In 1905, the American industrialist and collector Henry Clay Frick acquired a portrait by Titian of Pietro Aretino, the 16th-century writer and libertine. Since the Frick Collection opened in 1935, it has been one of the museum’s masterpieces and has hung in the Living Hall, to the right of Giovanni Bellini’s Saint Francis in the Desert.

Aretino moved to Venice in 1527 after a series of adventures. In 1524, when he was living in Rome, he wrote 16 sonetti lussuriosi (lustful sonnets) to accompany the erotic images designed by Giulio Romano and engraved by Marcantonio Raimondi, known as I modi (the ‘ways’ or ‘positions’). As a result of their publication, Romano left Rome, Raimondi earned some jail time and Aretino made a number of enemies within the papal Curia. On the night of 28 July 1525, while riding through the city, he was stabbed twice in the chest and multiple times in the hands. After this unsuccessful assassination attempt, Aretino left Rome in October, in the service of the condottiero Giovanni de’ Medici ‘dalle Bande Nere’, whose death in 1526 prompted him to move to the court of Federico Gonzaga in Mantua. Heartbroken after affairs with Isabella Sforza and with a young boy, Aretino left for Venice, where he was to spend the rest of his life. During the 30 years that Aretino lived in the city, Titian became one of his closest friends. Aretino wrote extensively about the painter’s work; Titian painted Aretino several times.

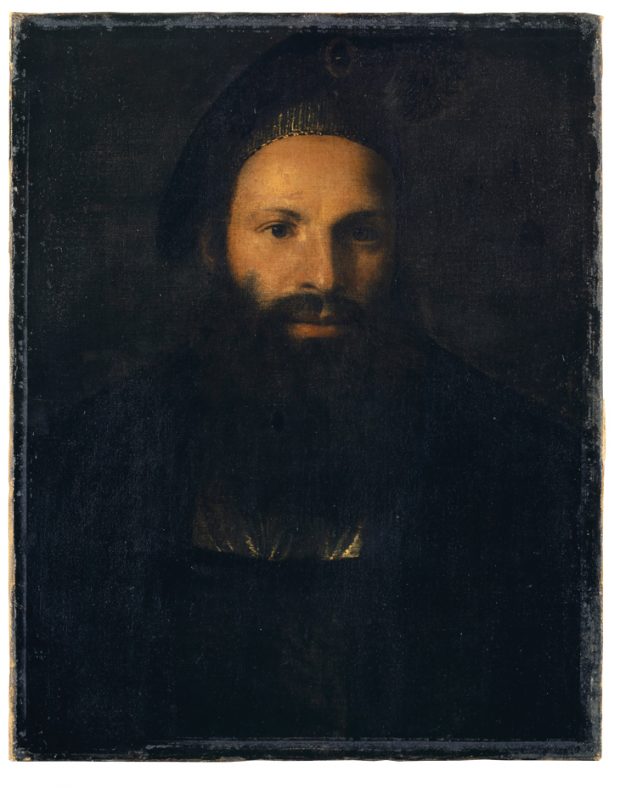

Portrait of Pietro Aretino (c. 1537), Titian. The Frick Collection, New York.

The Frick portrait was painted for Aretino’s publisher Francesco Marcolini in around 1537 and documented for more than 200 years in the Chigi collection in Rome. Aretino was portrayed many times by contemporaries including Sebastiano del Piombo, Moretto, Francesco Salviati and Tintoretto, among others. After the portrait for Marcolini, Titian painted Aretino again, in 1545, for Cosimo I de’ Medici (son of Aretino’s former patron). Describing the painting to the duke, Aretino wrote that it ‘certainly breathes, its wrists pulse and move the spirit as I do in life’, but to Titian he complained that he found it ‘somewhat sketched rather than finished’ (più tosto abbozzato che fornito). Remaining in the Medici collection, this portrait is now on display at Palazzo Pitti.

However, we know that Titian’s first portrait of Aretino was painted soon after the writer arrived in Venice, in 1527. On 22 June of that year, Titian wrote to Federico Gonzaga about the portrait of Aretino that he was sending him; it was most likely a gift made with the intention of encouraging further patronage from the marquess of Mantua. In the early 17th century, Carlo Ridolfi described the painting thus: ‘He [Titian] portrayed him [Aretino] with a black cap on his head embroidered with plumed tassels held by a gold medal with the motto Fides, which had been given to him by the duke of Mantua, and in his right hand he held a crown of laurel.’ It has been considered lost since then by most scholars.

