seeking something else that would make Budapest’s buildings distinctly Hungarian.

Following the English Arts and Crafts movement (Lajta worked briefly in Norman Shaw’s office in London) and in parallel with Finnish and Swedish National Romanticism, Hungarian architects looked to folk culture – as did those of so many other nations emerging from subjugation by more powerful neighbours. Lajta was much influenced by Ödön Lechner, the architect of eclectic, Eastern-influenced landmarks such Budapest’s ceramic-clad Museum of Applied Arts. His early works – similarly clad with ceramics – bear the marks of that enthusiasm, blended with the Byzantine, brick Romanticism of architects such as Eliel Saarinen, Hendrik Berlage, and even Louis Sullivan – but then they morphed into something else.

Lajta’s mausoleums in the Salgótarjáni Street Jewish Cemetery in Budapest are unlike anything anywhere. They seem to convey curious memories of ancient domes, temples and sculptures, as much Mesopotamian as Greek, a half-remembered melange of antique solidity and haunting archetypes. His black granite tomb for Emil Guttmann is an ominous dream, his Gries-family mausoleum a fragment of Solomon’s Temple, and his tomb for Lajos Schwarz, a massive, shadowy reinterpretation of Greek whiteness, its chunky sarcophagus sticking out from between stumpy columns like a swollen tongue. He invented three new architectural languages right here, in one cemetery, within a few months in 1907.

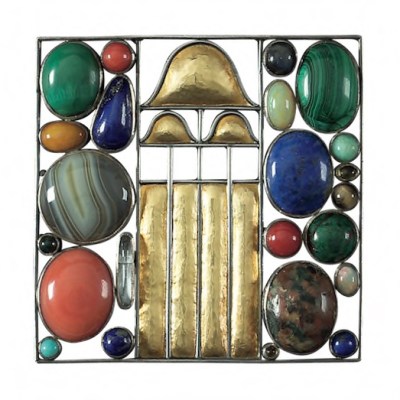

Like the families he was designing for, Lajta was Jewish (he Magyarised his name from Leitersdorfer in 1907). The population of Budapest was, in 1910, 23 per cent Jewish, and it highlights the very real integration of the Jewish community at the time that Lajta saw no obstacle to merging historic Hebrew motifs with those of the Hungarian peasantry. The shimmering golden mosaic interiors of the Gries mausoleum, for instance, are a cocktail of Hungarian, Hebrew, cosmological and antique patterns. This was a search for a national language capable of embracing all the individual identities of modern Budapest. Lajta collected folk art – everything from peasant hats to earthenware jars and horse collars, all richly inscribed with abstract decoration. He appropriated these patterns to produce bands of decoration, capitals for columns, and friezes giving relief to an otherwise severe architecture of almost geological mass.

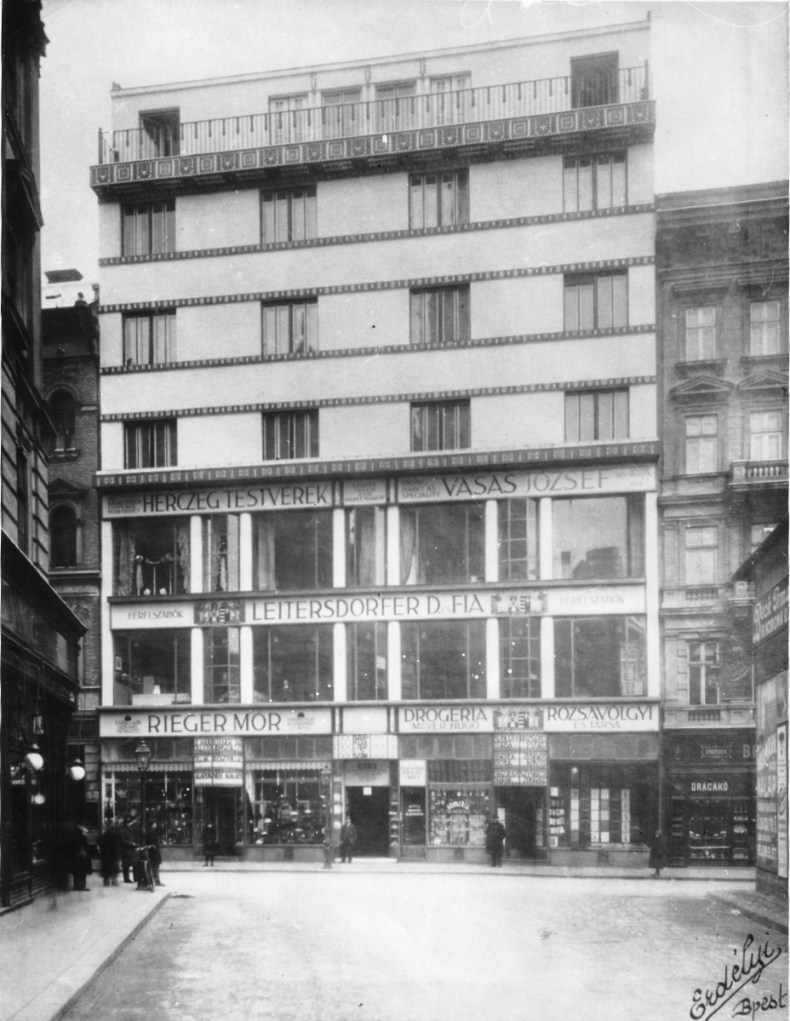

The Rózsavölgyi House, designed by Lajta and photographed shortly after its completion, in c. 1912. Courtesy Budapest City Archives

