From the September 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

I was arrested by the breast. Full, slack, laced with veins the liverish grey of an ebbing bruise, it erupts through pristine white cotton, the head above cropped from view. Locked on to its nipple is a baby, not fully unfurled, drowsily satisfied. Lucian Freud’s Esther and Albie (1995) is a portrait of the artist’s grandson in which the artist’s daughter’s body appears as a prop. Freud seems fascinated by the latter (reduced here to a supporting hand and sustaining bosom) and to relate enviously to the position of the former. Exhibited at his grandfather Sigmund’s former home in Hampstead, it is hard not to ponder what the elder Freud would make of the dynamics at play.

Breastfeeding – not as iconic Marian fantasy, but sticky reality – is an uncommon subject for painting. Despite the hundreds of hours mothers spend nursing, its hands-on nature precludes self-portraiture, as does the stormy transformation of life as a parent. With birth comes new perspective: where does one body end and the other begin? How to construct an identity separate from the child? Time is both endless (the broken nights, the repetitive tasks) and horrifyingly constrained (how to steal moments for a shower?). For artists who are mothers (time-greedy painters and sculptors in particular), the barriers to restarting work are forbidding. In the early years, art happens in fragments, fitted around naps and feeds. Later, if they can afford or negotiate childcare, there might be a few hours at a stretch. But long, luscious days of focus are gone – at least for a time.

