From the October 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

After its traditional summer break, the art market got off to a flying start last month with the launch of Frieze Seoul. It is the London-based art fair’s first foray into what has been in recent years a burgeoning Asian art market. Sales were, according to some galleries, strong. But, despite the optimism in Korea, there is a growing nervousness about the effect a predicted global downturn might have on the art market’s post-pandemic bounce-back.

In July, the International Monetary Fund downgraded its global forecasts and said nations must tackle inflation and cut debt, even though ‘tighter monetary policy will inevitably have real economic costs’. The gloom deepened at the Jackson Hole meeting of central bankers in August. Jerome Powell, Chair of the Federal Reserve, told his international colleagues ‘to take the pain now’, even if it leads to recession.

Marc Glimcher, who heads mega-gallery Pace, was in Seoul to launch its expanded exhibition space. The investment is a mark of his confidence in Korea, he tells me, which he describes as ‘the best of Asia with the best of California, laid-back and fun to deal with’. Nevertheless, ‘We are looking at a very difficult couple of years ahead, and of course the art market will be impacted,’ he says.

Susan May, global artistic director of White Cube which will open a three-floor gallery in New York next spring, agrees. ‘The coming months are going to be challenging for many businesses, and that does not exclude the art world,’ she says. ‘We’re seeing increased running costs and energy bills, and more expensive raw materials and transportation. We are absolutely affected by wider shifts in the economy.’

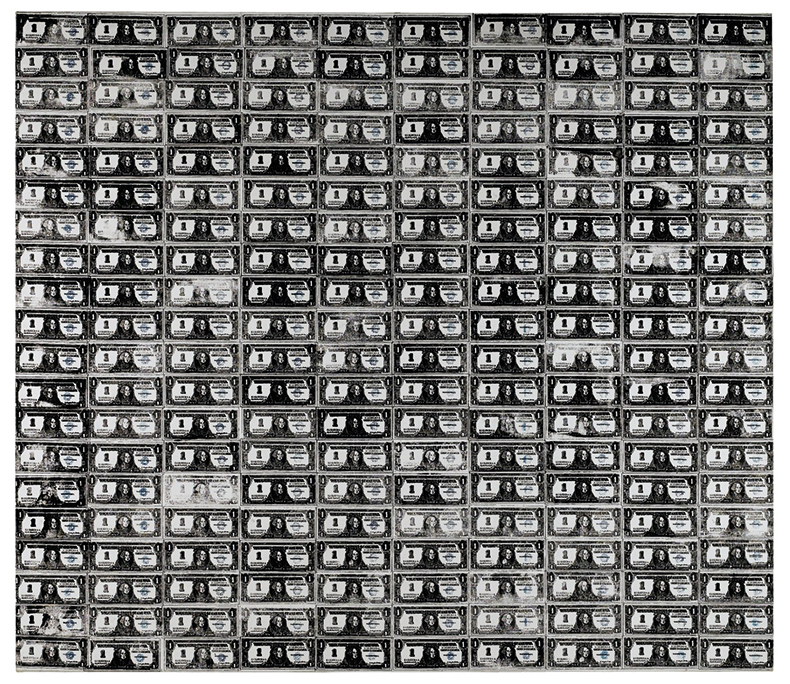

Andy Warhol’s 200 One Dollar Bills (1962) sold for $43.8m at Sotheby’s New York in November 2009. Photo: © 2022 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./ Licensed by DACS, London

There have been four big global recessions since 1950 – in 1975, 1982, 1991 and 2009. The last one was the deepest, with ‘the weakest recovery in the years since in advanced nations and the strongest in developing economies,’ according to the World Bank.

Economist Clare McAndrew, founder of Arts Economics, has compiled data that shows how closely art sales mirror these downturns. In 1990 they reached $27.2bn, but fell back dramatically to $9.7bn in 1991. It took 14 years for the art market to surpass that 1990 high. In 2008, sales were at $62bn, only a little under the peak of 2007. They fell sharply to $39.5bn in 2009, but bounced back to $64.3bn just two years later. Weaker recovery in traditional markets such as the United States and Europe was compensated for by faster growth in Asia, especially China.

In previous recessions it was common to hear claims that the art market was immune to the financial chaos – possibly because, for several months, it was true. It can take time for a downturn to really show.

In 1990, a combination of the Gulf War, the declining Soviet Union, an asset-price bubble in Japan, the European Exchange Rate Mechanism in the EU and a US credit crunch combined to create what would become a global downturn. The art market was at a peak, fuelled by a decade of money flooding into Wall Street and the surging Japanese yen. New York financiers had gone crazy for the likes of Julian Schnabel and David Salle, while Japanese buyers pushed prices for Impressionist painters up by 940 per cent in just 10 years. In May 1990 in New York, Christie’s sold Vincent Van Gogh’s Portrait of Dr Gachet (1890) for $82.5m to Japanese paper manufacturer Ryoei Saito. At the time it was the highest price paid for a work of art at auction.

James Roundell, director of Impressionist and modern art at London- and New York-based gallery Dickinson, was then head of Christie’s Impressionist and Modern department in London. ‘After Japan’s crash started, we had a sale in June in London, we had some good things and it was pretty successful,’ he recalls. ‘Sotheby’s sale was relatively poor, but we thought, aren’t we clever? We understand the market, we’ve got the better things, we’re fine. What we didn’t quite get was that the market was collapsing around us. Come the autumn, you couldn’t say a picture was worth 10 per cent less or 20 per cent less. It was whether it sold at all.’

