From the May 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Since the first commercial extraction of kerosene from shale by the Scottish chemist James Young in the 1850s, oil has seeped into every part of modern society, including the art world. Refined into liquid fuel and pumped into combustion engines, it mobilised people and commodities. Its resins, extracted and polymerised, produced the new materiality of the age of plastics. It transformed visual culture, both in fine art and beyond, as its constituent parts were synthesised into the new polymer emulsions and unique pigments of acrylic paints. Many of them – like the lightfast quinacridones first produced synthetically in the 1950s – became available to artists because of their widespread use in the automobile industry. Over the same period, oil and its derivative products have seeped into every part of the planet as well, from the atmospheric carbon dioxide which since the ’50s has been a known cause of global heating, to the microplastics that researchers now detect in every biological system from the digestive tracts of crustaceans in the deepest ocean to the human bloodstream.

Recent discussions about the cultural influence of the oil industry have been dominated, understandably, by concerns about ‘artwashing’. The term denotes the longstanding practice whereby corporate entities engaged in ethically dubious practices – from arms manufacturers and tobacco conglomerates to pharmaceutical companies and fossil fuel producers – have sought to launder their public image through programmes of cultural philanthropy. As the tide of public opinion begins to turn against oil company sponsorship in the arts, however, it seems important to remember that the relationship between oil money and modern art has never been one-sided. Just as oil companies have exploited the publicity value of the arts, artists themselves have admired as well as deplored the dynamism and scale of oil machinery and infrastructure, serving variously as the industry’s documentarists and hagiographers as well as its severest critics. If the art world is now engaged in a difficult process of divestment and disentanglement from its carefully nurtured relationships with the fossil fuel industry, it might be of some value to recall how that relationship developed, beginning in the early years of industrial sponsorship of the visual arts.

Such an account might begin in June 1934, when the critic Cyril Connolly was dispatched by The Architectural Review to report on an exhibition of new paintings by a star-studded array of modern British artists at the New Burlington Galleries. The interest of this particular exhibition lay less in the reputation of the artists whose work it put on display than in the new form of patronage it heralded. Here, among other works by their contemporaries, Paul Nash’s rectilinear view of Rye Marshes, Graham Sutherland’s near abstract landscape-cum-still life of the Great Globe sculpture at Durlston Castle in Swanage and Duncan Grant’s post-Impressionist view of St Ives from the Ouse could be seen side by side with the publicity posters they had been commissioned to design by the exhibition’s sponsor: Shell-Mex and BP Ltd, a joint venture of Dutch Shell and the Anglo-Persian Oil Company, trading as British Petroleum.

Kimmeridge Folly, Dorset (1937), Paul Nash. Photo: © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The brainchild of Shell’s suave publicity director, Jack Beddington, the exhibition appeared to many artists and critics as a lifeline in the moribund art market of the early 1930s, when the economic situation had seen private sales and commissions slowing to a trickle. Framed by the firm’s bold advertising copy (‘You Can Be Sure of Shell’), these modern landscapes had been commissioned to circulate as ‘lorry-bills’ on the sides of Shell’s fleet of vehicles. In its newspaper and magazine campaigns, the company highlighted its magnanimous decision to avoid cluttering the English countryside with fixed advertising on hoardings or billboards; for Connolly this forbearance served as evidence that Shell understood ‘the responsibility of big business to the land which makes it big’. The combination of modernist form and nostalgic English pastoral that animated many of the commissions – strangely empty of the day-tripper’s Shell-filled motor car and the tour-group’s omnibus – portrayed Shell and BP as the enlightened custodians of the nation’s contemporary cultural life as well as its unspoilt rural landscapes. ‘The founts of patronage now flow from business houses,’ Connolly gushed, ‘and none of these merchant princes have realised their responsibilities more than Shell.’ The oilmen, Connolly suggested, had begun to embody a new, commercial variety of noblesse oblige; they were, or might well become, ‘the Medici of our time’.

Shell’s campaign was a remarkable success, not only reputationally but also aesthetically and socially. It brought works of contemporary art out of the gallery, creating new audiences and helping to establish an eclectic yet consistent array of styles and techniques which would become the signature of British visual culture in the 1930s and ’40s. Partly, that had to do with an approach to the representation of landscape that drew on the legacies of Impressionist and post-Impressionist modernism coupled with a peculiarly English form of pastoralist nostalgia that now seems distinctively interwar. After the Second World War, as the iconography of the British nation began to shift away from pastoral idylls towards a future of high-speed motorways and space-age roadside services, Shell and BP began to take a different tack. Instead of employing established artists, they would nurture a new generation of rising stars. Rather than commissioning picturesque views, they would emphasise the energy and power of industrial technology.

