As the already saturated internet continues to be flooded by new content, how can we hope to continue being able to navigate it? ‘The Algorithmic Pedestal’ a new exhibition at J/M Gallery in London, tries to address this problem by considering how algorithms have been entrusted with a role not unlike that of art curators, filtering the deluge of digital ephemera to determine what we actually see. But, the exhibition asks, who really benefits from ‘algorithmic curation’?

The show is the culmination of doctoral research by Laura Herman, from the University of Oxford’s Internet Institute. Herman recognises that social media has long been an invaluable and accessible tool for artists – especially those not represented in museums or galleries – to build their public presence. For some time, creatives of all kinds have been able to amass large followings on blogging sites such as Instagram and Tumblr by providing a steady scroll of images, together representing an idiosyncratic creative vision. However, more recently, in a move led by TikTok and imitated by other platforms, each user’s feed has become a unique, hyper-niche offering dictated by the preferences inferred from past actions – skips, likes, comments and shares – all calculated by a mysterious ‘black box’ algorithm.

Even if I choose to follow a curator whose expertise I trust on social media, I am highly unlikely to see everything they post, since certain kinds of content are suppressed by the algorithm. Inevitably, this has forced creators to adapt their practice according to the algorithm’s elusive, ever-changing needs if they have any hope of reaching a wide audience. An artwork has a better chance of being promoted if it has more faces and less nudity, for example, with the latter banned on many platforms.

‘We are returning to this model of one entity deciding what we see,’ Herman explains. ‘In the past those entities were museum curators and gallery owners, now algorithmic platforms are playing that role.’ With little transparency to how these algorithms have been trained, both the cause and the effect of these changes to how we experience information online remains tricky to perceive.

Instagram profile created for ‘The Algorithmic Pedestal’ (@thealgorithmicpedestal)

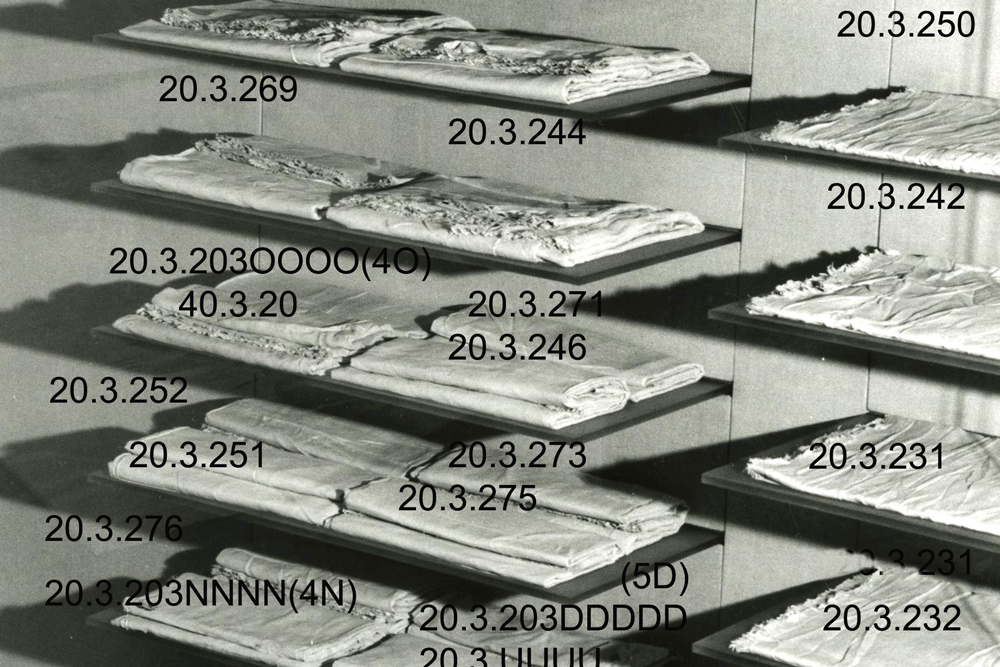

‘The Algorithmic Pedestal’ is, in fact, two exhibitions, staged side by side. Both are drawn from images from the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Open Access Initiative , which, since 2017, has made all public-domain works in its collection available for unrestricted use. One exhibit is curated by London-based Swiss artist Fabienne Hess on the theme of loss; the other by the Instagram algorithm (the images were uploaded to a dedicated Instagram account and the exhibit reflects which images the algorithm chose to display and in what order) .

Although there was no overlap in the images chosen, Herman has been able to make a number of intriguing comparative observations. Works selected by Instagram show a marked preference for bodies and faces. Herman also observed ‘commercial-looking’ photography in the style of an advertisement or a sales catalogue, presumably reflecting profit-driven rather than aesthetic interests.

Perhaps most importantly, each image picked by Instagram was a standalone image with no apparent overarching context.By contrast, Herman sees in Hess’s grouping ‘a unified set of images that tell a story and have metaphor and exist within a context’. Both Hess and Herman stress how ‘loss’ is a very human, personally felt concept that is hard to describe and open to different interpretations. ‘A lot of human curiosity is around what prompted an image – what was the underlying idea?’, Hermann adds. When we think about curating, we usually seek out that same sense of a guiding intelligence.

Louis Revoil (1865–75), André-Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri, selected by Fabienne Hess for ‘The Algorithmic Pedestal’

The nature of loss defies easy categorisation. Hess contrasts it with the straightforward image labels – ‘dog’, ‘cat’, ‘woman’ – on which Big Tech relies to train AI to see and understand images. Such labels have proved a contentious topic, raising concerns over the replication of human biases and the failure to secure consent, but Hess makes the case that this crude method also risks draining our world of slippery notions and nuance.

The influence of the algorithm is only growing. Late last year, Mark Zuckerberg promised that by the end of 2023 he will ‘more than double’ the 15 per cent of our Instagram feeds that is currently delivered according to AI recommendations. ‘In the realm of the arts, there are often considerations of novelty and originality that algorithms aren’t equipped to account for,’ Herman says. ‘The algorithm would be focused on questions such as: Where does this slot in? What is it similar to?’ Thoughtful curating should come up with a surprising response to these problems and become a creative act in itself.

‘The Algorithmic Pedestal’ is at J/M Gallery, London, until 17 January.