In spring 2008, the credit crunch was already well under way – a result of loosening financial regulation, international credit booms and the expansion of high-risk lending, particularly in US mortgage markets. Problems at banks including BNP Paribas, UBS and Northern Rock had sent up red flags the year before: in March, the 85-year-old New York investment bank Bear Stearns avoided bankruptcy only after a fire-sale to JP Morgan Chase. But it was business as usual in the art market, with strong sales at the Armory Show art fair less than two weeks later.

Lehman Brothers collapsed on 15 September in New York. That night and the next day in London, Damien Hirst’s ‘Beautiful Inside My Head Forever’ sales at Sotheby’s totalled £111m for new – and some thought not terribly good – work. It was only at the New York Impressionist, modern and contemporary auctions in November that it became clear that confidence was cracking. The New York Times reported Eli Broad gleefully snapping up works by Jeff Koons, Robert Rauschenberg and Donald Judd at Sotheby’s, in what he was overheard calling ‘a half-price sale’.

What complicates the picture is that the art market is not really a single entity but a multitude of different markets. Cultural and social shifts mean that aesthetic tastes also change regardless of financial markets. In a recession, high prices can still be paid for in-demand artists or famous collections, just as interest in some artists can fade even in a boom.

In 2009, as the wider art market fell by a third, the collection of Yves Saint Laurent made €373.9m at Christie’s Paris. Andy Warhol’s 200 One Dollar Bills (1962), made $43.8m at Sotheby’s New York, more than three times its upper estimate. And while smaller galleries closed in London, New York and Berlin, Hauser & Wirth and David Zwirner continued to grow, with major new spaces in Manhattan.

In the late 1980s, taste was shifting from older art to the new – although no-one really knew it. Then, the market for École de Paris artists was so hot that records were set even for lesser known members. In 1989 a buyer paid $1.4m for a 1925 painting by French artist Marie Laurencin – her work typically sells now for less than $150,000. Van Gogh’s paintings routinely now sell for tens of millions. But 32 years on, $82.5m remains the record for his work – although US inflation means the value of that sum today would be more than double and the art market is now more than twice its 1990 size.

But what happened in the past is not a guarantee of what will happen today. Canice Prendergast, professor of economics at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, believes that the art market has fundamentally changed. ‘The market doesn’t track the economy any more, it tracks wealth, and that has changed hugely, even in the past two years,’ he says. The status of art as an asset and as a luxury has also risen for the wealthy, who anyway aren’t hit by cost-of-living and inflation crises. ‘Art has become a globalised status commodity in a way it has never been before,’ Prendergast says. ‘Even when the stock market tanks, wealthy people think, well, maybe I’ll buy a painting.’

Wealth distribution is a complicated subject – as are attitudes to spending on art. What is clear is that number of wealthy people has increased worldwide, at the same time as the art market has grown and internationalised. Forbes estimates that the number of billionaires rose tenfold between 1990 and 2008, and has more than doubled again. They are also even richer: 2,668 people hold $12.7tn, three times more than the 1,125 billionaires held in 2008. Where they are based has also changed – from a group largely based in the United States and Europe to 75 countries today. Consultancy firm Capgemini, meanwhile, reports that the number of high-net worth individuals – people with more than $1m in liquid cash to spend – has also shot up. In 2008, 8.6m people held $32.8tn. Now there are 22.5m, holding nearly $86tn.

Vincent Van Gogh’s Portrait of Dr Gachet is sold at Christie’s New York for $82.5m in May 1990 Photo: Ray Stubblebine/Reuters Pictures

Of course, many of these people do not buy art. There’s no escaping the fact that the art market is in for an anxious autumn. Nevertheless, the mood of London art galleries ‘overall is good,’ says Paul Hewitt, director general of the Society of London Art Dealers. But it is clear a lot is riding on the success of fairs such as Frieze London, Paris+ par Art Basel and Art Basel Miami Beach – not to mention the ‘marquee’ art auctions in London in October and in November in New York. Hopes are high for the success of single-owner auctions including the collections of Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen and philanthropist Sir Joseph Hotung which – like the YSL sales in 2009 – inject confidence into the market.

Privately, insiders express concerns about less deep-pocketed mid-market and younger galleries and what several called ‘speculative bubbles’ around some emerging artists. There is also a growing list of smaller art fairs that appear not to have made it through the pandemic. Last month Artnet reported that sales recorded in its global art auction database between $1m and $10m fell sharply from 2021, suggesting the market is softening.

Nevertheless, seasoned galleries say they have been here before. May says that White Cube, which was founded in 1993, ‘is hopeful [in the] longer-term,’ adding that ‘we have persisted through previous periods of financial volatility’. Glimcher, whose father opened Pace in 1960, says: ‘We are still the tiniest branch of the arts economy compared with huge mature industries like music and film. We have blue sky ahead even if now is a challenge.’

Roundell suggests a long memory in the art market puts things in perspective. ‘In 1990 it was like stepping off a cliff, but in 2008, the top end of the market was hardly affected,’ he says. Barring a massive geopolitical crisis, such as China invading Taiwan, he adds, ‘This time I think we will pretty much sail through.’

From the October 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.