Less well documented than the New Burlington exhibition of 1934, ‘The Artist’s View of An Industry’, which opened in January 1955 at the Royal Watercolour Society (RWS) in Mayfair, marked a decisive shift in the public representation of a sector now confident of its cultural clout as well as its economic significance. In the lead-up to the exhibition, Shell recruited several dozen painters from Britain, France, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Italy and Germany – many of them recent art school graduates – and invited them to visit and document the company’s plants, refineries, tankers and pipelines. The British contingent, the largest by far, included a roster of promising young artists, many of them at the beginning of highly successful careers, including more than one future Royal Academician and several members of the Royal Scottish Academy. David McClure visited Shell’s installation at Ardrossan on the Ayrshire coast, where he made sketches and watercolours of refinery tanks and pipelines winding along the shores of the Firth of Clyde. Michael Andrews produced a panorama of Shell’s chemical plant at Carrington Moss outside Manchester, while Euan Uglow and Bernard Cohen spent an inclement week nearby, at Shell’s Ellesmere Port refinery (‘I think Cézanne would have committed suicide in this country,’ griped Uglow). Derrick Greaves, Edward Middleditch and Donald Hamilton Fraser all spent time painting Shell Haven refinery on the Thames Estuary, with eclectic results ranging from Greaves’s quasi-architectural perspective of a distillation unit to Hamilton Fraser’s almost cubist interpretation of a solvent processing tank. Other notable participants included Diana Cumming, Alfred Daniels, Peter Coker, Iola Hallward, John Houston, David Michie and Frances Walker.

Storage Tanks and Pipes, Ardrossan (1954; detail), David McClure. Courtesy and © David McClure Estate

Even the composition of the selection panel for the exhibition – which included the directors of the Slade, the RCA, the Arts Council, the Edinburgh College of Art and the Tate Gallery – points to the soft power wielded by Shell and its industrial partners in the 1950s. Its international afterlife, meanwhile, implies the allocation of significant financial as well as cultural capital: nearly 100 paintings by the chosen British and European artists were exhibited at the RWS before going on tour, first around Britain, then to Paris, Zurich, Brussels, Cape Town, Johannesburg and The Hague. In Brussels – where it appeared under the title ‘L’industrie du pétrole vue par des artistes’ – Shell’s exhibition caught the attention of Guy Debord and his proto-Situationist group, the Letterist International. To Debord and his associates, the convergence of art and big oil suggested something out of the era of the Medicis, just as it had to Cyril Connolly 20 years earlier. Unlike Connolly, however, they did not mean the comparison as a compliment:

It’s hardly surprising that Royal Dutch Shell today, tomorrow Coca Cola or Frankfurters, should aspire to the laurels of Lorenzo de Medici. Every arms dealer plays the philanthropist, the guardian of the arts and sciences, the protector – as well as the producer – of widows and orphans.

As the references to Coca Cola and frankfurters suggests, the Letterists’ objection was less to Shell in particular, or even to the petroleum business, than to what they saw as the appropriation of artistic practice to the service of an increasingly global capitalism.

In 1955, Shell’s programme of artistic commissions took place in a moment of post-war technological triumphalism, in the wake of the Festival of Britain, the detonation of the first British atom bomb and the early stirrings of the space race. Inevitably, those attitudes were reflected in the paintings selected for display, in which the infrastructures of the oil industry tend to appear either neutrally, as the occasion for technical investigations of form and colour, or as almost abstract elements in the composition of a landscape. There are even hints of the industrial sublime in the towering chimneys and complex pipelines of these installations, to which Shell – with remarkable confidence – had offered young artists almost unrestricted access.

