Wangechi Mutu

‘I believe art is an ancient language that we use to communicate with each other into the future,’ Wangechi Mutu told the audience assembled for her TED Talk earlier this year. ‘We’ve left messages for each other using art. Messages that travel across the expanse of time and culture, reminding us of where we come from.’ This temporal hopscotch – jumping from prehistory to an imagined future – is characteristic of the Kenyan-American artist, whose work features motifs that range from folk symbols through to human-animal-plant-hybrids. It’s unsurprising that Mutu first moved to New York to study both art and anthropology.

Earlier this year, the results of this fertile cross-cultural and cross-disciplinary grounding could be seen throughout ‘Wangechi Mutu: Intertwined’, an exhibition at the New Museum in New York (2 March–4 June). This was the largest survey of the artist’s work to date, and a rare instance in which the whole building – including facade, lobby and hallways – was filled by the work of one artist. Mutu has long been praised by critics, but with the New Museum show, her work received much wider public acclaim.

Wangechi Mutu. Photo: Khadija Farah

The show told the full story of her 25-year career, ranging from early collage works, created in part through economic necessity – magazines, scissors and glue being cheaper to come by than most art materials – through to recent bronze sculptures on a monumental scale. ‘I never expected to go from the little collages and postcard works to these bronzes, but I did,’ Mutu told co-curators Margot Norton and Vivian Crockett for an interview published in the exhibition catalogue. The transition makes sense: an opportunity to combine the Western traditions of statuary and the metal workmanship established in Africa prior to European colonisation (‘It is such a strong, ancient material that has most likely been used in Africa for thousands of years’).

Nowhere have Mutu’s bronzes been more visible than on the facade of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, where from late 2019 to late 2020 a series of new sculptures filled niches that had been empty since 1902. Each of the four figures bore mirrored disks on their heads or faces, riffing on the large lip piercings worn by the Mursi and Surma women of Ethiopia. Their poses recalled both West African prestige stools, in the form of wooden figures that symbolically bear the weight of kings, and the caryatids of Greek and Roman architectural tradition. Each piece weighed 840 pounds and had to be lifted in place with a crane.

Grand works such as these and those humbler collages of Mutu’s earlier career are united by the artist’s interest in the idea of mixing – both literally, in the mixing-and-matching of visual sources ranging from medical manuals to National Geographic, and as a guiding principle for her exploration of cultural identity. ‘I was very conscious of my otherness,’ Mutu has said of her early years in the United States. ‘It never left me. So I try to make an integrated whole out of various parts.’ This artistic and emotional strategy appears across the wide range of media the artist has explored over the last quarter-century: performance works, videos, paintings, drawings, installations and sculptures.

Hybrids of every imaginable kind appear throughout her oeuvre. At the New Museum, two women-trees with roots for feet and leaves for heads sat companionably beside cafe-style tables and chairs in the lobby. In the galleries upstairs, artworks featured hyena-headed figures with snakeskin legs; a flying snake with an elephant’s body; women with wheels or mushroom stalks in the place of limbs. Sculptures such as MamaRay and Crocodylus (both 2020) depict imagined goddesses – chimeras of women with, respectively, a manta ray and a crocodile – which draw on references ranging from the zoomorphic deities of ancient Egyptian mythology to the nguva, a seductive sea-woman from East African folklore. ‘Among the reasons Mutu’s work resonates so deeply is in its expansiveness, multiplicity, uncontainability,’ Vivian Crockett tells me. ‘It acknowledges specificity but defies containment, and emphasises the interconnectedness of our histories, cultures and struggles.’

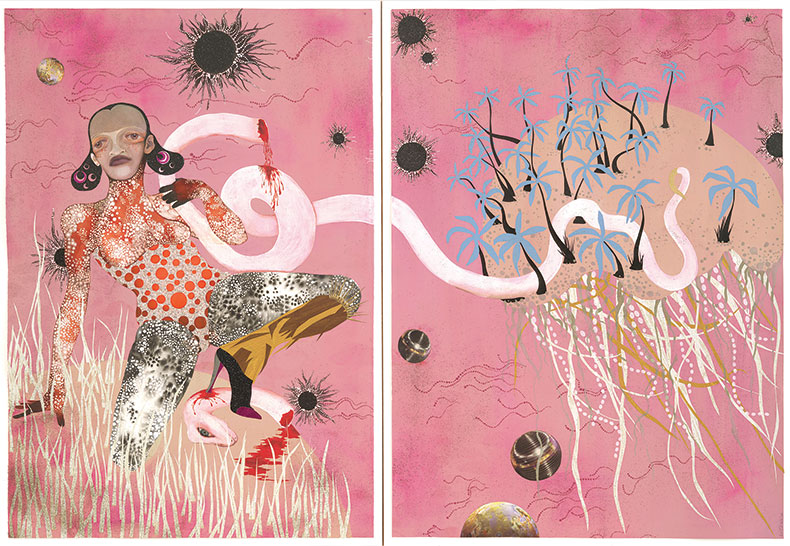

Yo Mama (2003), Wangechi Mutu. Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo: Robert Edemeyer; courtesy the artist and Vielmetter Los Angeles; © Wangechi Mutu

In this, Mutu’s work recalls the fantasies of Afrofuturism: a movement in music, literature, film and art that imagines possible futures through a Black cultural lens. Mutu’s figures, however phantasmagorical, are invariably recognisable as both Black and female. In the diptych Yo Mama (2023), a woman pierces a phallic pink snake with her stiletto heel, her realm orbited by both planets and disco balls. In his movie of the same name (1974), Sun Ra stated that ‘Space is the Place’ – but for Mutu, it’s more often the stuff of this earth that sparks inspiration. When, in 2015, she returned to Nairobi from a long sojourn in New York, she started working with natural materials – shell, bone, horn, soil, wood – sourced from her studio’s surrounds. These she uses to create works in which cowrie shells become eyes, logs become legs, and the rust- red soil of the Kenyan highlands is shaped like clay, that most ancient of materials, to create futuristic sculptures of women-tree hybrids or the geometric forms of viruses. As Sun Ra said: ‘The first thing to do is to consider Time officially ended.’ Ended, that is, in order to be remade anew.