Lajta’s masterpiece, the Rózsavölgyi House, displays an utterly rational subdivision of retail, commercial, and residential space, expressed through the façade as purely as any modernist building of the 1930s. Between the stark white tiles, however, are slender bands of rich decoration in bronze, ceramic or copper, like layers of butter cream in a rich gateau. Those motifs appear too in Lajta’s trade school of 1910 on Vas Street, a massive brick extrusion with colossal columns looming over the narrow street. Its stairs are reminiscent of Adolf Loos’s villa interiors, its copper jardinières of the Wiener Werkstätte, and its massive, blocky entrances of some eerie Egyptian tomb. The building is book-ended by huge brick pylons and, in between, stepped brick pilasters prefigure the Hanseatic expressionism of Hamburg in the 1920s.

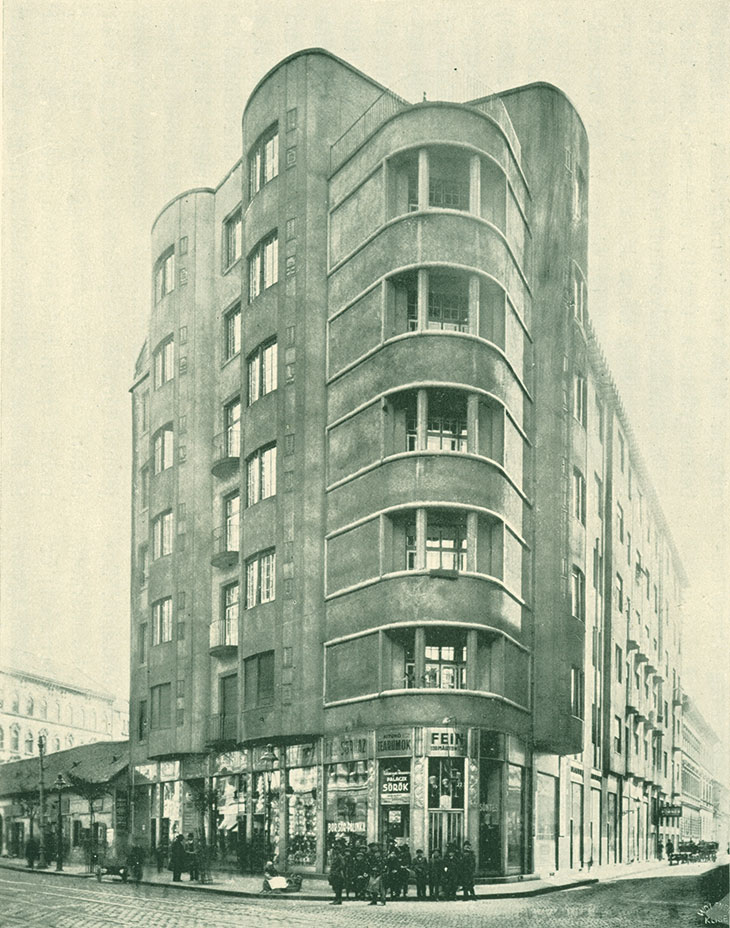

The Parisiana nightclub building in Budapest, designed by Béla Lajta (1873–1920) and completed in 1909 (reconstructed in 1991). Courtesy www.lajtaarchiv.hu

The proto-deco Parisiana nightclub is something else again. Its sheer façade of subtly veined white marble has openings inflected by Lajta’s studies of Assyrian architecture. The cleaning and restoration of the building in 1991 caused consternation – peeking out of a backstreet opposite the grand opera, it seemed to embody a theatrical kitsch. The flat façade looks like architectural greasepaint, its coloured highlights a garish affront to the grey city streets. Yet even here the stepped entrance doors echo ancient models and seem to refer to the Aztec forms that would so preoccupy American architects two decades later. But look up top: angels in the architecture. The frieze is an array of stylised angels, each holding a letter of the theatre’s name. There’s a hint of Otto Wagner here, but also a foreshadowing of Wim Wenders’ film Wings of Desire, the benevolent urban angels looking wistfully down on to life of the streets below.

Lajta’s apartment block on Népszínház Street, Budapest, constructed in 1911 (photo: 1913). Courtesy www.lajtaarchiv.hu

Each of Lajta’s buildings seems to foreshadow a little piece of the future – perhaps none more so than the apartment block he built on Népszínház Street in 1911. For many years pitifully dilapidated, its plaster peeling and its brick shell showing through (although some work seems to have started recently), the block curves around the tight corner with a streamlined sweep. It looks remarkably like the work that would emerge in Italy in the 1930s, a precedent of the rationalism which would become so influential. It suggests yet another new language of architecture.

Lajta had a short career and a relatively uneventful life. He was just 47 when he died in a Viennese sanatorium in 1920. But he left a body of work which is yet to be fully studied, which remains undeservedly obscure, and which still presents us with a myriad of possible architectural futures.

From the May 2018 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.