The fact that such transparency now seems unthinkable is an index of change in the relationship between art and the oil industry that long predates the emergence of climate consciousness and broader ethical concerns about the environmental and social impacts of fossil fuel extraction. By the 1970s, as deindustrialisation took hold in British communities and the discovery of oil and gas in the waters of the North Sea prompted a new oil rush, the situation had become more complicated. Some artists found ways of maintaining links with industry. The Artist Placement Group, for instance, founded by the conceptual artist Barbara Steveni in the mid 1960s, recruited both the art collector and Shell board member Sir Robert Adeane, who served as a trustee, and Esso’s employee relations director Tom Batho. Through its industry connections, the APG arranged artists’ residencies for its members, including a stint for the sculptor Andrew Dipper on the Esso tanker Bernicia in 1972. (Six years later the ship would be responsible for a serious oil spill while trying to dock at Sullom Voe terminal in Shetland.) Steveni’s husband, John Latham, meanwhile, was placed in the Scottish Office, where he undertook a multimedia psychogeographical study of East Lothian’s oil shale wastegrounds, tracing the industrial exploitation of crude oil back to its origin in the kerosene works of 19th-century Scotland.

Forties Charlie (1975), Fay Godwin. © Aberdeen Art Gallery and Museums Collections

As Britain’s oil industry shifted offshore in the ’70s, access for artists became more difficult. Fay Godwin, whose photographs of Forties Field in the summer of 1975 document the early days of the offshore boom, recorded the opposition she faced in gaining access, not least because of her gender. (She eventually documented sites belonging to BP, Shell, Conoco and the American ‘wildcat’ firm Hamilton Brothers.) Yet many of the artists whose work has explored the harsh conditions of deep-sea drilling have been women. Kate Downie’s The Flare Boom and Kittywakes Beneath North Alwyn A (both 1988), painted after a week-long residency arranged by the French oil company Total in 1987, are impressionistic accounts of the bizarre visual environment of a remote drilling platform. In the former, the ignition of waste gas produces a spatter of orange fire and black smoke against the grey Arctic skies, while the latter presents the bulk of the platform in fish-eye distortion on a vertiginously curving horizon.