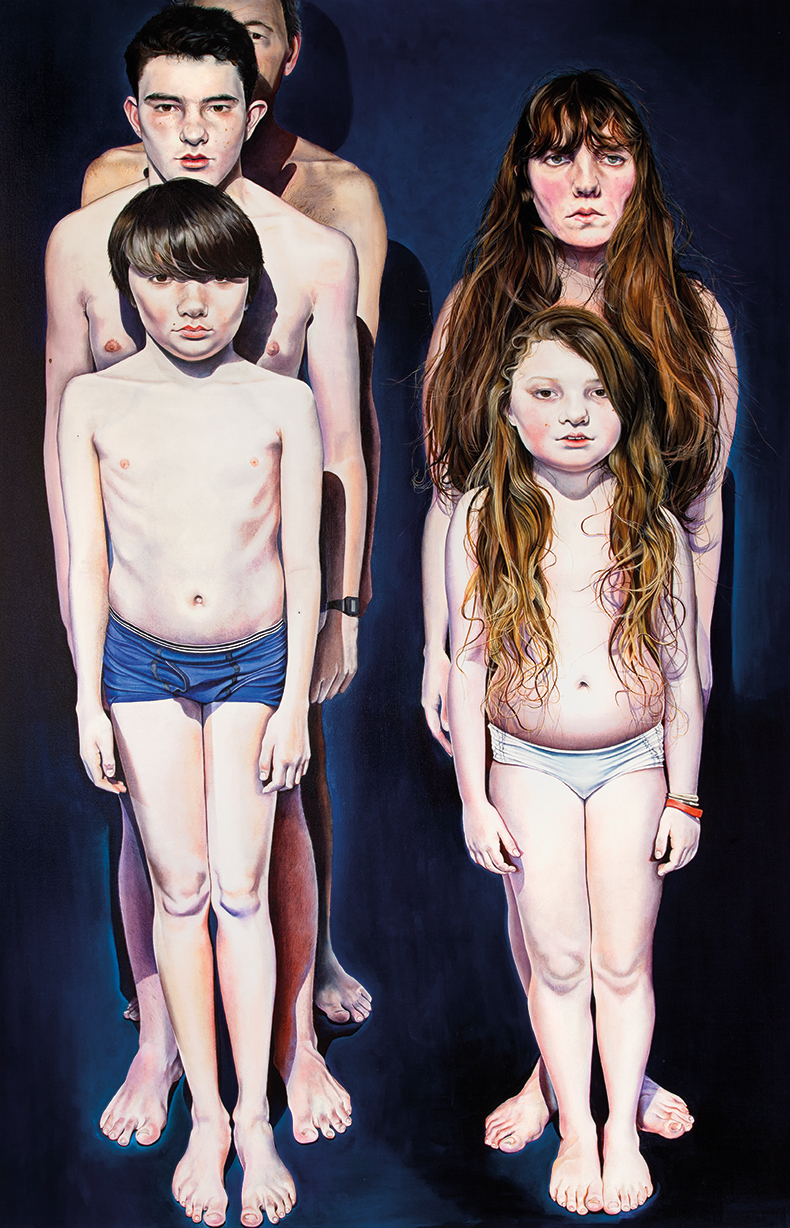

Freud’s vantage point was that of a hands-off parent. One son, Alex Boyt, recalled sitting for his father as the only way to spend time with him. He painted his children at a distance from intense interdependence. I might once have described this distance as a luxury, but visiting the Freud show after writing a book on mothers in the art world, it felt more like emptiness. There was little sense of the divided self, the claustrophobia, the fury, frustration, exhaustion and wonder that an active parent might bring to painting their children. I thought of Ishbel Myerscough’s family portrait All (2016): five figures stacked in two rows, suspended in shallow indigo space, the bodies blocking and doubling one another, pushing at the confines of the painting. I thought of her portraits of her children, with their intense, luminous, outsized presence. They dominate the view, as children do when you are responsible for keeping them alive and OK.

All (2016) Ishbel Myerscough. Courtesy Flowers Gallery, London

With body, thoughts, lines of sight thus dominated, artist mothers have long turned to their children as subjects. It seems each generation faces a new objection to such work: one had the subject of motherhood dismissed as unserious; another endured a scandalised frenzy over child nudity. Today, artworks featuring children are being judged in the light of social media. How might a child later feel about the public documentation of their infant years? Should we reconsider sharing images of children too young to give consent? Images leave our control once on Instagram: is it OK to post pictures of children knowing they may float free of context? What about professional Insta-mums, who promote sponsored brands and repackage childhood as advertising in real time? Some mothers now feel they have no right to show art featuring off-spring not yet old enough to provide informed consent. They shield faces from view, or commit to setting work aside until their children can agree to its public exhibition and sale.

The Virgin Mary haunts us through more than maternal iconography. Marina Warner’s cultural history Alone of All Her Sex (1976) charts the centuries over which mothers in the Christian world have been held up to impossible standards of purity. As an ideal, they were offered a compliant figure, defined by service to her son and free from sin: a virgin not only before, but also after birth, whose milk performed miracles and whose body did not age before death or decay after it. Contemporary acts of abnegation – an artist refusing herself the child as subject, or patiently withholding an image until they come of age – are declarations of maternal purity that join a long lineage of public selflessness. By default, they also position the artist/model relationship as exploitative. This runs counter to another recent art historical tendency. Exhibitions such as ‘Whistler’s Woman in White: Joanna Hifferman’ at the Royal Academy of Arts remind us that the role of artist’s model is an active one. Rather than artists fretting that their work exploits their children, might they not see this participatory role as enriching and collaborative?

Andi Galdi Vinko’s photo book Sorry I Gave Birth I Disappeared But Now I’m Back, published this month, testifies to the continuing power of artists to picture motherhood and early childhood in unexpected and affecting ways. Here is tenderness, disgust, radiance, streaks, stains and relentless proximity. Sitting on the loo in night darkness, we follow the artist’s gaze across the margin of her lowered knickers to meet the eyes of her baby daughter, alert, at her feet. ‘Where is my village,’ she writes, next to a child wet-cheeked with tears. There is much squishy flesh and bare skin, for such is intimate life with small children. This book is part of the complex and necessary counter narrative to the latest generation of maternal purity, but also to centuries of mothers and children pictured across the emptiness of carefree distance.

From the September 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.