Georges Seurat’s Les Poseuses, Ensemble (Petite version) (1888) is a painting that packs a big punch. As part of the much-trumpeted sale of works from the collection of Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen at Christie’s Rockefeller Center in New York next week, it also comes with a vertiginous price-tag. More than $100m is expected for this little canvas of just 40 by 50cm, which could fit 25 times into the ‘big’ version held by the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia. What that painting might now be worth one almost fears to think.

The Allen sale is set to become the first in history to break the $1bn barrier – a feat which has, at least since the sale of the Macklowe collection at Sotheby’s peaked out at $922m across two sales in November 2021 and May this year, come to seem in some quarters of the art-market press as something akin to the four-minute mile. With 100 per cent of the lots up for sale across two marquee evening sales on 9 and 10 November guaranteed, however, the result here is rather more of a foregone conclusion.

Christie’s suggests that the importance of Allen’s collection, amassed largely between 1992 and 2006, lies in the ‘comprehensive study of the art historical canon’ it provides – hyperbole which doesn’t really do justice to the inherently partial (and personal) nature of all private collections, even the greatest ones. The latter, shaped with an eye to the whole, manage to be more than the sum of their parts. It seems fair to say that Allen’s collection is better described a series of big-hitters than a team working in tandem.

Madonna of the Magnificat (early 1480s), Sandro Botticelli. Christie’s New York (estimate on request)

Still, these big-hitters are impressive enough in their own right. They include Botticelli’s Madonna of the Magnificat tondo, reportedly expected to sell for around $40m – a variant of versions held by the Uffizi and the Morgan, described by Herbert Horne as the painting which more than any other has ‘gone to fix the popular notion’ of Botticelli’s work – as well as major works by Turner and Jan Brueghel the Younger. Perhaps the greatest treasures are to be found among Allen’s impressionist works. The Seurat is one of three works expected to pull in more than $100m – the others are a spring landscape by Van Gogh, painted a couple of months after he arrived in Arles in February 1888, the tentative blossom of the cypress appearing here as a symbol of his own artistic renewal, and one of Paul Cézanne’s earlier depictions of the subject that would preoccupy him more than any other for the remainder of his life, the Mont Sainte-Victoire in Aix-en-Provence (est. in excess of $120m).

There is a dazzling landscape by Paul Signac (est. $28m–$35m) – pointillism in the service of the shimmering reflection of boats on the water at dawn – and a work by Manet depicting the Grand Canal in Venice, unusual for the intensity of its blues. From here, the story extends forwards to take in major works by Klimt, O’Keeffe, Magritte, Bacon, Freud – the latter represented by a fine, if strangely unfinished-seeming, group scene in a London interior after a composition by Antoine Watteau – and on to Jasper Johns, Agnes Martin and Louise Bourgeois.

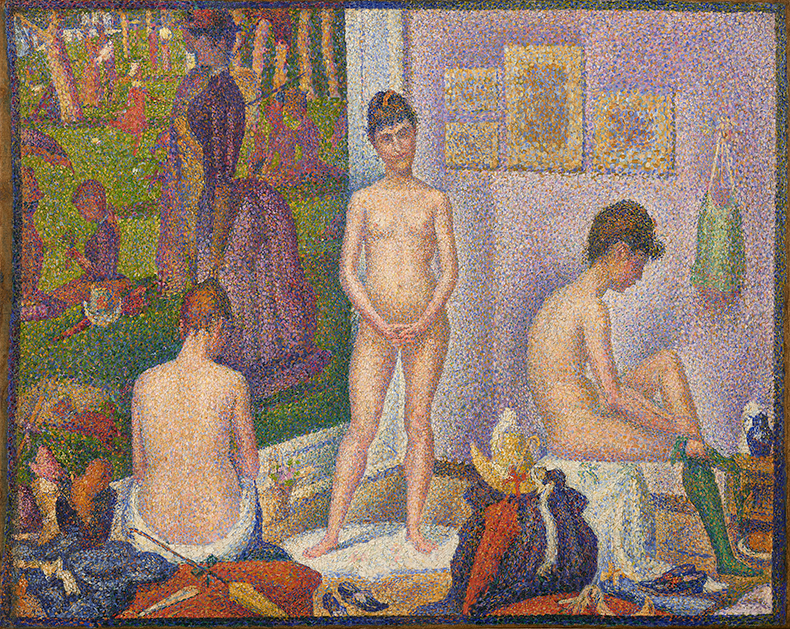

Les Poseuses, Ensemble (Petite version) (1888), Georges Seurat. Christie’s New York (est. in excess of $100m)

Les Poseuses, to my mind, is the pick of them. This was Seurat’s grand riposte to those critics who, having seen A Sunday on the Grande Jatte (1884–86), questioned the aptitude of pointillism for noble subjects such as the nude. The figures, they said, were too rigid; so, with Les Poseuses, Seurat gave them three nudes in an array of classical poses – one with her back turned, another standing to face the viewer, and a third in profile, either taking off her stockings as though having just entered the room or pulling them on as though to leave it. The combination of complementary colours that was a hallmark of pointillism – here, blues and greens with reds and oranges – gives their skin a purpled shimmer, in harmony with the walls behind them. Behind the figures – perhaps a painting hung in the studio or, a more compelling possibility, a scene spied in reality through an open window – is the work Seurat described as his ‘manifesto’, the Grande Jatte itself. If Les Poseuses is, in some respects, Seurat showing his critics that he’s been listening to them, he nonetheless didn’t miss the opportunity to show them he was doubling down on his convictions.

Collage (1950), Willem De Kooning. Sotheby’s New York (est. $18m–$25m)

The Allen collection isn’t the only high-profile single-owner sale coming up this month. Sotheby’s counters with the collection of David Solinger, an art lawyer who represented the likes of Franz Kline, Hans Hofmann and Louise Nevelson. The top lot is a spectacular work by another close friend of Solinger’s, Willem De Kooning; his Collage (1950) is unusual among his oeuvre for the fact that, as its name suggests, it is comprised of chopped-up strips of painted canvas, thumbtacks dotted across the composition (est. $18m–$25m). More than $100m is expected for the Solinger collection – it feels bizarre to consider that this sum, compared with Allen or Macklowe, is now second tier. But as the result both of inflation and the rampant proliferation of billionaires worldwide since the 1990s, this could be the new norm for a long time to come.

In London, meanwhile, comes a sale that offers an insight into workings of the art market below these heady heights. Jan Finch began her career as a dealer in the Portobello Market in the 1980s, selling an eclectic range of sculpture, antiquities and art from Africa and Oceania; Finch & Co’s gallery (and latterly their stalls at art fairs) became renowned as a kind of wunderkammer that marked their displays out from the rest. Finch died last year, leaving the business to her husband, Craig Finch; now, 400 works from her estate are up for sale at Sworders on 9 November. At Stair Galleries, New York, comes a sale on 16 November that likewise reveals a life in objects; works from the estate of the writer Joan Didion, including paintings by her friends in California such as Richard Diebenkorn, Sam Francis and Ed Ruscha, as well as her writing desk, books and ephemera. On a somewhat smaller scale, Dreweatts offers a new work by the Margate-based artist Ann Carrington – part of her long-standing series of Pearly Queen works that reimagine the portrait on a postage stamp, it consists of pearl buttons hand-sewn on black linen and is being sold on 22 November to raise money for the Queen Mother’s Clothing Guild.