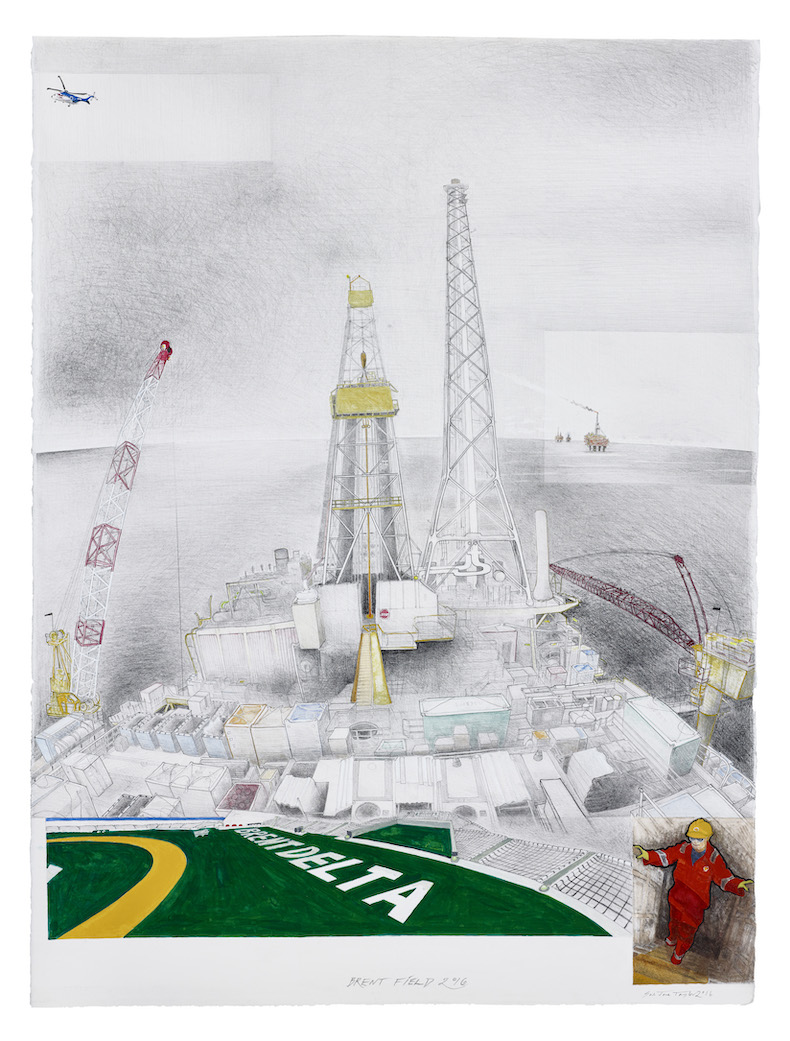

The same kind of curvature is visible, if less pronounced, in Sue Jane Taylor’s intricate The Brent Field (2016), which records the decommissioning of the Brent Delta platform between Shetland and Norway. It is a visual signature that efficiently suggests not only the isolation of the platforms themselves, but also their sheer size, which seems to preclude representation in terms of the traditional perspectives of land- or seascape painting. Taylor, who has recounted her shifting and sometimes difficult relationship with the industry in published diary extracts as well as in a remarkable body of etchings and drawings, undertook her first week-long residency on the ill-fated Piper Alpha in 1987, a year before the platform exploded, killing 167 oil workers. After the disaster, she came under pressure to sell her artworks to the platform operator, Occidental Petroleum: ‘I could name a price.’ In 1990 she was appointed to sculpt the monument to the disaster that stands in the Piper Alpha Memorial Garden in Aberdeen.

The Brent Field (2016), Sue Jane Taylor. Courtesy and © the artist

Compared with the industrial optimism of the 1950s, Taylor’s accounts of her relations with oil company management describe a very different environment for artists engaging with the sector in recent decades, yet also some continuities. ‘Few company managers have an understanding or appreciation of the arts,’ she writes. ‘However, if company managers can be persuaded to see an advantage in it for them – in terms of public relations and support for a local community – then at times they are happy to help.’ Unlike their mid-century predecessors, contemporary artists have had to thread the corporate needle, persuading their partners in industry of the PR value of their work while avoiding moral compromises of the kind Debord and the Letterists warned against, and which have been made yet more urgent by mounting evidence of the severe environmental impacts of fossil fuel extraction.

Not everyone has seen the situation in these terms. In ‘Energy’, an exhibition at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery in 2006, the museum rightly presented Fionna Carlisle’s portraits as a documentary record, a cross-section of the individuals involved in an economic sector, from rig workers and caterers to industry executives and politicians. Yet the exhibition catalogue also bore prominently the logo of its sponsor – the Total group of energy companies, one of the world’s largest producers of oil and gas. A foreword by the gallery directors praised the company (‘a particularly fortunate and fruitful collaboration’) as well as the ‘ingenious, enterprising, and intrepid individuals’ whose portraits were included. On the facing page, the managing director of Total boasted of the company’s importance to the UK economy and its generous support for ‘education, the environment, health, and of course the arts’. Such a blatant instance of institutional ‘artwashing’ now seems to be almost a historical artefact: an encouraging sign, perhaps, of the rapidity with which the climate emergency has become a primary concern among artists, gallerists and museum audiences.

Self-Portrait on Alwyn North (2005), Fionna Carlisle. Courtesy Kilmorack Gallery/the artist; © Fionna Carlisle

While recent headline-grabbing protests by organisations such as Just Stop Oil have used art to generate media spectacle, those protests have notably been directed at governments rather than galleries, many of which have already distanced themselves from the oil industry. Along with the rest of the institutions that make up National Galleries Scotland, the Scottish National Portrait Gallery stopped accepting patronage from fossil fuel companies in 2019, when it ended a long relationship with BP. This followed a similar move by the Tate in 2017, which ended its own BP deal after a six-year campaign by the art collective Liberate Tate. The National Gallery stopped accepting money from Shell in 2018, while the National Portrait Gallery dropped BP as a sponsor in 2022, ending a 30-year partnership. The story is similar across museums in continental Europe and North America, while in Britain the last major holdout remains the British Museum, whose funding arrangement with BP, having apparently lapsed in the summer of 2023, was renewed in December. The new deal amounts to a total of £50 million over ten years – slightly less than half of one per cent of the annual profit reported by the company in 2023 alone. It remains to be seen whether the inevitable protests against this decision will force a rethink. Yet those who continue to oppose fossil fuel sponsorship in the arts might take heart from an observation made by Connolly in 1934. ‘The disapproval of people of taste,’ he wrote, ‘is the pea in the mattress of the spoilt princess of modern big business. She may appear to snore as comfortably as ever, but sooner or later she groans in her sleep.’

From the May 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.