A young Tom Roberts attended a James Whistler exhibition held in London in 1884, and in the quickly produced, small-scale tonal paintings that he saw, he found the ‘tools’ with which to paint the changing landscape of his home, Australia. Inspired by Whistler’s example, Roberts and his contemporaries, Charles Conder and Arthur Streeton, began to paint the sensory experience of living and working in Australia in new and impressive ways.

Sandridge (c. 1888), Arthur Streeton. National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Impressionism in Australia flourished during a time of intense self-consciousness; as the Empire celebrated the centenary of English settlement in Australia, home to one of the largest and most urbanised cities in the world – ‘Marvellous Melbourne’ – Australians were also moving towards Federation, which they achieved in 1901. The two decades that the National Gallery’s exhibition ‘Australia’s Impressionists’ covers were ones in which artists were actively engaged in exploring ideas of nationhood.

Hoddle St., 10 p.m. (1889), Arthur Streeton. National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

An early highlight of the exhibition are the small-scale studies from the ‘9 By 5 Impression Exhibition’ held in Melbourne in 1889, and named after the dimensions of the works, many of which were painted on the lids of old cigar boxes. They explored the Australian landscape in all its diversity – from industrial harbour views to the gloomy metropolitan bustle of Hoddle Street. The exhibition seeks to readjust our perceptions of the Australian landscape by presenting its natural beauty alongside its modernity. Much like Whistler before them, these artists faced their own detractors: prominent art critic James Smith hurled his Ruskinesque criticism at the exhibition.

Golden Summer, Eaglemont (1889), Arthur Streeton. National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

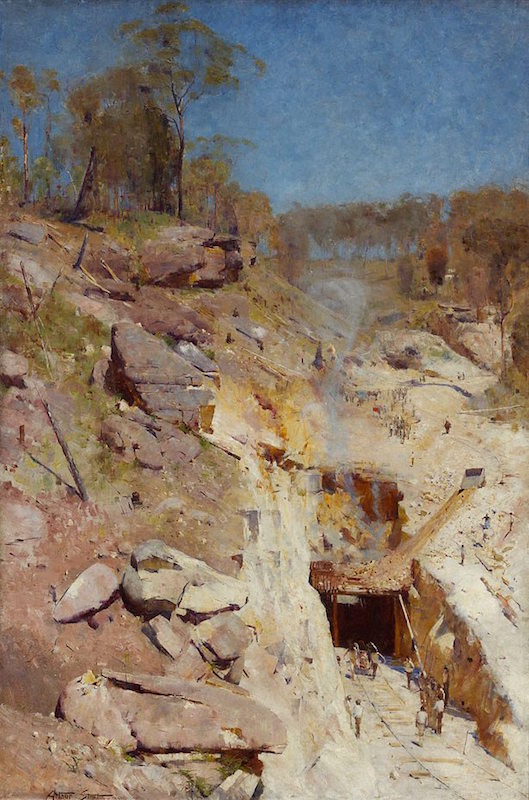

Nevertheless, Roberts, Streeton and Conder continued to develop a uniquely Australian vision of Impressionism. Roberts’ large-scale works range from lazy, rural idylls to the wilderness of the outback in A Break Away! (1891), in which man and beast are placed at the heart of the barren landscape. However, it is Streeton’s vast canvases that stand out, from the warmth and romance of Golden Summer, Eaglemont (1889), where crops appear as a bright mass of heavy brushstrokes, to the memorable Fire’s On (1891), in which an industrial tragedy is painted in an unusual vertical composition, en plein air (as all the artists in the exhibition preferred to work). Here, the small figures are engulfed by the imposing rocky valleys of the Antipodean landscape; the painting is a significant example of the ‘glare aesthetic’, developed to reproduce the sharpness of the Australian light in all its beauty and intensity.

Fire’s On (1891), Arthur Streeton. Art Gallery of New South Wales

The exhibition does propose interesting ideas of how Australian Impressionism deviated from its European counterpart. These artists projected a nationalistic view of Australia, exhibiting in Europe with a sense of pride and positive self-identity. While the exhibition might intend to readjust our perception of the Australian landscape, there are very few works that actually break away from mythic depictions of it – never more explicit than in the glaring white sands of a new Arcadia in Streeton’s Ariadne (1895). Furthermore, Roberts’ lyrical rural landscapes such as Winter Morning after Rain, Gardiner’s Creek (1885) don’t share the fleeting spontaneity that defines European Impressionism. As a result, it’s difficult to judge Australia’s iteration of the largely European style as simply the same thing in a different place.

Winter Morning after Rain, Gardiner’s Creek (1885), Tom Roberts. Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

However, Australia’s position on the international stage is important in the exhibition, which ends with a fourth artist, John Russell. Long written out of the history of Australian art, his vivid, audacious use of colour and divergence from the practices of his Australian contemporaries is an interesting conclusion. At first glance Russell’s inclusion in the show seems incongruous – he was an Australian national who spent most of his working years in France and was deeply invested in avant-garde colour theories and European landscapes. However, his artistic practice is important in exploring not only Australia as a subject but also what it meant to be an Australian artist. Russell was close to fellow artists Toulouse-Lautrec and Van Gogh, but he also maintained regular correspondence with Streeton, sending back news of Europe’s artistic innovations (often disregarded by Streeton who found his approach too technical). Russell’s landscapes are bright and hallucinatory, occasionally even veering towards abstraction. The artist’s largely underappreciated work, including the remarkable A Clearing in the Forest (1891), is worthy of reassessment.

A Clearing in the Forest (1891), John Russell. Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

![A Clearing in the Forest [Belle Ile], 1891](http://new-dev.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Australia-X9152.pr_.jpg?resize=723%2C800)

The exhibition’s intimacy (there are around 40 works on display) offers a unique opportunity to experience the work of these four Australian artists more thoroughly and uncovers the intimate interactions between them –including Roberts’ and Conder’s Coogee Bay scenes, which were painted side by side and now displayed in the same way. Yet it can also seem restricting at times. There are significant omissions: there is no sense here of the extent to which these artists engaged with Aboriginal culture (if at all), while interesting links, such as the influence of Japanese prints, are mentioned but remain unexplored. This limited survey acts as an introduction – a strong and impressive one – but one that leaves the viewer with only a partial view of what it was to be an Australian Impressionist.

‘Australia’s Impressionists’ is at the National Gallery, London until 26 March 2017.