Only three years after Frick acquired his Titian portrait, in the summer of 1908, Louise Bachofen-Burckhardt, the widow of the Swiss anthropologist and sociologist Johann Jakob Bachofen, purchased in Berlin a portrait of Aretino, attributed to Sebastiano del Piombo, for 10,000 francs, on the advice of Wilhelm von Bode. The painting was restored by Aloys Hauser and reached its new owner in Basel in November that year. Bachofen-Burckhardt, who inherited her husband’s collection after his death in 1887, was assembling a large group of paintings and created a foundation in memory of her husband, with the intention of donating it to the Kunstmuseum Basel. After her death in 1920, more than 300 paintings from the foundation entered the collection of the museum, including the portrait of Aretino. (The Kunstmuseum Basel will hold an exhibition celebrating Bachofen-Burckhardt’s collecting and the centenary of the gift from 26 October–29 March 2020.)

Portrait of Pietro Aretino (1527), here attributed to Titian. Kunstmuseum Basel

The portrait of Aretino in Basel has had several different attributions since then. It was published in 1914 by Paul Ganz as a Sebastiano, an attribution endorsed by Bernard Berenson and Rodolfo Pallucchini, and by most early guidebooks to the museum in Basel. In 1943, György Gombosi linked the painting to the documented, but lost, portrait of Aretino by Moretto, a suggestion accepted by Berenson and later by Harold Wethey. Most scholars have, however, questioned both attributions. Today the website of the Kunstmuseum lists the painting as by a ‘Venetian master, 16th Century’ and concludes that ‘the question of attribution remains unresolved’. More recently, art historians such as Mauro Natale, Barbara Agosti and Raymond B. Waddington have described the portrait as an anonymous work. The canvas, untouched since Hauser, is in storage in Basel. After it was shown in ‘Art vénitien en Suisse et au Liechtenstein’, a show curated by Mauro Natale in Pfäffikon and Geneva in 1978, it has not been seen or studied by scholars of Italian art and the judgment around the portrait has been based mostly on black-and-white photographs.

In 1939, however, in an article in the Burlington Magazine, Wilhelm Suida attributed the painting to Titian, identifying it as the lost work created in 1527 for Federico Gonzaga. Subsequent scholars, without seeing the painting itself, rejected his view. Reviewing the Swiss exhibition in Paragone in 1979, however, Carlo Volpe returned to Suida’s attribution to Titian. He pointed out the painting’s poor condition and the fact that the canvas has probably been cut down. Both Suida’s and Volpe’s attributions have, somewhat surprisingly, been ignored by subsequent art historians. Waddington’s monograph of 2018 – the first as far as I know to publish a photograph in colour of the portrait – presents the work as by an ‘artist unknown’, but concedes that it may be ‘possibly a copy of Titian’s lost portrait of 1527 for Federico Gonzaga’ and ‘may derive from Titian’s lost portrait, although it lacks the flourished laurel crown’.

I have long been convinced that Suida and Volpe were right. In June, I examined the portrait in the Kunstmuseum Basel with the curators Bodo Brinkmann and Gabriel Dette. The museum was generous enough to carry out technical analysis – X-radiographs and infrared reflectography – at my request. The results prove that an important Titian has been hiding in plain sight in museum storage. The painting’s surface is rubbed and obscured by subsequent repaints and layers of discoloured varnishes, but despite its poor condition, the quality of the portrait is exceptional. Aretino is wearing a scuffiotto: a type of hat he was keen on, as we know he ordered two of them from Mantua in 1524. The similarity between the portrait and Marcantonio Raimondi’s engraving of Aretino from the early 1520s is undeniable, as noted by Suida. The areas of light and shadow, the construction of the eyes and of the lips are all consistent with Titian’s work from the late 1520s, and particularly close to his portrait of Federico Gonzaga in the Prado. The lack of cusping on all sides of the canvas and its current proportions prove that the painting in Basel is a fragment, cut on all sides. That is why the hand and laurel crown are missing. The badge in the scuffiotto is also heavily repainted, and it is impossible to ascertain what the impresa on it is, or if there are any inscriptions on it. It is highly likely that the canvas in storage in Basel is indeed a fragment of the portrait sent to Federico Gonzaga. A full restoration is the rational next step to demonstrate once and for all the superb quality of the painting and its paternity by Titian.

The Kunstmuseum Basel’s portrait of Pietro Aretino (left); The Frick’s portrait of Aretino (right)

From the September 2019 issue of Apollo. Preview the current issue and subscribe here.