Chicago is midway through a year-long, city-wide initiative, Art Design Chicago, propelled by the patronage of the Terra Foundation for American Art, which has its headquarters in the city. More than 30 exhibitions – most of them backed up with new scholarship, publications and public programmes – are inspired by the period since Chicago’s phoenix-style rise after its devastating fire in 1871. Throughout that period, thanks to its railways, canals and rivers, the city was at America’s commercial, manufacturing and artistic crossroads. It welcomed and sent out new ideas; it was a destination for immigrants both from abroad and other parts of America.

The mission of the Terra Foundation, which businessman and art collector Daniel Terra (1911–1996) founded in 1978, is to foster engagement with American art of all periods both nationally and internationally. Terra, a first-generation Italian immigrant, believed that experiencing original works of art could be transformative. To this end, he put some of his substantial art collection dating from the colonial period to 1945 on public exhibition in a new museum in Chicago in 1980, and opened a second museum of mostly American Impressionist paintings near Monet’s house at Giverny in 1992. After Terra’s death, the foundation’s staff reconsidered how to realise his mission. They closed the Chicago museum in 2004 to make it an 800-piece lending museum without walls – around 20 per cent is usually out on loan. They inaugurated a grants programme in 2005, opened the Paris Center & Library for research in 2009, and in 2014 transferred the Giverny museum to a group of public regional authorities working in partnership with the Musée d’Orsay.

Untitled (Lady with a Cat) (1961), Gertrude Abercrombie

The idea for Art Design Chicago was hatched by Jennifer Siegenthaler, who oversees programmes, education grants and initiatives at the foundation. ‘It is the result of listening to locals for 15 years,’ she says. ‘So many had ideas for shows on the history of art and design in Chicago that they could not do.’ So, starting in 2012, the foundation began to fund ‘research, deep research’ and development, so those ideas could be realised. More than 30 grants have been awarded. The Arts Club of Chicago – which in 1923 hosted Picasso’s first US exhibition – was able to produce the show ‘A Home for Surrealism: Fantastic Painting in Midcentury Chicago’ (until 17 August), gathering some 40 paintings on loan by Gertrude Abercrombie, Eldzier Cortor and other local artists to reveal this little-known movement. At the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) Chicago, curators had long wanted to dig deeper into their own collection; the result is an exhibition about the influential Chicago photographer Kenneth Josephson (until 30 December). His ‘picture fictions’, which layer different photographs, foreshadow the image manipulation of selfies, Snapchat and Instagram posts.

Chicago (1972), Kenneth Josephson. Photo: Nathan Keay; © MCA Chicago/Kenneth Josephson, 1972.

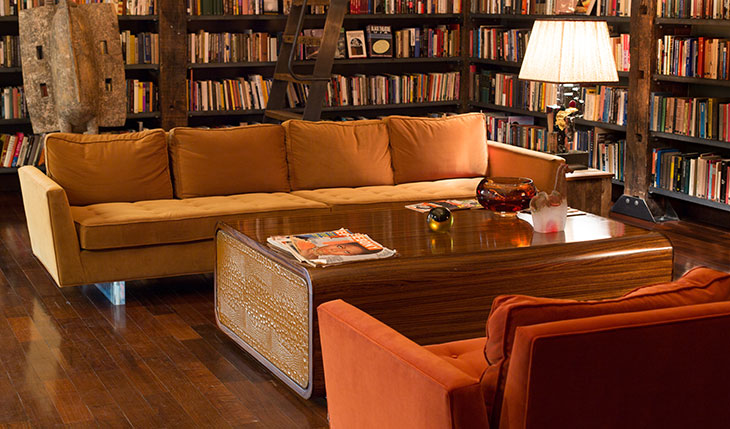

Many of the shows are in historic buildings scattered across Chicago, which are easy to reach thanks to the city’s public transport system. A visit to the Stony Island Trust and Savings Bank, completed in 1923, is worth it for the building alone. Taken over and saved from dereliction in 2012 by the artist Theaster Gates, it is now Stony Island Arts Bank, where Gates’s Rebuild Foundation holds cultural programmes and houses the remarkable archive of the founding publisher of Ebony and Jet magazines, John. H Johnson, in a beautiful upstairs library. Johnson is the subject of their Art Design Chicago show (until 30 September). As Gates says, ‘When you came to Chicago in the 1970s, you had to stop by at 820 South Michigan Avenue, the only building there owned by a black person. Everything was considered, even the trashcans. Each floor was colour-coded. We are re-imagining the bank as a 21st-century 820 South Michigan.’

Across in Pilsen, a predominantly Mexican neighbourhood known for its murals, Cesáreo Moreno is director and chief curator of the National Museum of Mexican Art, founded in 1982 and now holding some 10,000 works. ‘You can live your life here and never speak a word of English,’ he says proudly. Museum labels are in English and Spanish, entry is always free, and shows span Mexican art history and folk to contemporary. His show ‘Arte Diseño Xicágo’ (until 19 August) is an investigation into the art of Mexicans arriving in the city by train in the decades after the 1871 fire. ‘This is a dream exhibition,’ says Moreno. ‘It’s the story of our community through art. It shows how modern the artists were. It was often Mexican artists who decorated the new buildings.’ Filling a suite of big galleries, Moreno’s selection includes paintings, prints and photographs by sculptor Enrique Alférez, artist and art teacher Mario Castillo, printmaker Carlos A. Cortéz and photographer Maria Varela.

Installation view of ‘A Johnson Publishing Story’ presented by Rebuild Foundation at the Stony Island Arts Bank, Chicago, 2018. Photo: David Sampson

More than 75 cultural institutions are involved, often a well-established one working with an emerging one. Downtown Chicago has 22 colleges, most with their own museums (many with exceptional architecture – Mies van de Rohe designed the whole campus for the Illinois Institute of Technology). At the University of Chicago’s Smart Museum of Art, ‘The Time is Now! Art Worlds of Chicago’s South Side, 1960-1980’ opens in September. Its curators have plunged into the lives and output of African-American artists involved in the Black Arts Movement, researching pieces from the Smart’s holdings as well as lesser-known collections such as the DuSable Museum of African American History.

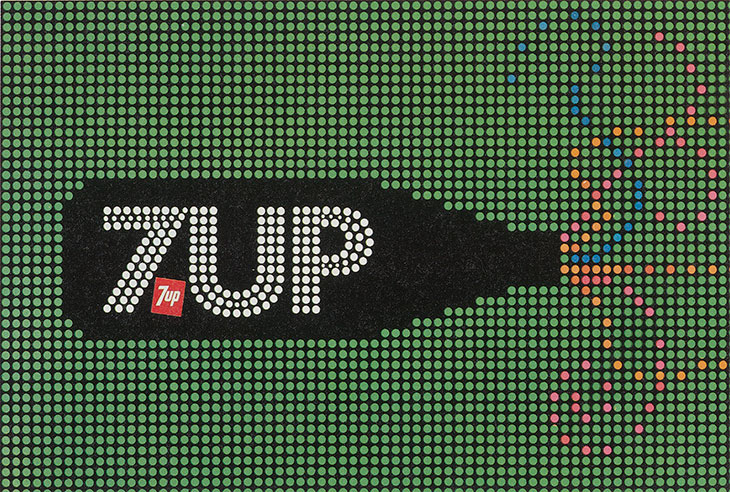

At Northwestern University’s Block Museum of Art, Terra Foundation funding has enabled director Lisa Corrin ‘to bring to light a forgotten chapter in our city’s cultural history’. Working with Chicago Film Archives, she has explored the experimental artist-designer-filmmakers Morton and Millie Goldsholl and their advertising firm Goldsholl Design & Film Associates, founded in the 1950s. ‘They were one of the most innovative Chicago design companies; they understood the importance of the logo,’ Corrin explains. Goldsholl created logo identities for Motorola, Revlon, 7 Up and many more. Inspired by Bauhaus philosophy, and convinced that art could be an agent for social reform, they made avant-garde films to convince the public their lives could be better by using the right products. They were not alone; throughout Chicago more than a hundred production companies were connecting art, industry, advertising and design – a newly collaborative way of working creatively.

7 Up billboard design for ‘See the Light’ Campaign (c. 1975), Goldsholl Design Associates. Courtesy Dr. Pepper Snapple Group

The Terra Foundation itself has also commissioned some new works. Some are for the riverfront theMART (the world’s largest building when it opened in 1930 as Merchandise Mart). This autumn, Art on theMART will transform its 2.5-acre façade into a digital art space showing local and international work for free all year round. At the polar opposite end of accessibility, it is worth every effort to nail a place on a tour of the artist-craftsman Edgar Miller’s Glasner Studio, which he rebuilt in the 1920s as an artwork of murals, stained glass, cabinetry and ironwork. The foundation is sponsoring a series of public lectures at the DePaul Art Museum on Miller’s work in the city.

Already, museums are acquiring new pieces from the shows for their permanent collections, and inter-institutional relationships are deepening. ‘Our aim is for everyone in Chicago to be involved, to engage people in conversations about art. We believe that art has the power to distinguish cultures and unite them,’ says Siegenthaler, echoing Terra’s belief. Moving from show to show, I found Chicagoans keen to correct the derogatory notion that the US comprises two coasts with a yawning gap between them. ‘This is the third coast,’ they say with pride, and Art Design Chicago endorses that.

For more information about its programme visit the Art Design Chicago website.